Pierrot le fou: Self-Portrait in a Shattered Lens

In February 1964, while shooting Band of Outsiders, Jean-Luc Godard announced his plans for a film based on a crime novel, Obsession, by the American writer Lionel White (translated into French as Le démon d’onze heures—literally, “The Eleven O’Clock Demon”). In an interview that month, Godard described it as “the story of a guy who leaves his family to follow a girl much younger than he is. She is in cahoots with slightly shady people, and it leads to a series of adventures.” Asked who would play the girl, Godard told France-Soir in 1964:

That depends on the age of the man. If I have, as I would like, Richard Burton, I will take my wife, Anna Karina. We would shoot the film in English. If I don’t have Burton, and I take Michel Piccoli, I could no longer have Anna as an actress; she would form with him a too “normal” couple. In that case, I would need a very young girl. I’m thinking of Sylvie Vartan.

Both Burton and Vartan (a nineteen-year-old pop singer) were unavailable, and when financing proved difficult to obtain, Godard asked Jean-Paul Belmondo, whom he had made a star with Breathless, to step in. But Belmondo was, and looked, even younger than Piccoli. So when Godard announced in New York in September 1964, when he was in town for the New York Film Festival, that Karina, his wife, would star alongside Belmondo, he was in fact creating an even more “normal” couple and definitively reorienting the tone of the film, as he subsequently explained in Cahiers du cinéma: “In the end the whole thing was changed by the casting of Anna and Belmondo. I thought about You Only Live Once, and instead of the Lolita or La chienne kind of couple, I wanted to tell the story of the last romantic couple, the last descendants of La nouvelle Héloïse, Werther, and Hermann and Dorothea.”

The casting of a worldly actress in her mid-twenties and a handsome, vigorous leading man just over thirty did change the project—but not nearly as much as did the personal significance with which Godard invested the story. White’s novel, as its title suggested, was a story of obsessive desire—specifically, that of a middle-aged advertising man and failed writer for a teenage girl, his children’s babysitter. This girl has underworld connections and a feral aptitude for deception and manipulation; after he leaves his family for her, gets caught up with her in a murder, and goes on the lam with her, she uses, betrays, and abandons him. Desperate and humiliated, he catches up to her and kills both her longtime lover (who she had claimed was her brother) and the girl herself. Godard—who had told Belmondo that the film would be “something completely different” from the book—turned the male lead into a failed intellectual who rediscovers his literary ambitions along with his romantic passion. This man, Ferdinand Griffon, begins to fulfill his vast artistic plans when he and the young woman, named Marianne Renoir, take to the road. Marianne has shady connections—to a shadowy and violent group of arms traffickers and political conspirators—but she proves nonetheless, at least for a time, to be Ferdinand’s helpmeet and soul mate in his great artistic project.

Although Godard’s woman uses and betrays the man no less than does White’s, the effect provoked by Godard is even more extreme: in Pierrot le fou, Marianne not only breaks Ferdinand’s heart but also destroys what was to be his life’s work. The romantic exaltation that Godard thought the casting of Karina and Belmondo had substituted for the story of betrayal and depredation turned into an artistic manifesto and a cry of resentment and pain: by the time he shot the film, from May through July 1965, he and Karina had divorced.

*****

For Godard, the long interval that separated the conception of Pierrot le fou from its realization had been a time of aesthetic as well as personal transition. As a result, when he was finally able to make the film, his original ideas about the project proved to be of little use to him. Recalling the shoot, Godard later said: “I remember that when I began Pierrot le fou, one week before, I was completely panicked, I didn’t know what I should do. Based on the book, we had already established all the locations, we had hired the people . . . and I was wondering what we were going to do with it all.”

