The Breakfast Club: Smells Like Teen Realness

“You see us as a brain, an athlete, a basket case, a princess, and a criminal. Correct?”

The first spoken passage in The Breakfast Club, heard in voice-over, is a recitation by Anthony Michael Hall’s character, Brian Johnson, of the letter he has composed on behalf of his fellow Saturday detainees at Shermer High School. As that barbed “Correct?” indicates, there’s some defiance in this tidy taxonomy of teendom, a middle finger to the letter’s recipient, Mr. Vernon (Paul Gleason), the cloddish, unfeeling grown-up who holds the group captive throughout the film. How dare he define us kids with such simplistic, reductive labels!

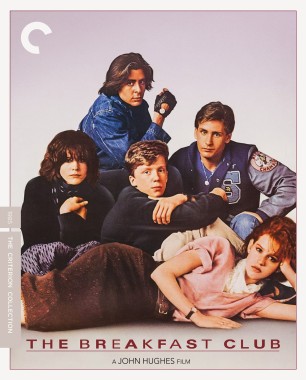

Still, these labels have their use. At the movie’s outset, even the five protagonists are comfortable in these pat identities: Hall’s Brian as the dutiful grind, Emilio Estevez’s Andrew Clark as the square-jawed jock, Ally Sheedy’s Allison Reynolds as the wan, antisocial freak, Molly Ringwald’s Claire Standish as the cosseted popular girl, and Judd Nelson’s John Bender as the combustible, damaged delinquent. It’s all so acutely, contradictorily adolescent: Don’t make me conform to a prescribed identity—and please, God, let me fit in.

This was John Hughes’s great gift in his early films as a screenwriter and director: he understood the whirling, emotionally inconsistent state of being an American teenager better than anyone else working his beat in the 1980s. The Breakfast Club, released in 1985, is the middle film of the “teen trilogy” for which he is most celebrated, bracketed by his first outing as a director, the slapsticky Sixteen Candles (1984), and the more exuberant and polished Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). The trilogy becomes a sextet if you also count the comparatively minor Hughes movie Weird Science (1985) and two further teen-focused films from the period that he wrote but off-loaded to the director Howard Deutch, Pretty in Pink (1986) and Some Kind of Wonderful (1987).

As insightful as he was prolific, Hughes got adolescence correct down to the last detail. The little things in The Breakfast Club register as much as the revelatory, tear-streaked monologues: the conspiratorial eye rolls shared by the alpha kids Claire and Andrew, the unselfconsciously displayed oral fixations of Allison and Brian (she with her compulsive nail-biting, he with his pen-chewing). That Hughes himself was in his midthirties in this period, and had been a happily married man since the tender age of twenty, makes The Breakfast Club all the more remarkable. How did a baby boomer, born in 1950, become the teen laureate not only of the eighties but also—as his films would prove surprisingly durable—of the decades that followed?

Part of the answer lies in the very fact of Hughes’s boomer status. Though relatively late to big-time Hollywood success, he rode the same wave as his peers, experiencing life as part of the first youth market specifically targeted by advertisers, buying new Beatles albums as they came out, upending the old Bob Hope–Rat Pack–Doris Day order seemingly overnight—essentially taking up all the space in the culture. In fact, Hughes’s first foothold in show business came when he placed some articles in that boomer-humor bible National Lampoon, which set the stage for the film that would be his eventual breakthrough as a screenwriter, the hit comedy National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983), directed by Harold Ramis.

For all his achievements, though, Hughes was troubled by the boomers’ ongoing cultural dominance. By dint of having gotten married young, he and his wife, Nancy, were closer in age to their teenage neighbors in suburban Illinois than to those kids’ home-owning parents, and he recognized a demographic unspoken for. “My generation had sucked up so much attention,” Hughes said in a 1999 interview, “and here were these kids struggling for an identity. They were forgotten.”

