The Front Page: Stop the Presses!

The Front Page is the zestiest and most influential movie you’ve never seen. A critical sensation and a runaway hit in its original theatrical form in 1928, the play proved even more of a trendsetter when it first hit the screen in 1931. It became famous, sometimes infamous, for its frankness about sleazy backroom politics and reckless, sensationalistic newspapers, and for its suggestive patter and profanity. It brought a crackling comic awareness of American corruption into popular culture, and it made rapid-fire, overlapping dialogue fashionable, turning Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur into the hottest writing team around, on the Great White Way or in Tinseltown. It also augmented Lewis Milestone’s stature as a director and Howard Hughes’s as a producer. When Hughes released the movie, he put his and Milestone’s names on the opening card, before the title. When the credits roll in a mock-up of the Morning Post, the byline for Hecht and MacArthur runs right beneath the banner headline, The Front Page. (Actually, Hecht and MacArthur had demanded too large a screenwriting fee, so Bartlett Cormack, a reporter turned dramatist, did the adaptation, and Charles Lederer, who would go on to write Howard Hawks’s remake, His Girl Friday, supplied additional dialogue. They both stuck close to the original play.)

The Front Page movie has been reincarnated on the big screen three times and endlessly mimicked, and the play has traveled around the world and been revived periodically on TV and on Broadway. (An all-star production with Nathan Lane, John Slattery, and John Goodman is being mounted as these notes go to press in late 2016.) Milestone’s film came out on low-cost home video starting in the 1980s and then, in 2015, on a Kino Classics Blu-ray mastered from a 35 mm preservation print held by the Library of Congress. But those reissues weren’t exactly Milestone’s picture, the one that even a tough cookie like critic Dwight Macdonald said was “widely considered to be the best movie of 1931,” not just in Hollywood but anywhere. And though The Front Page’s brash entertainment value broke through even in the shabbiest releases, modern audiences were not able to see itin all its glory until 2016, after a stunning discovery by the Academy Film Archive.

The backstory to this Front Page is revelatory. In 1931, Hollywood directors were shooting their films on three separate negatives to create prints for domestic, British, and “general foreign” markets. Cast and crew invariably saved their best efforts for the American version: the freshest, bounciest performances, the sharpest or most fluid camera work and staging, the keenest beats and cadences.

For the other versions, filmmakers often rewrote scenes, substituting language and references that would be easier to grasp in other parts of the world. In 2014, the Academy set out to restore The Front Page from a 35 mm print that had been part of the Howard Hughes film collection at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Consolidated Film Industries had struck it in 1970 from an original nitrate negative (which was not saved), and the Academy’s restorers thought they could rely on the Library of Congress print to replace any damaged portions. But they soon discovered that each institution possessed a different version of the movie. Comparing the celluloid evidence with information gleaned from the production files in Milestone’s papers, the Academy determined that the Library of Congress copy, like all those distributed for the last sixty or seventy years, originated from the general foreign negative, while its own came from the American one. Here was Milestone’s optimum cut, and after being essentially lost for more than half a century, it was presented in a new restoration at the 2016 Montclair Film Festival and later that year at Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival. The screenings were an eye-opener for movie lovers and a tribute to archivists.

Now it’s possible to appreciate this movie’s colloquial punch and showbiz razzmatazz without having to make allowances for dead spots or busted tempos. As a fan of the play, I had always wondered why “Pocahontas” became “Lady Godiva” in a riff about a Peeping Tom, why a male doctor dubbed the Electric Teaser for treating wives with a jolt of electricity became a Swedish masseuse doing the same for husbands, and why New York newsmen were not called “lizzies” but instead said to “use lipstick.” (As it turns out, one bizarre, witless vulgarity—a gentleman of the press giving the middle finger to the mayor—appeared only in the general foreign version.)

What’s most elating about Milestone’s preferred cut is not merely the restitution of more authentic language but the reclamation of more vibrant rhythms and images. Mark Twain said, “The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—’tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.” The same goes for visual compositions. In this Front Page, the right shots take the place of the almost right shots—and the result is galvanizing. When the lens takes in a two-shot of opposing journalists instead of a wide shot of the entire company, or when a star reporter who’s “going New York” spits out his new address to his colleagues, then writes it on the wall in one unbroken move—instead of t’s not just great “filmed theater”; it’s also a real live movie.

