His Girl Friday: The Perfect Remarriage

A woman in a flashy striped coat and matching hat strides through the newsroom of the Morning Post, greeting switchboard operators, reporters, the relationship columnist (“How’s advice to the lovelorn?”) with savvy familiarity, until she reaches the office of the editor in chief and barges in, without knocking. And there he is, Walter Burns, electric razor running, facing a sharp-dressed gangster who’s advising, “A little more on the chin, boss”—the chin being the world-famous dimpled one of Cary Grant.

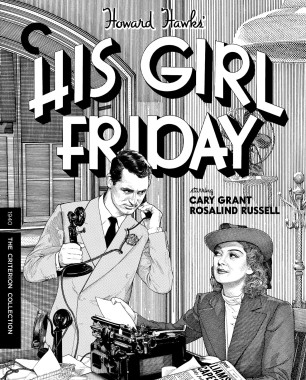

This clacking, chaotic newsroom is a tough world, just how tough we will shortly find out. But as played by Rosalind Russell, Hildy Johnson is more than at home in it—she rules it. And what more perfect director to have his camera gracefully tracking her every step than that lover of tough, intelligent dames Howard Hawks?

More than ten years earlier, in 1928, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur had scored a major Broadway hit with The Front Page and its story of Walter Burns, the spectacularly amoral editor of a Chicago daily, and his ace reporter, Hildebrand “Hildy” Johnson, who wants to get married and go all soft and domestic. Play became movie in 1931 via director Lewis Milestone, from a hard-boiled script by Bartlett Cormack and Charles Lederer that hewed closely to the stage version. Hawks swore he got the idea to make Hildebrand into Hildegard during an after-dinner reading of the play at his house sometime in 1938. According to Hawks, it just so happened that all he had was a woman to read the part of Hildy; Hawks, naturally, was Walter. The gender switch worked so well that before you knew it, he was finding a scriptwriter to turn tipsy dinnertime reading into cold-sober studio production. Alas, Hecht was busy working up scenes for another immortal couple for Gone with the Wind. So Hawks got Lederer, the next best thing to Hecht in these circumstances.

As Todd McCarthy hints in his biography of Hawks, it’s possible that that mixed-up Front Page reading never happened. Over many years and retellings by the director, no woman stood up, Spartacus-like, to declare, “I am Hildy”—in fact, nobody recalled attending such a reading at all. Nobody, that is, except Hawks. Maybe it seems natural now—look at the character’s jokily effeminate nickname—but Hildy was played by the bullet-headed tough guy Pat O’Brien in Milestone’s talkie; Burns was Adolphe Menjou at his slipperiest and least endearing. There was no more obvious logic to putting a woman in O’Brien’s place than there would have been to substituting Jean Arthur for Humphrey Bogart as Philip Marlowe. Wherever he got the idea, His Girl Friday (1940) reflected the Olympian genius of Howard Hawks.

Early in the thirties, Hawks was well-known for action-packed dramas heavy on male dynamics, both friendly and un-, such as 1930’s The Dawn Patrol (his first sound film) and the immortal 1932 Scarface. But in 1934, he had proved himself a master, too, of screwball comedy, helping to alter the course of Carole Lombard’s career by casting her as a spoiled (but canny) Broadway actress in Twentieth Century, opposite John Barrymore’s roaring, egotistical director. By the end of the decade, Hawks was on a roll with his unique approach to romance, delivering perhaps the ultimate screwball comedy, Bringing Up Baby (1938), and, the year before His Girl Friday, Only Angels Have Wings, which combines the adventures of a South American airmail service with a Cary Grant–Jean Arthur love story so adroitly that the film still defies categorization.

Over the years, Hawks had developed a refined understanding of how romantic comedy works. The audience must be convinced that the central couple are made for each other; a screwball comedy’s own particular cleverness lies in keeping the lovers apart for as long and in as crazily creative a way as possible. Remarriage plots are the most grown-up variation, because these are the movies that say two people can be perfectly suited and still louse it up. Matching (or, if you will, marrying) this device to The Front Page, so famous for its bite and cynicism, resulted in the most bracingly adult screwball comedy (and romance) of them all. Hawks and Lederer found a fresh spin on the remarriage comedy, making the question not how the wandering spouse will find her way home but how she’ll get back to work.

