The Burmese Harp: Unknown Soldiers

At the request of the author, Japanese names are given here in their traditional form: surname first.

The Burmese Harp was the forty-one-year-old Ichikawa Kon’s twenty-seventh feature, and the first real landmark in his career. He had entered the film industry as an animator (his first film was a twenty-minute puppet short), but switched to live action the moment he had the chance, fired by his love of films by Yamanaka Sadao and Itami Mansaku, which he’d seen as a young man in the 1930s. Nobody in the industry or the press singled him out as a major talent on the strength of his first twenty-six features, all of them company assignments, although Japan’s smarter critics noticed that Mr. Pu (1953) was an unusually inventive satirical comedy. If anything brightened this journeyman period in Ichikawa’s career, it was his sure and sometimes arresting sense of visual framing and composition; his training as a graphic artist hadn’t gone to waste. But The Burmese Harp (1956) changed everything. It was the last of three films that Ichikawa shot in 1955 for the company Nikkatsu—a brief port of call between his long-term contracts with Toho/Shintoho and Daiei—and he lobbied the company hard to make it. “Oh, but I wanted to make that film,” he told Donald Richie ten years later. “That was the first film I really felt I had to make.”

His enthusiasm was vindicated by the film’s national and international success. It was the first Ichikawa film to appear on Kinema junpo magazine’s annual Best Ten list (it ranked fifth) and the first to be shown outside Japan (it won the San Giorgio prize at the 1956 Venice Film Festival and was sold for distribution in many Western countries). This dramatically raised Ichikawa’s profile: the Japanese press began taking him seriously, and film companies allowed him more leeway than before in his choice of projects.

Nikkatsu had originally assigned the film to the veteran Tasaka Tomotaka (1902–74), largely because he’d made the two best films about the sufferings of Japanese soldiers in war, Five Scouts (1938) and Mud and Soldiers (1939, shot in China). But when he fell ill, the comparatively unknown Ichikawa got his chance. It was a high-profile project, based on an already famous novel, continuously in print since it first appeared as a serial in 1946, in the magazine Aka tombo. The magazine was aimed at young people, but the story was immediately embraced by the adult public, making the subsequent book edition a long-term best seller. The novel was written by a middle-aged professor of German literature named Takeyama Michio (1903–84), who had never set foot in Burma and never had another popular success. It’s sometimes described as a Buddhist primer for kids but in fact has only one page on Burma’s Hinayana Buddhist traditions, in a chapter contrasting the Burmese and Japanese attitudes to life. Takeyama’s obvious aim in writing it was to contribute to the healing of the war’s wounds.