Real Buddies Invent the "Buddy Movie"!

This film deserves so much praise that it’s easy to spread around, but the authors must come first. Next to bootleg alcohol and meatpacking, Ben Hecht was the Windy City’s most profitable industry of the day. Born in New York City and raised in Racine, Wisconsin, he came of age during the Chicago Renaissance of the 1910s and ’20s, making his name as a reporter and columnist for the Chicago Daily News while starting to produce the torrent of fiction and nonfiction, plays, and, later, screenplays that would propel him to New York and then Hollywood. His slangy eloquence, his brilliance at scene-making, and his nose for the zeitgeist fostered a slew of smash movie classics, including the seminal silent gangster film Underworld (1927), which won the first Oscar for best original screen story, and its sound-film successor, Scarface (1932); the screwball satire Nothing Sacred (1937); and the seductive romantic thriller, Notorious (1946).

Though Hecht and Charles MacArthur overlapped in Chicago and even collaborated on cracking a murder case, they didn’t become best pals and cowriters until they reconnected in New York and dreamed up their landmark newspaper comedy. In the play The Front Page, they stretched their plot as tight as a snare drum, with every facet rattling trippingly on the surface—for the audience, if not for the characters. Their crooked pols and jaded newspapermen were patterned on (and often named after) bigger-than-life personalities in Chicago government and journalism, and they based the story on two real-life incidents: convicted killer Tommy O’Connor’s breakout from the Cook County Jail, and Chicago Herald and Examiner editor Walter Howey’s attempt to keep MacArthur from running off to marry a “sob sister” reporter by having him arrested at the Gary, Indiana, train station. In The Front Page, Walter Howey becomes Walter Burns (played by Adolphe Menjou in the film), editor of the Examiner. He won’t let go of his ace reporter, Hildy Johnson (Pat O’Brien), who plans to marry a conventional beauty, Peggy Grant (Mary Brian), and move with her to New York, where a job is waiting for him at her uncle’s advertising agency. (Hecht and MacArthur also modeled Hildy partly on John Hilding Johnson, the Herald and Examiner’s reigning crime reporter in the roaring twenties.)

Burns and Johnson never stop sparring over whether a man with printer’s ink in his blood can settle into a regular job and homelife. Meanwhile, Chicago’s most controversial criminal—a mild-mannered anarchist named Earl Williams (George E. Stone)—becomes a political football. Confused and adrift after losing his long-held job, Williams has killed a cop. The sheriff and the mayor have scheduled Williams’s execution close to Election Day in a cynical maneuver to appeal to the city’s large African American voting bloc (the policeman was Black). As the action zips along, the governor issues a pardon on the grounds that Williams suffers from dementia praecox (schizophrenia). But the city officials ignore the pardon. Each climax kicks Williams’s fight for life, and Hildy’s fight for his marriage, closer to resolution. The structure is airtight; the subplots click together like the tumblers in a time lock set for 101 minutes.

Even in the pre-Code 1930s, only a maverick like Hughes could have brought this cheeky cavalcade to the screen with irreverence intact. And he recognized talent: Milestone had directed Hughes’s rollicking production of Two Arabian Knights in 1927, winning the only Academy Award ever given to a “best comedy director.” Hughes also must have known that Milestone and Hecht had become buddies a few years earlier in Florida. Hecht made a mint publicizing the Sunshine State’s 1925 real-estate boom, then did some rewrites on The New Klondike, a romantic comedy about baseball and land speculation that Milestone directed in Miami. They renewed their friend-ship in Hollywood, where Milestone shared a house with rising MGM employee David O. Selznick and Selznick’s brother Myron, soon to become the first superstar agent. According to Milestone, Hughes disapproved of his top choices for Hildy, James Cagney (“a little runt,” Hughes complained) and Clark Gable (“His ears are so big they make him look like a taxi with both doors wide open”), but otherwise the producer let the director make the picture his own way.

