King of Kings: Showman of Piety

In the classical Hollywood era, it was axiomatic that the public didn’t give a damn about directors. For all the notice taken of the profession by gossip columnists, fan magazine writers, and studio flacks, movies could have grown on trees or sprung Athena-like from the heads of the only talent that mattered—the stars. The reasons for this indifference aren’t hard to figure. Directors tended to be stout, homely middle-aged men—not exactly the stuff that dreams were made of. Besides, what they did sounded too much like work to your ordinary filmgoer. It would require that seismic shift in taste known as auteurism to confer on the director a measure of the idolatry reserved for stars. In the meantime, there were a handful of rule-proving exceptions. As the legendary founding father of Hollywood, D.W. Griffith trailed clouds of glory well into the 1920s, though his Victorian hearts-and-flowers sensibility rendered him a magnificent dinosaur. Erich von Stroheim and later Orson Welles enacted the romantic tragedy of the Promethean genius struck down by angry gods (or at any rate the front office) for heroic overreaching. Film-makers of less imperial dimensions might stamp their names on mass consciousness if they specialized. Ernst Lubitsch with his celebrated touch, Frank Capra with his sentimental populist corn, and the ultimate brand label, Alfred Hitchcock—each advertised a line of entertainment so distinctive as to earn that rarest of tributes, above-the-title billing.

Then there was Cecil B. DeMille, who basked in the spotlight continuously from the early silent period to the age of CinemaScope and stereophonic sound. He may not have been the finest auteur in screen history—indeed, highbrows held him beneath contempt as the living emblem of vulgar Hollywood materialism and its cynical appeal to the lowest common denominator. Given the mastadonic costume pageants on which DeMille sealed his fame, it isn’t surprising that he should have become chief whipping boy for intellectuals. Where a Murnau or an Eisenstein disclosed startling new horizons for cinema as an art form, DeMille returned it to the most primitive bread-and-circuses spectacle. Yet the very mirth he inspired among the discriminating was an inverse tribute to his unshakable cultural dominance and longevity with the big audience. For three generations of movie fans, DeMille embodied a majestic cartoon archetype: the director as warlord, as field marshal, as megaphone-barking autocrat. Incredible but true—DeMille sported high boots, riding breeches, even twin pearl-handled revolvers (a necessary precaution against the lions and tigers that were de rigueur for pagan orgy scenes). The Prussian affectations go back to Erich von Stroheim, who legitimated them through his iron-willed creative intransigence and self-belief. In DeMille, they were total flimflam—the chintzy regalia assumed by a carnival spieler.

The two are cruelly juxtaposed in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), where von Stroheim plays his own surrogate, Max von Mayerling, washed-up wunderkind, nursing the delusions of the equally superannuated Norma Desmond. DeMille plays DeMille, a cool pragmatist who has stayed afloat in the reconstituted Hollywood and gazes with pity on these fossils, his erstwhile comrades. If he alone survived the Götterdämmerung, it was by keeping a permanent finger to the wind. Few people remember that DeMille was once judged an innovator on a par with Griffith. The French avant-garde swooned over his 1915 melodrama The Cheat for its bold chiaroscuro lighting and shimmering Orientalist décor—not to mention the voluptuous sadomasochism of the fabled moment when a red-hot brand sinks into the heroine’s alabaster flesh. DeMille’s 1918 The Whispering Chorus is a moody expressionist tale of guilt and redemption that anticipates film noir by nearly thirty years. The commercial failure of this cherished project seems to have ended his flirtation with art and the metropolitan elite who valued it. Thereafter, he emerged as sovereign fantasist of the silent majority.

In Male and Female (1919) and Manslaughter (1922), he introduced the gambit of the historical flashback—whereby dissolute flappers were apprised of their certain comeuppance through a tableau vivant itemizing parallel excesses in Babylon or Ancient Rome. Sophisticates howled at the rubbernecking moralism and its grotesque lack of proportion; but desperate times called for desperate remedies. Busybody reformers were applying heat to the movie colony after a series of high-profile scandals. So it came to pass that DeMille looked and found God waiting in the wings. The Ten Commandments (1923) was a behemoth Sunday school diptych contrasting the bestowal of Mosaic Law with its modern-day infringement. Born again—not least at the box office—he logically progressed to the New Testament.