His Girl Friday plays out against an especially grim plot mechanism: the question of whether a man will be hanged the next morning for shooting a police officer. Walter suspects that the convicted man, Earl Williams (John Qualen), was temporarily insane and should be reprieved, or, at any rate, he thinks that angle would make a great story. Alas, his ex-wife and best reporter, Hildy, has just arrived with a rock on her left hand and insurance salesman Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy) in tow, ready to take the sleeper train to married bliss in Albany. Soon the unapologetically amoral Walter has conned Hildy into doing a front-page interview with Williams. To keep Hildy writing—and keep her, period—there is very little Walter will not countenance: kidnapping, theft, counterfeiting, and lies of every imaginable description are all fair game. As Hildy tells him, “Oh, Walter, you’re wonderful, in a loathsome sort of way.”

From Nothing Sacred, where Fredric March actually socks Carole Lombard in the jaw, to Hawks’s own Bringing Up Baby, where Grant spends most of the movie begging Katharine Hepburn to get lost, screwball comedies seldom highlight chivalrous gestures. His Girl Friday positively revels in their absence. From her ex, Hildy gets none of the little courtesies that in 1940 were supposed to make women feel respected. Walter pulls out his cigarettes without a word to Hildy; she asks for one and he tosses it to her, and the matches soon follow—no Now, Voyager rituals here. Hildy ribs Walter for wearing his hat inside, he lets doors slam practically in his ex-wife’s face, his restaurant etiquette is unspeakable. Played by anyone other than Cary Grant, Walter might be the least likely love match imaginable; but he is Cary Grant, thank goodness, and, as Manny Farber put it, who else could “get away with so much Kabuki-like exaggeration, popping his eyes, jutting out his elbows, roaring commands at breathtaking speed in a gymnasium of outrageous motion?”

We know from their first scene that Walter and Hildy are made for each other, that they are to bickering what Astaire and Rogers were to ballroom dancing. They snap responses like ping-pong volleys and interrupt to mimic each other precisely. Hildy may holler at Walter for getting her fiancé arrested and kidnapping her prospective mother-in-law, but she secretly enjoys his duplicity. Watch for Russell’s amused, appreciative listening while Walter soft-soaps Bensinger (Ernest Truex), reporter and poet manqué of the Tribune, into thinking he might have a job with the Morning Post. Observe their near-psychic rapport when Hildy is frantically typing up the biggest story of her career, even as poor Bruce pleads for her to leave with him: “What was the name of the mayor’s first wife?” she barks at Walter. Instant response: “The one with the wart on her?” “Right.” “Fanny.”

There’s simply no chance for Bruce, the insurance salesman whose chivalry comes dressed in a raincoat and galoshes, because it looked a bit cloudy that morning. Bruce is “kind, he’s sweet, and he’s considerate,” says Hildy, to the tune of a little hoo-hoo noise from Walter. While not truly dumb, Bruce is several beats behind everyone else in the movie. Bellamy’s just talking at a normal rate, but everyone else is running a verbal Indy 500.

That is never truer than in the City Hall pressroom, where a gang of reporters (Truex, Porter Hall, Cliff Edwards, Roscoe Karns, Frank Jenks, and Regis Toomey) are waiting for Williams to be hanged the next morning. Williams appears to have been based on a far tougher real-life murderer, “Terrible” Tommy O’Connor, who in 1923 escaped from a Windy City courthouse shortly before his scheduled execution and vanished without a trace. Hecht and MacArthur took that idea, added reporters and their swift, slangy, sardonic talk, and wove it together with Chicago’s seemingly eternal political corruption. The reporters are not nice, but they are delightful in their cynical way—tied to the phones, running in and out, double-crossing one another. Hawks maintains the original’s savagely competitive spirit but lightens the mix with a greater emphasis on masculine comradeship, having the boys finish each other’s thoughts like old married people.

Given that easy fellowship, it is easy to see why generations of journalists cite His Girl Friday as the reason they joined the business. Walter in particular is practically an entry-level class on his own. Reviewing Hildy’s big story, and told she mentions the Morning Post in the second paragraph, he snaps, “Who reads the second paragraph?” Not to mention the lesson in breaking-news priorities that Walter delivers to the long-suffering subeditor Duffy (Frank Orth): “Junk the Polish corridor . . . Take Hitler and stick him on the funny pages!” And the immortal advice “No, no, keep the rooster story. That’s human interest.”

