Patriotism: The Word Made Flesh

Japanese names in this essay are given in their traditional form: surname first.

Patriotism, or The Rite of Love and Death, poses an unusual question: what impels a novelist to make a film? Actually, few have ever done so. The number has shot up recently, thanks to a surge in China, but for many years the French had the syndrome almost to themselves: Cocteau, Genet, Robbe-Grillet, Duras . . . France took cinema seriously as an art form long before most other countries, so it’s perhaps not surprising that French intellectuals were drawn to the medium. But very few novelists from other cultures followed suit. Might there be an incompatibility between the lines of thought needed to write a book and what Eisenstein called “the film sense”? Anyhow, given that the phenomenon is so rare, what makes some novelists attempt it?

When the Japanese writer Mishima Yukio (1925–70) turned filmmaker for two days in April 1965, to shoot an adaptation of his own short story “Patriotism,” he had at least two primary motives. Let’s take the easy one first. He wanted to create a splash of international notoriety to match the reputation he had already built in Japan. In that sense, the film was a publicity stunt, a gesture calculated to enhance his European profile at a time when he believed himself to be in the running for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He shot and postproduced the film in secret and premiered it at a private screening at the Cinémathèque française in Paris in September 1965. Its first public screening was at the Tours Film Festival (at the time, the world’s most prestigious showcase for short films) in January 1966. As expected, the aestheticized but realistically detailed presentation of a traditional bushi suicide caused a sensation. Some in the audience fainted; Mishima was much talked and written about. Death in Midsummer, the collection containing the original short story, appeared in English translation in 1966, not long after the film’s premiere; it was the seventh of Mishima’s books to be translated.

When news of Mishima’s film broke in Japan, the response was surprise and intense curiosity. (The film was released theatrically in 1966; it’s still the only high-grossing short film ever distributed in Japan.) The Japanese were already used to thinking of Mishima as an oddball. He was the most celebrated novelist of his generation (albeit one with falling sales, despite the steady stream of pulp he produced between the serious novels) and had won his third major literary prize in 1965. But he didn’t behave like other writers.

Mishima meticulously constructed his own celebrity. He was in the papers as regularly as any movie star. He dressed flamboyantly (sometimes in Hawaiian shirts and drainpipe trousers, very often in shades) and socialized with famous friends like Utaemon, a female impersonator from the Kabuki theater. After marrying Sugiyama Yoko in 1958 (she was the nineteen-year-old daughter of a famous painter), he built a bizarre “Western-style” house as their home, complete with a mock-classical statue of Apollo and a Venetian “love seat” in the garden. He took up bodybuilding and found endless reasons to show off his newly sculpted torso. He asked the film company Daiei to cast him in a gangster movie; they gave him the lead in Masumura Yasuzo’s Afraid to Die, and he got to wear a leather jacket, slap Wakao Ayako around a bit, and, crucially, die at the end. He also teamed up with the photographer Hosoe Eiko on an exhibition/photo album called Ordeal by Roses, in which he is shown naked or near naked in a variety of sadomasochistic poses.

The impact of these “pranks” (his own word) was limited to Japan, of course, and that’s why the film of “Patriotism” was aimed first and foremost at the Western audience. Mishima wanted to establish himself internationally both as a novelist and as something more. He prepared versions of the film in English, French, and German, as well as Japanese (he handwrote the scrolling captions himself in all four languages), and chose to counterpoint the film’s assertively Japanese elements with Western music: the “Liebestod” (“Love-Death”) from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. He also stylized the action (most of the original story’s realist detail is abandoned) and placed it in two universally recognizable Japanese settings: a Noh theater stage and (in the final shot) a raked Zen Buddhist garden. Unconsciously following the example of Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour (another half-hour monochrome short drawn from its author’s own writings), he did without speech. All of this was designed to enhance the film’s intelligibility and appeal to non-Japanese audiences—and thus to amplify the effect of the central act of suicide.

There is no Japanese consensus about the origin of seppuku (better known in the West by the more vulgar term hara-kiri, which is why Mishima uses it in the English, French, and German captions—but both words mean “slitting the belly”) as the most honorable way for a bushi to take his own life, but there’s general agreement that the choice of an excruciatingly painful death was intended to symbolize Japanese strength, courage, and resolve. Three years before Mishima made his film, Kobayashi Masaki released his feature Harakiri, which was the first movie to show the act in anything like realistic detail. But Kobayashi’s film was framed as an attack on the inhumanity of Japan’s feudal society and, implicitly, on twentieth-century Japanese militarism. It used its protagonist’s agonizing seppuku as a cipher for everything it wanted to purge from the Japanese psyche. Patriotism is the exact opposite. Mishima goes further than Kobayashi in depicting the spilling of entrails, but his aim is to validate the act as a thing of beauty. Lieutenant Takeyama and his wife, Reiko, are purified by their supremely honorable deaths. In the final shot, their entwined corpses are unblemished and serene.