The Breakfast Club was, therefore, a mission as much as a movie. It wasn’t an opportunistic teensploitation flick—the Porky’s series had that ground covered—but, rather, a cinematic representation of what Hughes was observing in real life but not seeing up on any big screen. He picked up the phrase that became the film’s title, for example, from a friend’s teenage son. “It actually referred to morning detention, not Saturday detention, but I figured no one would call me on it,” he said.

Under its working title, Detention, Hughes’s script was meant to be the first that he would direct himself. But, while waiting to sort out the financing and casting of the film, he quickly wrote a screenplay for a more expressly comedic movie, about a girl whose family, caught up in preparations for her older sister’s wedding, forgets about her sixteenth birthday. This script, titled Sixteen Candles, so impressed Ned Tanen, a former studio head turned independent producer, that he gave Hughes a deal to direct both pictures, provided that he make Sixteen Candles first.

Tanen’s edict served both Hughes and The Breakfast Club well. Sixteen Candles, while not a box-office smash, received good notices and established Hughes’s credibility as a movie director. It also afforded Hughes the chance to purge himself of some puerile, Lampoon-ish inclinations, such as a gratuitous topless-girl-in-shower scene and a crudely stereotypical Asian exchange-student character named Long Duk Dong. Most important, Sixteen Candles gave Hughes the opportunity to develop a rapport with the film’s astonishingly gifted fifteen-year-old lead actors, Ringwald and Hall, both of whom he duly booked again for his next picture.

By the time the Breakfast Club cast assembled in the spring of 1984, Hughes was fully confident in his vision of a minutely observed chamber piece about teen angst that, while sprinkled with humor, was not a comedy. And in his determined quest for verisimilitude, he shot the film on location in the suburbs of Chicago, where he had himself spent his teen years.

Hughes had grown up in Northbrook, a commuter village that had, until 1923, been known as Shermerville. The fictitious town of Shermer, where he would set most of his films, was at once a stand-in for Northbrook and a composite of all the towns and neighborhoods he knew in the area. In his fertile mind, Ringwald’s affluent characters in Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club were passing acquaintances of Matthew Broderick’s Ferris Bueller, while Nelson’s Bender came from the same hardscrabble section of Shermer as Del Griffith, the struggling but relentlessly jolly traveling salesman played by John Candy in the post-teen Hughes comedy Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987).

Playing the role of Shermer High was Maine North High School, a brutalist edifice in another Chicago suburb, Des Plaines, that had closed three years earlier due to declining student enrollment. Hughes used Maine North’s exterior and locker-lined hallways more or less as he found them. The film’s main set was not the school’s actual library but a purpose-built facsimile of the real thing, constructed in Maine North’s gymnasium: an open-plan, seventies-style “learning center” with staircases leading to a terrace.

In its spareness, The Breakfast Club could almost be a black-box theater production: five kids of disparate backgrounds are compelled to spend nine hours together in one room, gaining insights into themselves and each other along the way. Nelson, as the movie’s designated irritant-provocateur, makes the most of the library space; while the other characters, at least initially, adhere to Mr. Vernon’s order to stay in their seats, Bender is all kinetic energy, stalking the room, sprawling on its chairs, angrily sweeping oversize reference books off a reading table. He’s a jerk, but he gets the conversation going, and he’s also the first of the five kids to break down and reveal his vulnerability. When Andrew questions the veracity of Bender’s dramatic portrayal of his violent home life, John pulls up a sleeve to reveal a cigar burn. In so doing, he works himself into a lather of rage that he can resolve only by ferociously vaulting himself up and over the staircase and then curling into a fetal ball.

All of the characters in due time reveal similar holes in their souls, though not in a straight and steady line toward hug-it-out reconciliation. There is tension nearly to the very end. Claire, whose pouffy rich-girl blunt cut is just a few years and a good lacquering away from becoming a Lake Forest society dowager’s hair helmet, is forthright enough in her snobbery to acknowledge that she may not treat her new detention acquaintances as friends come the resumption of normal school life on Monday. Brian (in a magnificently nuanced performance by Hall) moves within the space of two minutes from tearfully expressing suicidal ideation to having a genuine laugh at his own expense.