In his earlier films, Godard had relied on preexisting frameworks to guide his spontaneous invention, whether Hollywood genres (as in Breathless, Band of Outsiders, and Alphaville) or the intellectual modernism of Brecht or Barthes (as in Vivre sa vie and A Married Woman). But by the time he started shooting Pierrot le fou, the film noir conventions underlying it no longer inspired him, and his theoretical references were in a state of flux due to his political anger as the Vietnam War escalated. The result of Godard’s personal, cinematic, and intellectual turmoil was an immediate creation that reached, even for Godard, new heights of spontaneity and lightning invention—and this was largely an effort to compensate for his inability to be methodical even by the casual terms of his own practiced methods. Shortly after completing the film, he told Cahiers du cinéma: “In my other films, when I had a problem, I asked myself what Hitchcock would have done in my place. While making Pierrot, I had the impression that he wouldn’t have known how to answer, other than ‘Work it out for yourself.’” Godard had had trouble working it out. Classic Hollywood forms couldn’t sustain him as they had in his previous film, Alphaville, which depended heavily on the conventions of the secret-agent and science-fiction genres. Not only was his absorption of the entire classical cinema of no help to him, but also his own experience as a filmmaker was of little use. He said that, in making Pierrot le fou, he felt as if he were making his “first film”; he had lost his North Star of cinematic navigation, and was out at sea.

Yet this lack of mooring, this state of doubt and bewilderment, had surprising results. Godard filmed the genre elements of the story with an inert mechanicalness and a conspicuous boredom, which he masked with elaborate editing, insert shots, and voice-over; but in the scenes of Godard’s own making, in which he did not have to connect the narrative dots, he created a free and flamboyant array of images that were filmed with a manifest burst of untrammeled creation. He called the shoot “a kind of happening, but one that was controlled and dominated,” and said of Pierrot le fou, “It is a completely unconscious film.” In making it, Godard gave unusually free vent to his emotions, and those emotions were harrowing ones: Pierrot le fou was an angry accusation against Anna Karina, and a self-pitying keen at how she destroyed him and his work.

After the release of Pierrot le fou, Godard gave the public a skeleton key to it: “The only scenario that I had, the only subject . . . was to convey the sense of what Balthazar Claës was doing in The Unknown Masterpiece.” The Unknown Masterpiece is a novella by Balzac about a painter in seventeenth-century France who has been working alone for a decade on a portrait of a woman that he considers to be not only his masterpiece but an epochal advance in the history of art; he shows it to two artist friends, who find it to be an incomprehensible mess, a blunder and a disaster, and he kills himself. But Balthazar Claës is not a character in that novella (the painter is named Frenhofer); rather, he is the protagonist of another work by Balzac, The Quest of the Absolute. In that novel, an alchemist in single-minded pursuit of the secret of nature brings about his wife’s premature death, his financial ruin, and his public humiliation. The two fictions by Balzac that Godard’s memory had run together unite in Pierrot le fou, a self-portrait of the artist on the verge of pushing a philosophical inquiry into form, or rather formlessness, to an extreme that destroyed not only himself but also his wife.

Exactly as Godard intended, Pierrot le fou reflects appropriately vast, cosmic, quasi-metaphysical artistic dreams of a Balzacian grandeur. Early in the film, Ferdinand sits in his bathtub and reads to his young daughter a passage from the art critic Elie Faure that begins, “Velázquez, past the age of fifty, no longer painted specific objects. He drifted around things like the air, like twilight, catching unawares in the shimmering shadows the nuances of color that he transformed into the invisible core of his silent symphony.” The first scene thus announces Godard’s own search for another kind of cinematic art, one that goes beyond the visual presentation of objects and characters to a higher relation of musical ideas. (It was a project that would take him another decade and a half, many wanderings, false starts, studies, sufferings, and personal transformations to begin to realize.)