The story is often told against DeMille that he arranged for Mass to be said each morning during the production of The King of Kings and obliged cast members to sign an affidavit swearing their Christian rectitude. The point is usually to mock the Pharisaical piety of a slick operator; but in truth, no filmmaker was more sincere. DeMille just couldn’t perceive any antipathy between religion and well-oiled ballyhoo. Here as elsewhere, he loyally reflected his constituency. It was, after all, the epoch of Aimee Semple McPherson, whose tub-thumping evangelism never ruled out the fast buck or a private life befitting The National Enquirer. DeMille recognized and revered a profound quality in the American soul—its ability to leap over every contradiction through an invincible sense of its own righteousness. The King of Kings was his first freestanding biblical epic—since even he appreciated how interlarding the Passion with scenes of clip joints and riotous Charlestons might represent a failure in tact. But gravitas didn’t deter him from opening the movie on a whore. As revamped by DeMille, Mary Magdalene is admittedly an upscale tart. Slinking around in her jewel-encrusted tiara and glittery breastplates, pet leopard at hand for lascivious stroking, she testily inquires as to the whereabouts of Judas Iscariot, foppish young blue blood, rising politico, and her lover. Embroidery is too mild a word for DeMille’s characteristic throttling of the simplest facts. But though P.T. Barnum’s immortal adage “suckers” comes to mind, this kitschy farrago achieves its object of galvanizing the attention. And the concept of de trop being alien to a visionary hustler, there follows the sublime title card: “Harness my zebras—gift of the Nubian King! This Carpenter shall learn that He cannot hold a man from Mary Magdalene!”

The harlot’s instant reform by Jesus typifies that reckless miscegenation of the sacred and the profane that DeMille termed showmanship. One stern glance from the Messiah and the Seven Deadly Sins throw in the towel—each vacating Mary’s body in turn, a complete séance of leering, writhing phantasms. The multiple exposure is sensationally effective, but it’s more than a conjuror’s trick. DeMille understood that his audience wanted literal, physical miracles. As a religious film, The King of Kings is in a whole different galaxy than, say, Robert Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest (1951), where God’s presence remains ineffable and inscrutable, eliciting an act of faith from the viewer as much as from the tormented hero. (If DeMille’s peculiar blend of decadence, sermonizing, and impresarial cunning evokes the work of any art-house master, it’s that of Federico Fellini.) The King of Kings adheres to Hollywood’s strict fundamentalism in that photographic legerdemain doubles for the clear manifestation of divine will. Christ initially enters the narrative as an image swimming up in the restored optic of a blind girl—the supernatural cure authenticated by cinema’s own infinite capacity to see. With equally pat symbolism, ordinary black-and-white film stock connotes the fallen state of humanity before the Resurrection. When Christ is risen and the Holy Covenant redeemed, however, the film medium itself rejoices—in a four-minute blaze of early two-strip Technicolor.