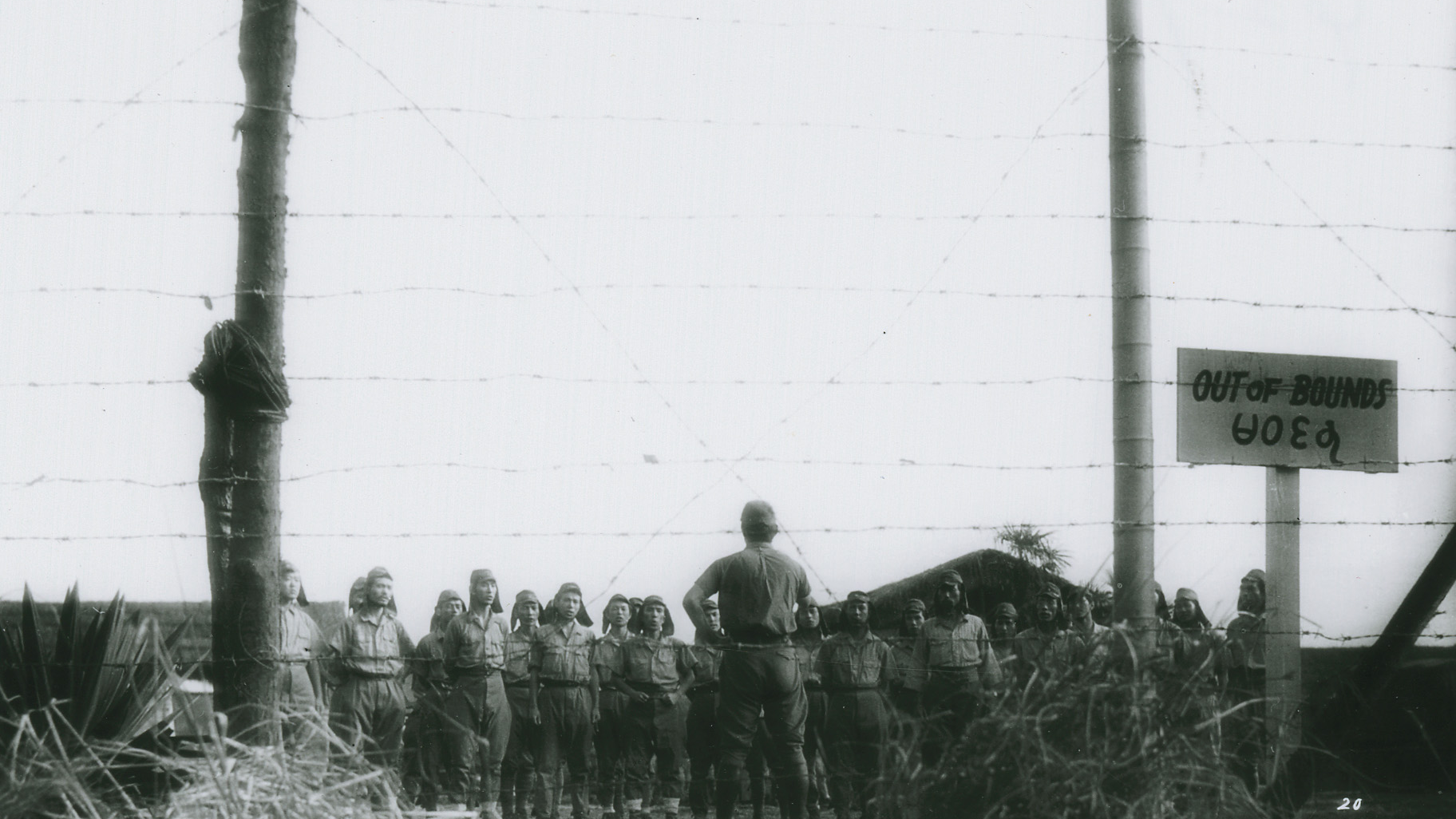

There were plenty of wounds to be healed. In August 1945, with the major cities devastated by Allied bombing, there was widespread poverty and near starvation. The great majority of Japanese at home and on service overseas accepted the news of Japan’s surrender with equanimity and relief, but a few did not. Some isolated army units in Southeast Asia (like the one in the book and the film that Mizushima tries to persuade to lay down its arms) determined to fight to the death, defying or disbelieving their orders from Japan. There was also some right-wing resistance in Tokyo before the U.S. occupation forces arrived: ritual suicides on the forecourt of the imperial residence, a leaflet campaign urging a continuation of the war, and at least one violent skirmish between fanatics and police. And once the GIs did show up (and failed to behave like the vengeful demons many had been expecting), a mini crime wave swept through the rubble of the cities; black marketeering, prostitution, and various yakuza-led scams were rife. Meanwhile, the thousands of soldiers who were repatriated to Japan in 1945–46 found themselves treated as the lowest of the low; many citizens now saw them as an embarrassment.

(We should note in passing that even now Japan’s far right remains unreconciled to the surrender. Japan has expressed “regret” for its invasion of nearby countries but has never formally apologized for the criminal atrocities carried out by its troops. Prime ministers and other government officials continue to visit the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, which honors the spirits of Japan’s military dead, including a number of executed generals who were convicted as class A war criminals, and their visits still inflame resentments in China, Korea, and other countries. And right-wing extremists—always visible throughout Japan, bellowing propaganda from battle wagons festooned with banners—still routinely threaten terrorist actions. For example, when Matsui Minoru’s epic documentary Japanese Devils was screened in small indie cinemas in 2000, there were several bomb threats. In the film, former soldiers speak frankly about war crimes they committed in China.)

Takeyama’s novel is presented as a reminiscence from an unnamed soldier who has fought and been a prisoner of war in Burma. The author sees this man’s company disembarking on the Yokosuka docks and is struck by how much happier and healthier they look than the other returnees. This company is different, we’re told, because the men sing; their captain, Inouye, was drafted from music school and led them in choral singing throughout their tour of duty. The soldier’s account centers on the disappearance of the company scout Mizushima Yasuhiko, who has “gone native,” to the extent that he can pass for Burmese when he wears a longyi, and who has discovered a magical natural skill for playing the Burmese harp. Mizushima disappears after being “volunteered” to persuade a recalcitrant unit to surrender to the British Army, and much of the book is taken up with speculation about his fate; all is finally revealed when Inouye reads aloud a long letter from Mizushima on the boat carrying them back to Japan.

The “big idea” underpinning this story is that music is a salve for the soul: its uses in combat (to send coded signals and to keep up morale) are trumped by its inherent beauty, its capacity to build bridges between opponents, and the way it can express feelings that cannot be stated in words. Takeyama was apparently inspired by the discovery that the song “Hanyu no yado,” known to all Japanese, is actually a version of the English folk song known to Westerners as “Home, Sweet Home.” Hence the scene (faithfully reproduced in Ichikawa’s film) in which Captain Inouye’s company surrenders without bloodshed to Anglo-Australian troops after both sides have sung the song. Homesickness is universal, it asserts, and so is the power of music.