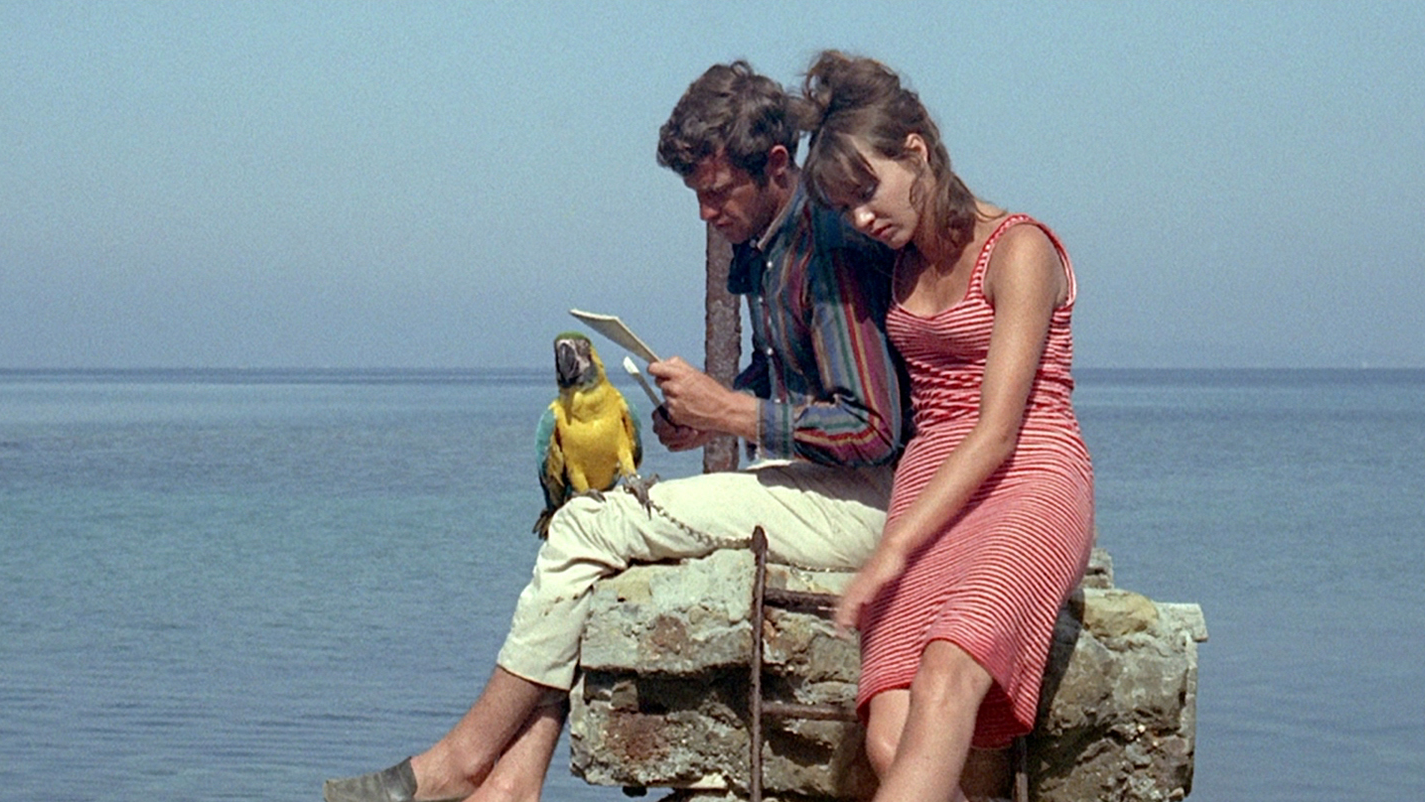

The core of the film is a scene that takes place in the tranquil natural splendor of unspoiled lands in the south of France: Ferdinand and Marianne live off the land, hunting and fishing (albeit cartoonishly—like most of the film’s narrative action), while Ferdinand (sitting with a parrot on his shoulder) begins to keep a journal, which appears in extreme close-up on-screen, and which is in fact in Godard’s handwriting. Among the passages that Ferdinand reads aloud is a description of his ambitious plans for a new form of novel: “Not to write about people’s lives anymore, but only about life—life itself. What lies in between people: space, sound, and color. I’d like to accomplish that. Joyce gave it a try, but it should be possible to do better.” The sequence is the crowning moment in Ferdinand’s dream: the couple will exist together, in isolation at a wild seaside, where the setting and the romantic idyll will inspire Ferdinand’s artistic creation. The glory of nature and a life of shared purpose with a beloved woman are, in Godard’s personal mythology of that period, a natural pair. But soon thereafter—in the famous scene in which Marianne wanders past him and whines repeatedly, “What can I do? I don’t know what to do”—the dream, and the art, are destroyed, by Marianne’s demands and, it turns out, her duplicity. She drags him back to a corrupt civilization and pulls him from his contemplative isolation into a vortex of unwanted action.