Like most great pioneer filmmakers, Milestone led an adventurous life before he hit the soundstage. Born Leib or Lev Milstein (the violin virtuoso Nathan Milstein was his cousin) in 1895, he received his core education in Kishinev, Russia (now Moldova), then studied at a German engineering school. He swapped his return train fare to Russia for a ticket on a boat to America. An aunt helped him get through his first months in New York, but his father, a clothing manufacturer, advised him by letter, “You are in the land of liberty and labor, so use your own judgment.” He did manual work and sales jobs until he landed a position as a photographer’s assistant. When World War I broke out, he enlisted in the Signal Corps and took a six-week course at the U.S. School of Military Cinematography, based at Columbia University. He posted to the propaganda division of the Army War College in Washington, D.C., and ended up hoisting equipment for a cameraman documenting Medical Corps operations, making hygiene films, and editing combat footage. His cutting skills won him a Hollywood job when he was mustered out of the Army in 1919, and he soon started working as an assistant to top director Henry King and comedy specialist William A. Seiter. The New York Times critic called Milestone’s first feature, Seven Sinners (1925), made for Warner Bros., the best recent picture he’d seen at Warner’s flagship theater, but Milestone chafed at studio demands. Happily, Hughes soon formed his own company, and, in 1927, the young director went to work for him.

Milestone had drive and, as he put it, “chutzpah,” as well as a sardonic comic sense akin to Hecht’s. When he was preparing to shoot his wrenching antiwar film All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) from the point of view of German schoolboys who become soldiers, Universal cofounder and president Carl Laemmle pleaded with him for a “happy ending.” Milestone replied, “I’ve got your happy ending. We’ll let the Germans win the war.” He won his second Oscar for that film. When he moved on to The Front Page, he planted in-joke references to showbiz colleagues like George Cukor, who’d been the dialogue director on his World War I epic, following the playwrights’ lead for naming melodramatis personae.

Hecht and MacArthur’s writing is so potent that the play has often been considered “director-proof,” but it’s actually a tough nut to crack. Hecht and MacArthur set out to expose the yellow press that blithely shades and fabricates stories and reduces its subjects to stick figures. The reporters relentlessly mock the befuddled killer’s bighearted streetwalker supporter, Molly Malloy (Mae Clarke); they think she’s living in a self-created soap opera. In the most daring tonal shift in any smash American comedy of its time, Molly shames the reporters while proving she’s a heroine who’d do anything for a friend. But as the playwrights delved deeper into their Chicago experience, they altered their point of view. As they put it in an epilogue to the third printing (widely attributed to Hecht alone), “The iniquities, double dealings, chicaneries, and immoralities which as ex-Chicagoans we knew so well returned to us in a mist called the Good Old Days.” The result was “a valentine thrown to the past.” As the subplots thicken in the pressroom of Chicago’s criminal court building, good does triumph over evil—or at least, better beats worse—and the hard-nosed rivalries and shenanigans of the reporters meld into a grungy yet invigorating esprit de corps.

The Gang’s All Here

Hecht and MacArthur created a slaphappy, creative press gang that indelibly expressed the authors’ own mix of cynicism and sentimentality. Milestone and his actors brought each inky wretch to life, specifically and wonderfully—including Edward Everett Horton at his most hypersensitive and hilarious as the germophobic would-be poet Roy Bensinger; Walter L. Catlett as the callous Murphy; Frank McHugh as his near namesake McCue, an elongated leprechaun with an odd hollow laugh; and the wildly unorthodox Matt Moore as Kruger, a banjo-strumming loafer who seems half-asleep when he’s calling in a story. As Fred Howard’s Schwartz, Phil Tead’s Wilson, and Eugene Strong’s Endicott man the phones directly connected to their newsrooms, they overhear each other making up or embellishing the “facts.” These reporters play a nonstop game of can-you-top-this, except for Kruger, who mostly strums “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” and reports nothing, which means he’s more accurate about 90 percent of the time.

This Front Page does make sure we realize that the authorities the newsmen pillory, whether in actual reporting or fabrications, deserve our disdain. The funniest moments are when the reporters provide their news desks with deadpan parodies of the sheriff (Clarence H. Wilson) preparing for an armed Bolshevik takeover of Chicago, even though Williams is an anarchist. The reporters may be heartless, but they do have professional scruples. When they eavesdrop on Bensinger inserting a plug for a restaurant into his story about Williams’s last meal, they’re suitably outraged. Demanding free hamburgers from the cop who caters to the pressroom is one thing; they figure he can get them gratis anyway. Outright graft like Bensinger’s is beyond the pale.

