The Virgin Suicides: “They Hadn’t Heard Us Calling”

In the final moments of Sofia Coppola’s 2003 movie Lost in Translation, the quixotic romantic connection between Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) and Bob (Bill Murray) culminates on a crowded Tokyo street not with a kiss—though there is one—but with a whisper.

Leaning close, Bob says something in Charlotte’s ear. Something, but we don’t know what. Coppola, who also wrote the screenplay, leaves it up to us, permitting us to project our own private fantasies onto those muffled words. The private, unknown, ungraspable quality of the final exchange—after we’ve been privy to such intimacy between the two characters—gives the closing a greater poignancy: it’s a bittersweet reminder that something has ended.

If you consider that moment in light of Coppola’s luminous debut film, The Virgin Suicides (1999), an adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’s celebrated 1993 novel, its significance deepens. In the hazy, dreamy, poisonous world of The Virgin Suicides, language is limiting, even imprisoning, while greater, more profound truths lie beyond narration, in the visual, in the experiential, the imaginative.

“With a book like this, no one should really play the characters,” Eugenides once mused when asked about the adaptation, “because the girls are seen at such a distance. They’re created by the intention of the observer, and there are so many points of view that they don’t really exist as an exact entity . . . I tried to think of the girls as a shape-shifting entity with many different heads. Like a Hydra, but not monstrous. A nice Hydra.”

