Mala Noche: Other Love

“They all say that I’m ‘openly gay.’ But they put that in as a little political footnote . . . They don’t say anything about gayness. They just say, ‘He’s openly gay.’ They relate it a little bit to something, but they just get through with that bit.” —Gus Van Sant on his press coverage, in an interview by Gary Indiana in the Village Voice, October 1, 1991

You could say that Mala Noche, Gus Van Sant’s first feature, completed in 1985, is openly gay. So open in its gayness, in fact, that the narrative’s driving force—blind, unembarrassed homosexual lust—is established in a matter of seconds. Before we’ve quite found our bearings (the image is dark, the framing tight), Walt (Tim Streeter), a stubbled, sleepy-eyed guy behind the counter of a scuzzy liquor store, delivers a deadpan stoner voice-over paean to the teenage cutie who’s just sauntered in: “I want to drink this Mexican boy, Johnny Alonzo, from L.A. near Riverside. He makes my heart throb—thumpety, bum, bum, bum, bum, bum—when I see him.”

Their faces barely emerged from shadow, illuminated only by a hanging lamp, hunter and prey size each other up. Walt, a good-looking thirtyish fellow with an easy manner, doesn’t hold back: “Hey, I want to be your friend . . . su amigo?” Johnny (Doug Cooeyate), an illegal alien who rode the rails north to Portland, Oregon, in search of work, plays it cool. But Walt, smattering his come-ons with broken Spanish, is the persistent type. Later, after confiding in a friend—“I’m in love with this boy . . . I have to show him that I’m gay for him”—Walt finds Johnny at a video arcade, feeds him and his friends a home-cooked meal, lets him drive his car, and at evening’s end, professes his love and offers him fifteen bucks for sex.

The deal falls through, so Walt, settling for next best, spends the night with one of Johnny’s buddies, Roberto (Ray Monge), a.k.a. Pepper, who’s been locked out of the boys’ fleabag flophouse and who appears to be gay—or, in any case, appears to like men well enough if he’s on top. Notwithstanding a quick detour to the medicine cabinet to grab a jar of Vaseline, the sex scene is a model of discreet eroticism, not to mention a prime early example of Van Sant’s gift for intuitive montage: hands on naked flesh, a smile in the dark, and an obscuring blur of close-ups, set to the suggestive clank and whistle of a passing train. In his morning-after soliloquy, sounding at once self-pitying and elated, Walt acknowledges Pepper’s surrogate status: “That’s about as close to Johnny as I’ll ever get.” He also notices that the ten-dollar bill in his trouser pocket is missing.