When he was in top form (as he also was on Hallelujah, I’m a Bum!, from a Hecht scenario, and Of Mice and Men, from John Steinbeck’s novella), Milestone could balance astringency with humor, stylization with realistic details—his peak films are directorial high-wire acts. In The Front Page, working with production designer Richard Day and cinematographer Glen MacWilliams (with an assist from the uncredited camera ace Hal Mohr), he maintains a cinematic style even when the setups are utterly theatrical. His astute blocking and compositions give us a mental fix on each reporter’s place in the pressroom, so he can pull off little jokes, like Kruger’s banjo suddenly appearing from out of frame as a makeshift collection box from which he can grab his tickets to the execution. He achieves some spectacular effects, like the camera traveling with Molly as she confronts a row of reporters—it’s as if she were a prisoner facing down a firing line. He uses camera movement not merely to generate visual sweep and oomph but to put us in the shoes of the characters. When Hildy says good-bye to his colleagues at the table, the camera pulls away with him and seems to complete each of their farewells. In one glorious moment, as the reporters mock the sheriff, their faces blur and twirl out of the frame like the fruits in a one-armed bandit.

You could savor these showier strokes, though, even in the general foreign version. What’s wonderful about the new version is its overall flow, the strengthening of O’Brien’s and Menjou’s performances, and the restoration of some note-perfect dialogue. O’Brien’s relative softness makes his Johnson a better target for Burns’s manipulations. He gives a surprisingly varied performance: when he’s relaxed, there’s a Gaelic lilt to his voice, and when he’s pumped, he rattles off words like an auctioneer. Menjou, astonishingly, received his only Academy Award nomination for this movie—and he deserved it. He imbues Burns with distinctive qualities: streetwise suaveness and a cruel, almost sadistic nonchalance.

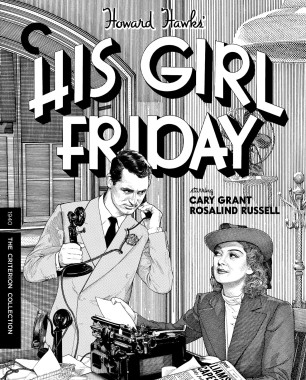

With this play and picture, Hecht and MacArthur helped to establish the buddy-movie paradigm of men trying to save a comrade in arms from the existential dangers of love and marriage. Hecht and MacArthur virtually transferred the plot to the raj with Gunga Din, which Hawks was set to direct (before George Stevens took over), and later, Hawks transformed the template by changing Hildy into a woman and creating an ideal blend of workplace comedy and romantic farce in His Girl Friday.

A Love-Hate Story, Any Way You Dress It

Both movies do a confident, inventive job of “opening up” the play at the beginning, then funneling all the tension and farce into the criminal court pressroom. But Hawks tailors the material to Cary Grant’s brash glamour, as Burns breezes through the newsroom and charms Hildy’s groom-to-be at a nearby café. When Milestone takes you on a tour of the Morning Post, the camera follows Menjou’s Burns as he strides through the printing plant, with the heavy machinery of a thriving industry rumbling behind him. Milestone, who never stops alternating melodrama and comedy, puts a period on that heroic shot when Walter arrives at an empty loading dock where his henchman Diamond Louie (Maurice Black) plays craps with a bunch of lugs. In a series of stylized vignettes, Louie’s men go looking for Hildy, through the grill of a speakeasy’s door, in the mirrored foyer of a brothel, and backstage at a theater while a chorus line kicks by with their comely backs to the camera. Hildy, of course, is with his fiancée, getting their marriage license at City Hall. Milestone quickly counterpoints the couple’s bliss with Peggy’s recognition that Hildy is too excited about telling Walter he’s quitting. Mary Brian cuts a strong figure as Peggy, playing her as smart, not clinging. Still, Milestone emphasizes from the outset that The Front Page is a love-hate story between two clever, driven men.

Milestone’s The Front Page presents Hecht and MacArthur’s original play perfected yet still in the raw—with its male chauvinism and meanness as well as its gallantry in full view. These men may goad Molly Malloy nearly to her death, but they mostly laugh and cheer when Hildy kisses Jenny the scrubwoman and dances her out of the pressroom. This movie captures every bit of the remarkable texture that Hecht and MacArthur put into their play—what theater critic Brooks Atkinson called “the alertness, cynicism, shrewdness, penury, and exuberance of the newspaperman,” in a work that is “rudely realistic in style, but romantic in its loyalties and also audaciously profane.” Its restoration should be front-page news.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2017 edition of His Girl Friday.