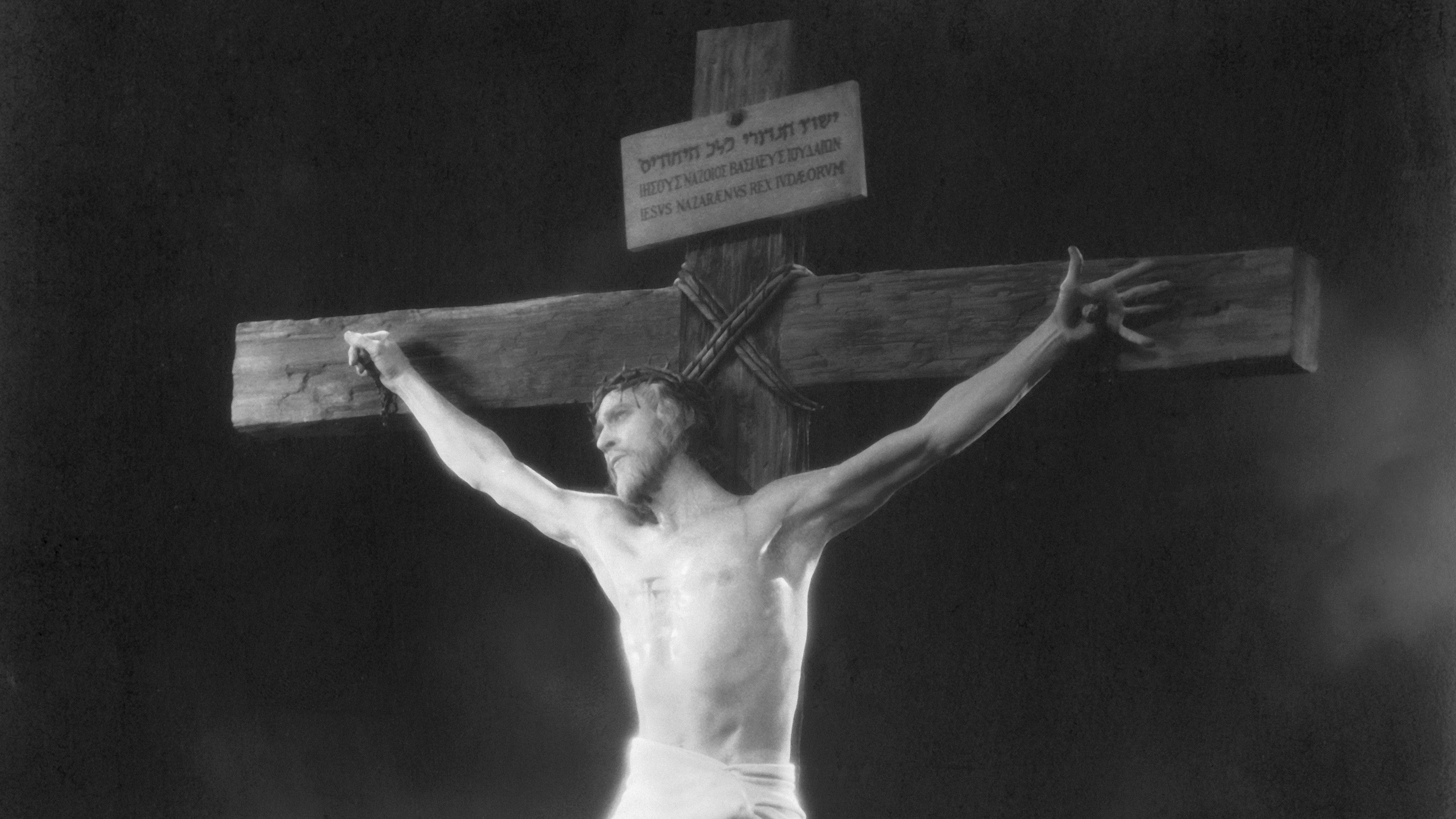

But the great showstopper is inevitably the Crucifixion. When Our Lord breathes his last, the inkiest of storm clouds descend, lightning blazes, and gigantic fissures in the earth swallow up half of Central Casting. It’s a stupendous exhibition by any standard, though you can practically smell the sawdust and greasepaint. DeMille’s fustian mise-en-scène harks back to the hyperrealistic machinery of nineteenth-century stagecraft, with its rolling panoramas and artfully counterfeited natural disasters. There’s also a resemblance to popular genre painting in the isolation of choice vignettes—the Blessed Virgin shutting out the sound of the nails penetrating, a woman blasphemously eating peanuts (perhaps revealing the director’s secret scorn for the fickle mob). As Jesus, H.B. Warner is appropriately flawless. Call it proto-Method acting if you will, but he comes through with a performance of absolute iconographic conviction. This isn’t the struggling, humanized deity in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) or Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). And he certainly isn’t the flagellated, maimed, blood-spattered figure of Mel Gibson’s recent, controversial The Passion of the Christ, which might be called The Gospel According to the Marquis de Sade. DeMille’s Christ is the serenely glowing effigy of stained-glass windows, plaster figurines, and a million dog-eared holy pictures. Despite the baloney (or because of it), The King of Kings captures the fervor of naïve devotion. On that level, the movie is a genuinely uplifting experience.

Having once hit the mother lode, DeMille never budged. Such valedictory blockbusters as Samson and Delilah (1949) and the widescreen remake of The Ten Commandments (1956) display the same stilted, archaic technique as the silent films. DeMille didn’t need to change, for he knew that his hokum incarnated the eternal and irresistible essence of show business.