*****

Pierrot le fou is filled with art and its attributes, from Marianne’s last name (and some paintings to go with it) to works by Picasso on walls and as insert shots, Ferdinand’s repeated references to Balzac, his lengthy recitation from a novel by Céline (whose first name, Louis-Ferdinand, Marianne likens to his), a reference to Beethoven, the film’s Mondrian-like scheme of primary colors and white, Ferdinand’s daubing of his face with Yves Klein blue—all suggesting that Godard rooted his film in a high artistic and literary tradition that transcended the conventions and habits of the cinema. Indeed, the many cartoonish references and devices suggest exactly what Godard thought of the standard-issue narrative that he used as an indifferent frame for his speculations and accusations.

In Pierrot le fou, Godard sought to accomplish something that goes far beyond the bounds of the cinema, beyond its familiar genres, conventions, and forms. The stakes are suggested in a scene at a cocktail party, where Ferdinand meets the American director Samuel Fuller and asks him to define the cinema. Fuller responds: “A film is like a battleground. It’s love, hate, action, violence, and death. In one word: emotions.” Rather than have actors act out emotions on-screen, Godard wanted to find a way to signify emotion and thus to arouse it in the viewer—so that emotion would go from the filmmaker to the viewer not analogically but in concentrated, sublimated form, by means of style. The rejection of naturalistic drama in favor of shards of images, voice-over recitations, incongruous insert shots, and intrusive music hall–like interludes is not a deflection or avoidance of emotion but an attempt to evoke—to provoke—an intensity and spectrum of feeling of an ineffably romantic scope, beyond the small-scale personal identification with characters in filmed melodrama.

The film is filled with contradictions: sublime, overwhelming images of nature and acrid gasoline haze (a big ’62 Ford Galaxie convertible that Ferdinand drives into the sea, smoke from a burning car filling the sky above a verdant landscape); the Vietnam War, repeatedly mentioned, suggested, viewed as newsreel footage, followed by a clip of Jean Seberg in Godard’s own 1963 Le grand escroc, which calls into doubt the veracity of documentary filming; Joyce and Beethoven and Balzac and Céline alongside comic books and music-hall comedy and Laurel and Hardy–ish pranks; a gangsterish genre that Godard no longer believed in and a new kind of form that he couldn’t yet find; the self-searching of Ferdinand in the mirror, his allusion to Poe’s “William Wilson,” about a man and his double. Pierrot le fou was the work of a divided person whose film fell into the abyss of his own character.

If Godard was at war with himself, he was in perfect sync with a time that was also at war with itself; and as his personal crises mirrored those of the age, the age looked upon him as its reflection. It was a bind from which only drastic measures would free him. The romantically transcendent self-immolation with which Pierrot le fou would end foreshadows an age of political violence and self-abnegating ideological rigors that would come to take the place of a lost faith, not least in himself.

*****

Pierrot le fou was booed when it premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September 1965, but in Le nouvel observateur the influential critic Michel Cournot wrote, “I feel no embarrassment declaring that Pierrot le fou is the most beautiful film I’ve seen in my life,” and when it opened in France at the end of the year, he virtually wrote in tongues to praise it. In Les lettres françaises, the novelist and poet Louis Aragon waxed dithyrambic in a front-page rave (“There is one thing of which I am sure . . . : art today is Jean-Luc Godard”); these and other critics recognized and mentioned the film’s intense and intimate personal significance.

Pierrot le fou proved a tough ticket in Paris—but, more importantly, it inspired a generation, and most famously Chantal Akerman, who, when she saw it at age fifteen, decided at once to become a filmmaker. The self-destructive romanticism, the artistic self-consciousness, the frenetically unhinged form, the blend of emotional extravagance and cool self-mocking, the vanished boundaries between irony and sincerity and between symbol and reality, the overt cinematic breakdown and breakup, were all of their moment. Pierrot le fou was the last of Godard’s first films, the herald of even more radical rejections and reconstructions to come—for Godard and for the world around him.