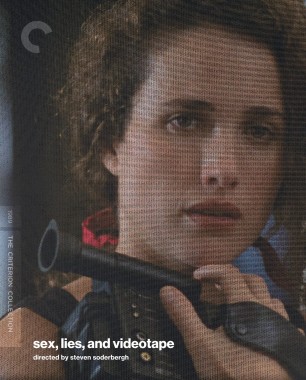

sex, lies, and videotape: Some Kind of Skin Flick

Without doubt, Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape struck a nerve when it was released in 1989. Astonishingly, it still does today. Among the most storied of American independent films, it debuted at the U.S. Film Festival (soon to be renamed the Sundance Film Festival) and immediately transformed that earnest refuge from Hollywood commercialism into a magnet for Los Angeles power brokers looking for fresh talent. Soderbergh’s first narrative feature went on to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes and earned as much as $100 million worldwide on its initial theatrical release. It had cost a mere $1.2 million to make.

Among the secrets of its success: sex, lies, and videotape is a hotbed of contradictions. The very subjects announced by the title so often lead to conflict: who has not been pulled in opposing directions by sex, to the extent that lying to oneself and others becomes, on occasion, a necessary condition? And when portable video cameras became ubiquitous, they threatened to bring that muddle of desire and guilt into the open, with potential ramifications both positive and negative for all concerned. But let’s begin with the most enveloping contradiction: the fantasies evoked by the tawdry tabloid connotations of the title versus the experience of the film itself, which has the sun-drenched beauty of an eighties House & Garden spread. The setting is Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in summer, and there are plants everywhere, inside and out. Shot on 35 mm film, often making use of the light that floods high-ceilinged rooms through large windows, sex, lies, and videotape is not only pleasing to the eye, it also has an extraordinary tactility.