The Front Page came ready-made with impressive talk; Lederer improved it, then Hawks turned it up a notch more, by encouraging his cast to ad-lib. Ad-libbing wasn’t necessarily the way Rosalind Russell usually worked. She had long been an MGM actress, with all the smooth systems and star treatment that implied. She wasn’t used to a director who, as she recalled, “sprawled in a chair, way down on the end of his spine,” and said nothing while the actors fired away. In one case, literally; in an early scene, Russell impulsively threw her handbag at Grant, who responded, “You’re losing your arm; you used to be better than that,” and Hawks left it in.

Russell came on board knowing that Hawks had already passed the script to nearly every fast-talking, high-hat dame in town: Katharine Hepburn, Jean Arthur, Carole Lombard, Irene Dunne, Claudette Colbert. That clearly stung. Russell had already proved her comic ability—and how—with her busybody Sylvia Fowler in The Women, directed by George Cukor the year before. And she had to fight for that part too. In her autobiography, she titled the His Girl Friday chapter “Back Door to The Front Page, or How I Was Everybody’s Fifteenth Choice.” But from a rocky start, Russell and Hawks wound up with a keen appreciation of each other, which manifested itself in typical Hawks fashion. “Hawks was a terrific director,” wrote Russell; “he encouraged us and let us go. Once, he told Cary, ‘Next time give her a bigger shove onto the couch,’ and Cary said, ‘Well, I don’t want to kill the woman,’ and Hawks thought about that for a second. Then he said, ‘Try killin’ ’er.’”

His Girl Friday has virtually no score, yet it’s one of the most musical movies of its era, each scene set to the fascinatin’ rhythm of that dialogue. As much as she came to love the process—“We went wild, overlapped our dialogue, waited for no man”—Russell wanted her fair share of laughs and hired a side writer (said to be her own brother-in-law, an adman named Chet La Roche) to punch up her lines and eventually even Grant’s.

Russell still worried a bit that audiences wouldn’t keep up, and said so to Hawks. He responded that she was forgetting the death-row interview scene she would play with Qualen as Earl Williams. “It’s gonna be so quiet, so silent,” said Hawks. The scene is indeed a major shift, and it wasn’t in the original play or movie. Hildy lights a cigarette, hands it to Williams, and apologizes for the lipstick; he holds it for a second, admits he doesn’t smoke, and hands it back, while all the while she is gently trying to figure out how this rabbity little soul wound up shooting a cop.

But the most striking instance of hush amid chaos comes shortly after, when Mollie Malloy, played by Helen Mack in the only dead-straight performance in the picture, comes into the pressroom to berate the reporters. She took in Williams one night out of pity, and from this they spun a few days of leering fiction: “I never said I loved Earl and wanted to marry him on the gallows. You made that up.” Here is the underside of reporters’ callousness; their mockery isn’t funny when it’s turned on this sad woman. As Mollie approaches hysterics, Hildy gently leads her out of the room, which falls silent, in the longest, quietest shot of the picture, interrupted only by a call for Hildy, which is put on hold. Hildy returns at last, and holds a pose in the door for a moment, to get their attention. Then she says—with rue, not nastiness—“Gentlemen of the press.”

It’s one of the moments that show that Hildy’s femininity is an asset, not a liability. Tough as she is, she has an emotional intelligence that the boys in the back room lack. What’s more, they know it, and they respect her for it. The movie also slows down for a moment as they read her interview with Williams, and for their reaction: “I ask you, can that girl write an interview?”

Midway through His Girl Friday, an enraged Hildy calls Walter from the pressroom, threatens to hammer on his “monkey skull till it rings like a Chinese gong,” rips up the interview her colleagues were just admiring, and yanks the phone cord out of its socket. She throws on her coat and turns to make a grand exit speech to her colleagues, when suddenly sirens sound, guns fire, and klieg lights bounce around the room.

The boys leap to their phones, and here the cutting matches the electric pace: “Hello! Hurry up, this is important . . . Earl Williams just escaped . . . Jailbreak! . . . Williams went over the wall! . . . I don’t know anything yet . . . Call you back!” One by one, they race by Hildy, whose head whips back and forth as she watches them like she’s at the track, until, finally, she can’t stand it anymore. She leaps to the table, calls Walter, yelling, “Don’t worry, I’m on it!” Off she goes, Hawks’s camera held steady on Russell’s back as she pounds down the hall, high heels be damned, about to prove once more that she’s the best newspaperman of them all.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2017 edition of His Girl Friday.