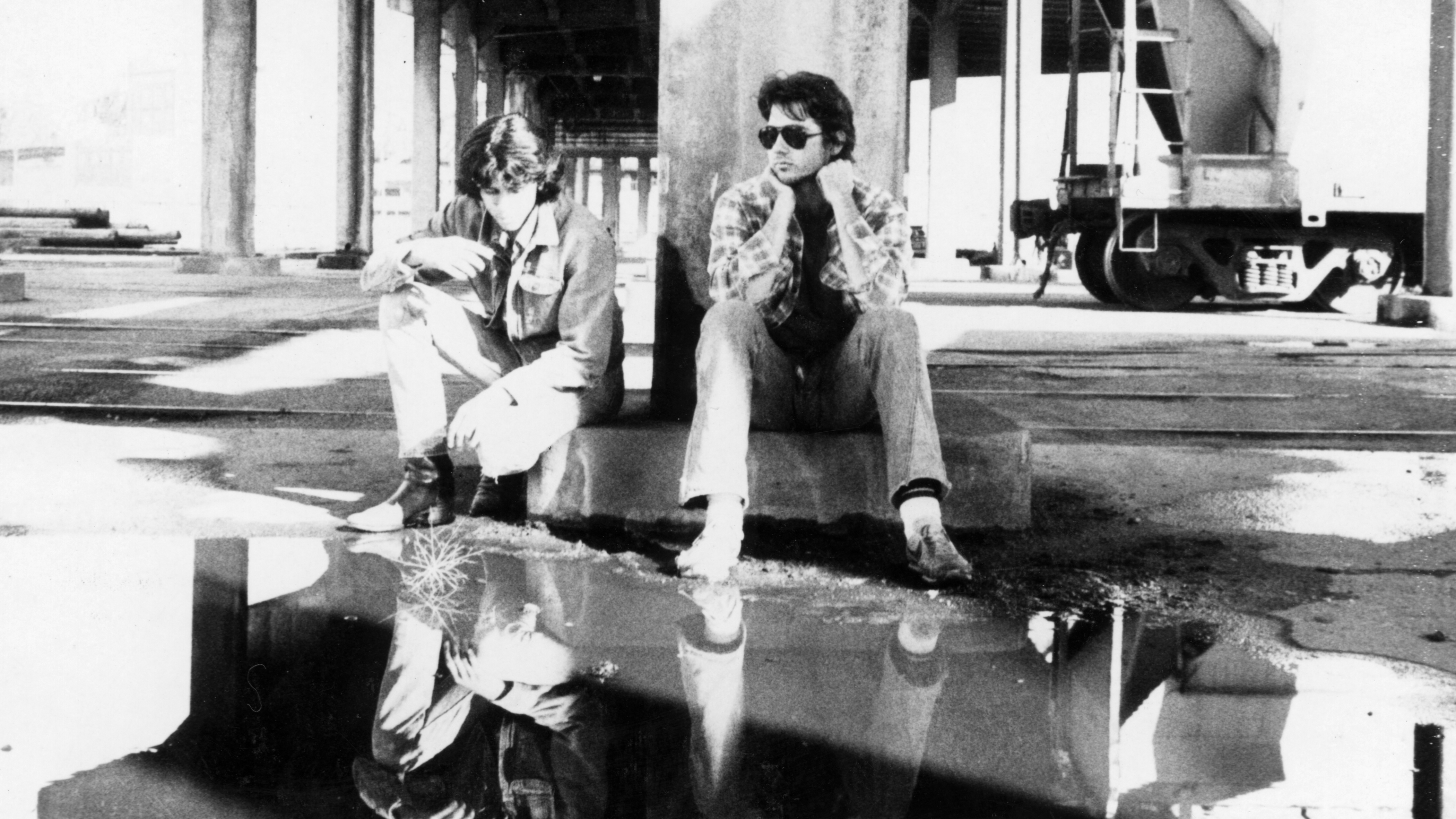

An unabashedly romantic blast of beatnik lyricism, filmed in the inkiest black-and-white chiaroscuro and soundtracked to languid alt-country arpeggios, Mala Noche nevertheless maintains an unsentimental clarity when it comes to its central relationships. Walt, Johnny, and Pepper form a triangle of thwarted and displaced desire, a diagram of mutual need and exploitation. Each one plays his designated role in the social and sexual economy. Practically every interaction is a transaction. (Walt and Johnny’s first meeting, at the store, is punctuated by close-ups of the almighty greenback and a cash register with a Stars and Stripes sticker.)

Shot in 16 mm, on twenty-five thousand dollars of the director’s own money, Mala Noche is commonly regarded as one of the great DIY triumphs of its day. After graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in the mid-seventies, Van Sant put in a few demoralizing years in Hollywood (and a few lucrative ones on Madison Avenue) but retained ties with the artistic community in Portland, where he grew up. It was while working as a soundman on a Portland indie production, Penny Allen’s Property, that he met Walt Curtis, a local poet who was acting in the film. He read Curtis’s semiautobiographical chapbook Mala Noche and, he says, kept it hidden under his bed for years before it occurred to him to turn it into a film.

Van Sant’s Mala Noche is, on the one hand, very much a product of its era. American independent film of the eighties was notable for its handful of iconoclastic, often region-specific voices (including Van Sant, Jim Jarmusch, John Sayles, John Waters, and Spike Lee). This was before the homogenizing waves of faddists and imitators wrought by the nineties Sundance boom (incidentally, Sundance, then known as the U.S. Film Festival, rejected Mala Noche in 1986).

But seen today, the film also seems far ahead of its time, in large part because it so blithely bypasses the identity politics and representational burdens of “gay cinema.” It has been retroactively anointed a forerunner of the so-called New Queer Cinema that emerged in the early nineties. But Van Sant in general, and Mala Noche especially, stand apart from that movement’s initial salvo (and, needless to say, from the gaysploitation dreck that took over as the decade wore on), less cerebral than Todd Haynes and less sloganeering than Gregg Araki.