Hughes demonstrated a Scorsese-like level of commitment to getting what he was after. He shot more than a million feet of film (unheard-of for a low-budget teen flick) and encouraged his young actors to embellish and extemporize. It was Nelson who coined Bender’s sick-burn put-down of Brian as a “neo-maxi-zoom dweebie.” It was Hall’s idea, when his virtuous character is asked why he would want a fake ID, for Brian to answer, “So I can vote!”

This sensitivity to teen realness is what made The Breakfast Club connect with audiences on a gut level, even beyond the white-suburban milieu depicted in the movie. A seventeen-year-old African American kid named John Singleton, in his capacity as his paper’s film critic at Blair High School in Pasadena, California, caught a preview screening early in 1985 and was bowled over. “What I liked most about the picture was that the various characters were teenage archetypes, but they were rooted in genuine human problems,” he says. “I didn’t feel alienated by the fact that they were all white kids. They were just teens finding their way into adulthood—like I was.” It may not be immediately evident, but Boyz n the Hood, Singleton’s 1991 directorial debut, set in peak-gangsta-era South Central Los Angeles, has more than a little Hughes DNA in its varied array of teen characters. “He gave me a template,” Singleton says.

Indeed, we now live in a world rife with writers and filmmakers who regard Hughes as a formative influence. Judd Apatow, who was also seventeen at the time of The Breakfast Club’s release, had been on board since Sixteen Candles, because, he says, “Anthony Michael Hall and the nerds were the first people I saw in a movie who really felt like me.” By the late nineties, Apatow, with Paul Feig, had shepherded the distinctly Hughesian cult-TV series Freaks and Geeks into existence. In the years since, as a director and producer, he has borrowed further from the Hughes playbook, building up a body of funny-poignant work and a motley repertory of recurring players.

The very simplicity of The Breakfast Club’s setup also proved to be an asset—it has kept the movie evergreen, appealing to new audiences as they come along. As fine a film as George Lucas’s American Graffiti is, its hot rods and Brylcreemed teens belong distinctly to 1962, and the timing of its original release, in 1973, in the thick of Watergate, posited the movie as a boomerish meditation on innocence lost. By contrast, The Breakfast Club, apart from Bender’s fingerless gloves, doesn’t play as a period piece or a nostalgia trip. (In the wise words of John Kapelos as Carl the school janitor, a man far more comfortable in his own skin than Gleason’s Mr. Vernon, “C’mon, Vern, the kids haven’t changed. You have.”)

The performer and writer Ilana Glazer, who created the comedy series Broad City with Abbi Jacobson, was not yet born when Hughes’s teen trilogy first came out, yet she was taken, in her own teen years, with how accurately these films caught the eternal spirit of suburban adolescence—“the privilege of being romantic, to create versions of yourself and try them on for practice,” as she puts it—and with how Hughes, uniquely among male filmmakers of his era, understood young women and how they talk. The Breakfast Club’s pot-smoking sequence is something of a forebear to Abbi and Ilana’s stoned high jinks and bull sessions in Broad City, as is Allison’s authoritative declaration that “when you grow up, your heart dies”—patent nonsense, but so true when you’re caught up in a fugue of youthful profundities.

Not that Hughes ever condescended to his teen characters. He simply allowed them to be themselves, which occasionally led to moments of exquisite grace (Allison: “Why are you being so nice to me?” Claire: “’Cause you’re letting me”) and more often led to spasmodic episodes of inarticulacy, horniness, petulance, humiliation, and joy. All par for the course in the teen years, when the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which controls executive function and the regulation of emotions, is not yet fully formed. As Andrew says of the group, “We’re all pretty bizarre. Some of us are just better at hiding it, that’s all.”

This, come to think of it, is an apt summation of the maskings and unmaskings that transpire over the course of The Breakfast Club, and over the course of real-life high school. Hughes was the rare adult who retained access to this volatility, and the even rarer filmmaker who could turn it into art.