Takeyama, writing in 1946, would not have been aware of the extent or magnitude of the Japanese war crimes committed in Burma and other countries. Such embarrassments have never been widely acknowledged or reported in Japan, and so it’s entirely possible that Ichikawa was equally unaware of them a decade later. (This didn’t save him from attack by film scholar Joan Mellen, who criticizes the film as “a sentimental if often beautiful whitewash of the Japanese presence in Southeast Asia.” But the film makes it plain that the Burmese hate the Japanese, and it shows that some Japanese soldiers were militarist fanatics.) In any case, neither the book nor the film is an exercise in self-flagellation; both emphasize (a) the appalling human cost of war and (b) an alternative to the militarist spirit that had dominated Japan through the 1930s and the war years. The popularity of the book and film suggests that these emphases spoke loud and clear to the shell-shocked Japanese public in the 1940s and 1950s.

But Ichikawa’s film is sharper and more clearheaded than Takeyama’s book, perhaps because it reflects an encounter with the reality of Burma and the Burmese. Most details in the film are taken directly from the book, although the overall structure has been changed: Takeyama sticks rigorously to his narrator’s point of view and reveals Mizushima’s vocation (to bury the Japanese dead in Burma) only when his letter is read on the boat home, whereas Ichikawa provides a lengthy flashback to explain everything much earlier in the film—and shows twice the accidental encounter between Mizushima-as-monk and his former colleagues as they cross a bridge, once from each party’s point of view.

Yet it’s with the dropping of one of the book’s episodes entirely and substituting ideas of his own that Ichikawa provides the measure of the film’s achievement. After Mizushima is sent on the futile mission to persuade a belligerent captain to surrender, he’s wounded in the leg by a British bullet and left to die. (The captain, incidentally, bullying his men into a suicidal last stand in the cave, is Ichikawa’s first and last word on militarist stupidity, the opposite of the kindly Captain Inouye.) In the book, Mizushima is found and nursed back to health by a non-Burmese tribe of cannibals, who plan to eat him; the entire wretched episode is a reminder that Takeyama initially aimed his book at children. Ichikawa instead has Mizushima brought back from near death by a Buddhist monk, who intones over his patient the line “Burma is Burma. Burma is the Buddha’s country.” After his recovery, Mizushima shamelessly steals the monk’s robe (his only thought is self-preservation, and he needs a disguise) and makes his way south, intending to rejoin his company, which is where Ichikawa’s story line rejoins Takeyama’s.

The film, in other words, is closer to Buddhism than the book is. Ichikawa anchors Mizushima’s gradual discovery of his own spirituality in that initial act of theft, a selfish crime that contains the seeds of the thief’s selfless future. For Ichikawa, Burma is, indeed, Buddha’s own land; he films mostly landscapes and temples, generally in wide-angle shots, always stressing the weight of the land and the places in the lives of the humans who pass through them. (When he shows the faces of Burmese in close-up, they are always silent: observing, judging . . .) It’s Burma that turns Mizushima from a fake monk into a real one, and it’s the corpse-strewn Burmese landscape (stained bloodred, as the opening and closing caption reminds us) that guides this young monk to his vocation. Mizushima is deeply conflicted: part of him longs to rejoin his comrades and return to Japan, but the need to right spiritual wrongs overwhelms him, and he elects to stay. Notionally serving Japan, he behaves in a way that most Japanese find baffling. In his way, Mizushima is as “unknown”—and unknowable—as the dead soldiers he cremates and buries.

Ichikawa underlines the point by giving the last word to another unknown soldier, in the closing scene on the boat. By tracking in to a close-up of this man, previously barely glimpsed in group shots, Ichikawa identifies him as the one who has provided an intermittent narration on the soundtrack—the film’s equivalent of the soldier who tells the author of the book what happened in Burma. Like the others on the boat, he’s thinking about what he’ll do when he gets back to Japan. He confides that he was never impressed by Mizushima . . . and wonders how anyone will be able to explain matters to Mizushima’s parents. There’s a final shot of Mizushima crossing the Burmese plains, but Ichikawa cunningly leaves the unknown narrator’s words hanging in the air. Inouye’s company was an anomaly in the Japanese army, and Mizushima is an anomaly in the company, and both are in some sense victims of a bloody, ugly war.

There’s a curious postscript to all this. Nikkatsu treated The Burmese Harp as what we would now call an “event movie” and released it in two parts, three weeks apart. Part one (running 63 minutes) opened on January 21, 1956, and part two (80 minutes) opened on February 12, both with B features. The total running time of 143 minutes was cut to the current 116 minutes when the two parts were combined for rerelease and export—reputedly to Ichikawa’s dissatisfaction. In 1985, Ichikawa himself remade the film in color. The new Burmese Harp, financed by Fuji TV after Toho turned it down, was rather obviously influenced in tone and visual rhetoric by Oshima Nagisa’s Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, released two years earlier. Ichikawa used the same script that his late wife, Wada Natto (1920–83), had given him for the original, and again cast the inimitable Kitabayashi Tanie as the old Burmese woman trader who speaks a little Osaka-accented Japanese. It pleased young filmgoers enough to become the top-grossing Japanese film of 1985, but didn’t repeat the international success of the original.

This essay was originally published in the Criterion Collection’s 2007 edition of The Burmese Harp.