In other words, Mala Noche is so openly gay that it may be more useful to think of it as incidentally gay; Van Sant has more universal—and more particular—concerns in mind than the simple fact of Walt’s sexual orientation. The film is an anatomy of desire, and a good deal tougher and thornier than its air of pensive distraction might suggest. Much of the voice-over and dialogue is lifted from Curtis’s story, which Van Sant adapted shrewdly, culling the most resonant lines and lending rhythm and form where there was previously sub-Burroughsian gush. The film takes shape from the schizoid swings of mad infatuation—-panicked desperation in the loved one’s absence, manic euphoria in his presence. There’s also a generosity in the movie that’s largely absent in the book; Van Sant, one of the least judgmental of contemporary American filmmakers, paints a more flattering picture of Curtis than Curtis does himself.

A connoisseur of exotic jailbait, Walt, as Van Sant has acknowledged, is “certainly not a positive gay character.” The sheer directness of his ardor is charming but also unnerving. His racial fetishism often coincides with a casual racism (when he’s mad at Johnny or Pepper, he’s liable to make generalizations about “the Mexicans”). The Walt-Johnny relationship is far from straightforward—if anything, it’s one complicating factor after another—and while Walt ignores the obvious minefields, Van Sant is far from oblivious.

Johnny doesn’t just fill the role of the eroticized Other—he’s about as Other as it gets, separated from Walt by age, ethnicity, and language, as well as economic, social, and legal standing. Without exempting Walt’s adoration from skeptical scrutiny, Van Sant liberates it from the unhelpful dead end of moral judgment. He plays the lopsided amour fou for dry tragicomedy, as he would do again in My Own Private Idaho (1991). But he also matter-of-factly poses the prickly questions: What happens when the unstoppable force of desire collides with the unmovable realities of race and class? In a relationship premised on various imbalances of power (as are, after all, so many), why wouldn’t each party make the most of his advantage? (And isn’t imbalance of power the basis for a certain kind of sexual attraction?) Does being exploited justify being an exploiter?

Walt, who also works part-time as a janitor, doesn’t have much, but it’s in his nature to be giving, and as he cannot help pointing out, he’s in a position to offer these impoverished migrant workers a free meal, a ride in his car, a sleeping bag for the night. (“A gringo like me has an easy life, a privileged life,” he muses.) Johnny, aloof as he is, knows to reciprocate just enough, to be more receptive of Walt’s unsolicited attention when he wants something; this dance of approach and avoidance is literalized in one of the film’s driving scenes, ostensibly mischievous but fraught with hostility, in which Johnny and Pepper, having taken over Walt’s car, repeatedly pull away from him as he struggles to catch up. Mockable as he is to the boys—Johnny tauntingly calls him a puto (faggot)—Walt comes to assume a quasi-parental role, always good for a driving lesson or a stern admonishment or a sickbed visit.

Is it ironic or merely logical that Van Sant began his career—one distinguished by a parade of young and beautiful boys—with, if not a defense, then at least a sympathetic portrait of an age-inappropriate crush? He once described Curtis’s story as “Death in Venice on Skid Row,” invoking the granddaddy of all chicken-hawk fables. But Walt is hardly a pathetic, closeted Aschenbach figure. As played by Streeter, who delivers what should have been a star-making performance (but who barely acted again), Walt is likable, basically decent, relatively well-adjusted, confident in his own skin, ambling down the main drag and cheerfully schmoozing passersby like the mayor of the neighborhood. He experiences his unrequited love not as abject humiliation but as a form of addiction. The pain and drama are self-fueling and even perversely ennobling—as illustrated in a fantasized scene in which Walt bursts into the boys’ room, beatifically backlit, and throws himself at Johnny’s feet like a fallen saint, seeking redemption through martyrdom.

This fully formed debut contains Van Sant’s pet themes (alienated youth, conflicted male relationships) and the traits of his quintessential hero (haunted, sincere, painfully sensitive, but not entirely humorless). It also features many of his poetic signatures—not just those famous time-lapsed clouds but the more ingrained gestures that happen on the level of film syntax: a dreamy elasticity of time, a jazzy deployment of repetition and punctuation.

Van Sant’s career has had at least three phases—the Pacific Northwest films, the Hollywood dalliances, the born-again formalism of his recent “death trilogy”—and is commonly discussed in terms of its wayward detours. But his résumé indicates not so much capriciousness as a willingness to both react to and build on what came before. His twelfth and most recent feature, the cosmic, Portland-set coming-of-age tale Paranoid Park (2007), may be his supreme achievement, refining and synthesizing the avant-garde gambits of Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003), and Last Days (2005) to the point where they seem like second nature—indeed like a direct outgrowth of Mala Noche’s jagged, deeply felt poetry. In the context of this continually surprising director’s still evolving career, his indelible first film looks ever more central.