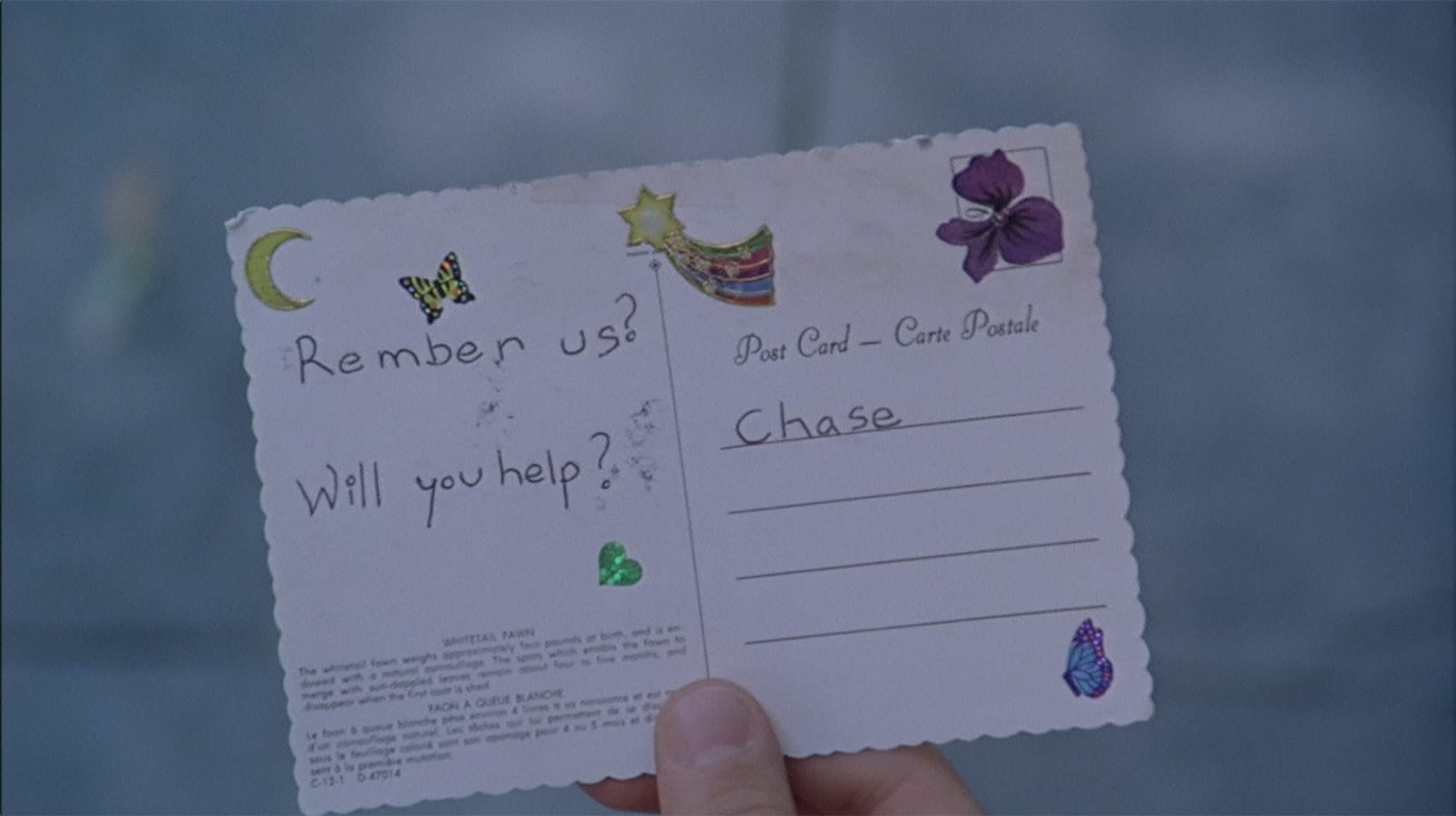

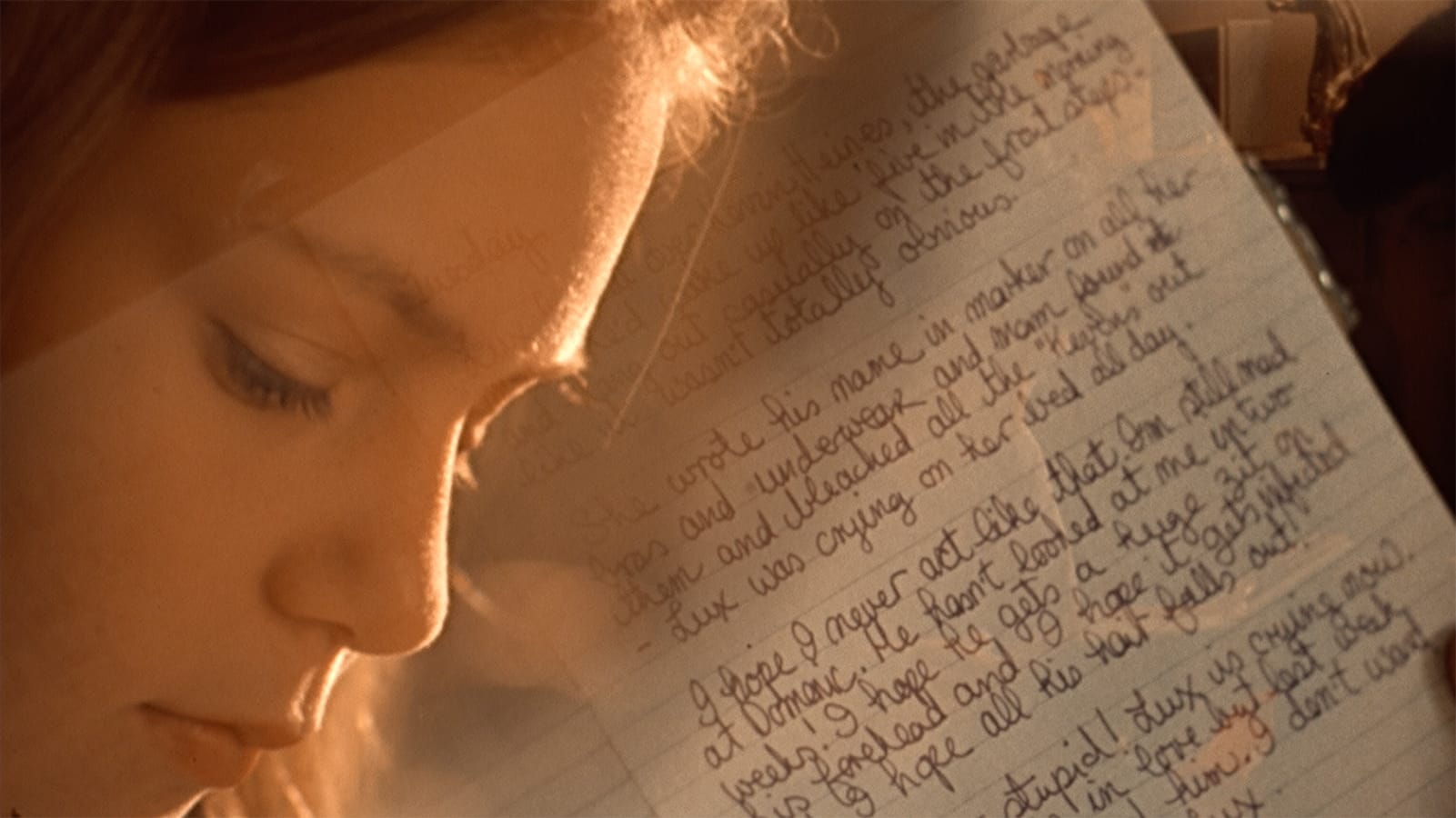

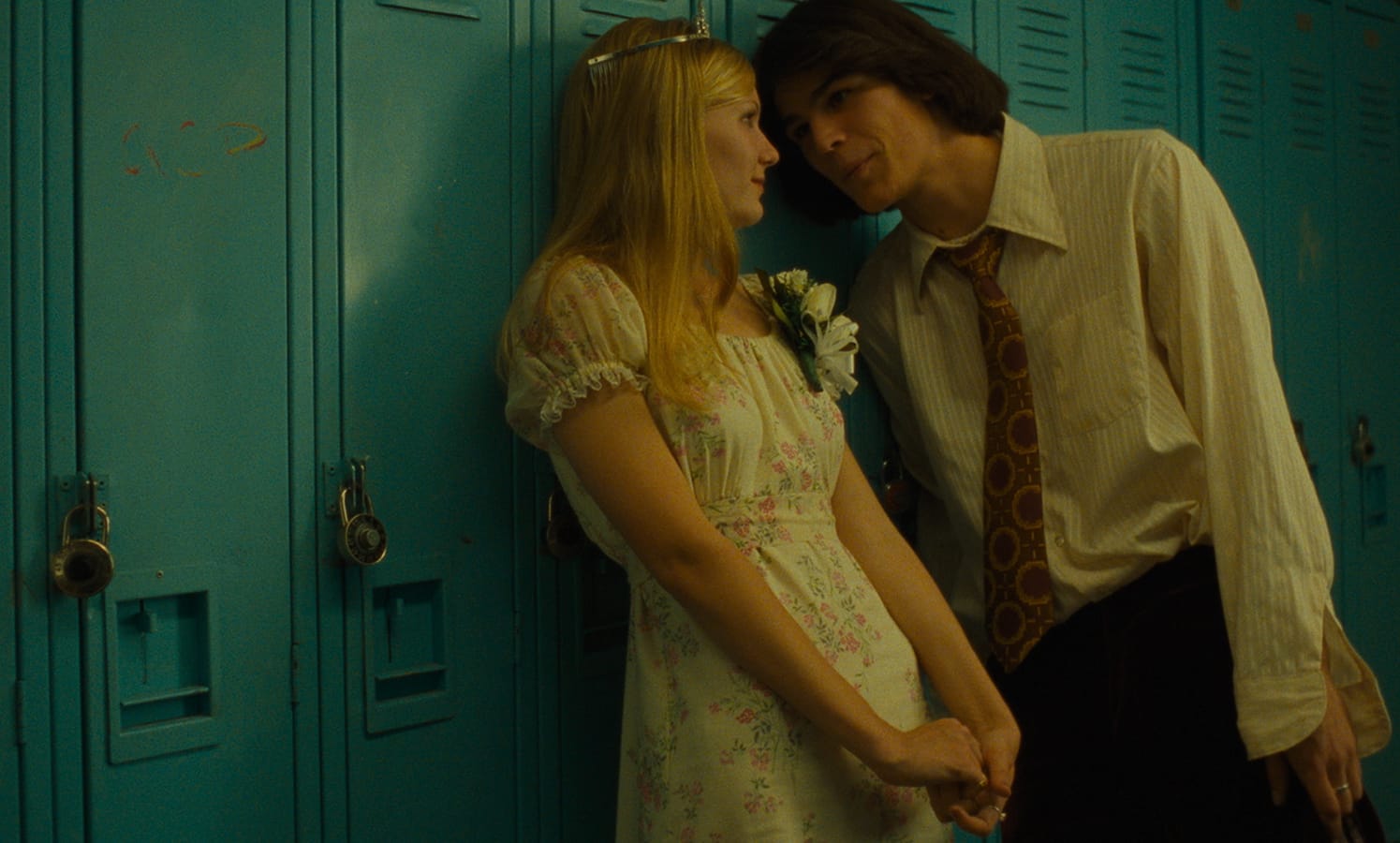

Indeed, Eugenides’s novel explores the many ways boys try, and fail, to understand girls—or, more largely, an essential femininity that seems forever just beyond their grasp. The story is told through a kind of collective narrator—a group of men, now approaching middle age, who are haunted by an episode from their youth in suburban Michigan during the 1970s, when the glamorous Lisbon sisters, a source of captivation for the boys, took their own lives. As the narrator attempts to make sense of the sisters’ lives and deaths, we see unfurl a glorious romantic tapestry stitched together from the boys’ imaginations, speculations, private fantasies. Underlying Eugenides’s tale is the understanding that their knowledge is only ever partial and that, ultimately, rather than constructing a history of the Lisbon girls, they are excavating their own histories, and the things lost between their wide-eyed adolescence and their sad, “soft-bellied” adulthood.

Coppola has said that, for her, The Virgin Suicides is about “how deeply people can affect you, and how little images can get the biggest importance, and never go away” (emphasis mine). Restricting the novel’s fulsome, extravagant, word-full storytelling to the voice-over (provided by Giovanni Ribisi), she infuses her film with images—impressionistic, unnarrated peeks into the sisters’ world on its own terms. In so doing, she exposes the tragic chasm between the narrator’s assertions about the sisters (what they represent, how they might be “diagnosed”) and the sisters’ actual private experience. And, while the majority of the movie consists of following the boys’ gaze, Coppola is determined, too, to show us what they can’t see, what they misunderstand, what they simply miss. By the closing shots—following the girls’ desperate final effort to escape their imprisonment at the hands of their parents (Kathleen Turner and James Woods)—the gulf between what we hear and what we’ve seen feels immense, impassable.

“If the novel and the movie’s structure are about boys telling, Coppola’s visual strategy is about girls showing.”