This brings us to Mishima’s second and more difficult motive for making the film. He had been conscious since his teenage years of an intimate connection between eroticism—specifically, homoeroticism—and violent death. In his first successful novel, the autobiographical Confessions of a Mask, he describes reaching his first sexual climax, at the age of twelve, when he comes upon a reproduction of one of Guido Reni’s paintings of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. To understand how this first spurt of sexual desire evolved into an autoerotic desire for the rapture of violent death—an evolution related to the development of his body, to a growing preference for action over writing, and to a paralyzing inability to feel alive except when approaching death—is the work of a biographer, not a writer of DVD liner notes. (I can strongly recommend John Nathan’s Mishima, published in 1974, which remains the most persuasive account of the man in any language and which contains some very useful pages on the making of this film.) Whatever the process involved, it’s clear that the making of Patriotism in 1965 was one of Mishima’s many rehearsals for his actual seppuku on November 25, 1970.

Mishima planned his own death even more meticulously than he worked on his public profile, and the many symbolic rehearsals were a vital part of the groundwork. They appeared in his writings (the novel Kyoko’s House, 1959; the short story “Patriotism,” 1961; the novel Runaway Horses, 1969), but the impulse to physically act out deaths was too strong to resist. Filming Patriotism was a key first step; Mishima performed seppuku again as an actor in Gosha Hideo’s movie Hitokiri (1969), and posed for a series of death photographs by Shinoyama Kishin—including one as Saint Sebastian and another in the act of committing seppuku—only two months before he hacked his belly open for real. Of course it’s impossible to know what these fantasies meant to Mishima, or why he wanted “to die not as a literary man but entirely as a military man,” as he put it in his last letter to his parents. His careful planning created a situation in which the word could be made flesh, precisely at the point of its own extinction. Perhaps the climactic moment, after the agony, matched the rapturous serenity he imagined in Patriotism.

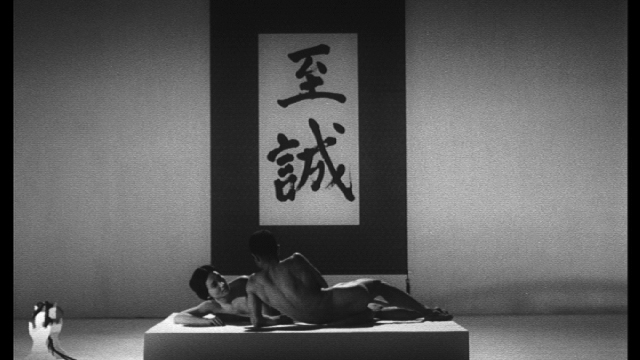

A few footnotes to finish. Mishima’s idiosyncratic reading of “patriotism” is underscored by the kakemono scroll that hangs on the back wall of the stage. The two Chinese characters read “Shisei” (or “Zhicheng” in Chinese), which means “wholehearted sincerity” and carries implications of faith and devotion. Mishima deliberately chose a scratchy 78 r.p.m. recording of Tristan und Isolde for the soundtrack because it was made in 1936, the year in which Patriotism is notionally set. Mishima’s story occurs in the margins of the real-life February 26 Incident, an attempt by young army officers to restore direct rule by the “divine” Emperor Hirohito that involved slaughtering politicians and heads of industry in surprise attacks. (This episode is also invoked in the closing scene of Suzuki Seijun’s Fighting Elegy; the visual touchstone is the snow, since there was famously thick snow on the streets of Tokyo on the night of the coup attempt.)

After Mishima’s death, it fell to his widow, Yoko, to administer his literary estate. She kept his Collected Writings in print and sanctioned a few new translations but did her best to erase memories of his “pranks.” Among other things, this entailed suppressing the film of “Patriotism,” which was not legally screened anywhere between 1970 and 2006—although there were copies in the collections of some cinematheques and academic institutions. This situation changed after Yoko’s death, and the film was published on DVD in Japan in 2006.

One month before he shot Patriotism, Mishima visited London to take part in a conference. While he was in England, he bought the small animal figurines that are used in the film as Reiko’s keepsakes. He also gave an interview (in fluent English) to BBC Television. One of the things he said resonates down the years: “Hara-kiri is a very positive, very proud way of death. I think it’s very different from the Western concept of suicide. The Western concept of suicide is always defeat itself. Mostly. But hara-kiri sometimes makes you win.”