The Long Shadow of Gilda

Gilda starts in a dark void, the camera then moving up through the blackness into a crowded room, dice rolling across the floorboards. In a crouch, greasy hair falling in his face, Glenn Ford, as gambler Johnny Farrell, introduces the dirty, suspicious atmosphere of Charles Vidor’s 1946 film. Although Gilda shows Johnny’s quick rise to casino manager, trading his messy duds for a tuxedo, the crouch on the floor hovers around the character like an afterimage, picked up on by everyone, especially the washroom attendant who clocks Johnny as a “peasant.” Gilda, for all its fantasy glamour and its supposedly happy ending, never shrugs off that grubby opening, nor the void that continually threatens to drown everything.

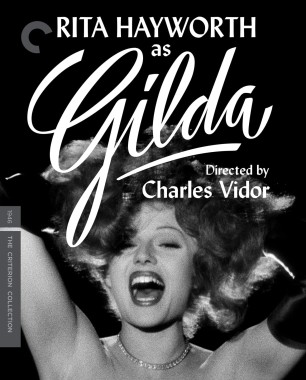

Although Gilda was a smash hit with audiences and made Rita Hayworth a superstar, reviews from American critics at the time were only mildly positive to lukewarm. French critics, however, soon recognized that it was part of something important happening in American film. In the summer of 1946, after being cut off from American releases during the Second World War, French audiences were treated to a stream of stateside films from the previous years to the current one, including The Maltese Falcon; This Gun for Hire; Laura; Murder, My Sweet; Double Indemnity; The Woman in the Window; The Killers; The Big Sleep; and Gilda. These films brought with them a sense of something new in the air, a mood cynical, pessimistic, and thrilling. In their 1955 book, A Panorama of American Film Noir (1941–1953), Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton would try to describe the impact of seeing all these films at once: “With little news of Hollywood production during the war, living on the memory of Wyler, of Ford and Capra, ignorant even of the newest luminaries in the directorial ranks, French critics could not fully absorb this sudden revelation.”

Who could, seeing all those films at once? They were dark and sexually frank, with a style reminiscent of German expressionism. But while French critics were raving about Gilda, Bosley Crowther’s New York Times review sounded utterly baffled: “The details are so mysterious and so foggily laced through the film that they serve no artistic purpose, other than to confuse things still more.”

He’s right. Gilda is confusing. In it, hatred is more powerful (and sexier) than love. Gilda’s husband of one or two days, Ballin Mundson (played with a beautiful and disturbing mix of insecurity, impotence, and deadpan calculation by George Macready), confesses to Gilda, “Hate can be a very exciting emotion. Very exciting. Haven’t you noticed that?” Later, Gilda echoes those exact words into Johnny’s ear, and her arousal is palpable. Gilda is not meant to be clear. It is meant to plunge the audience into an atmosphere so emotionally claustrophobic that even Johnny’s voice-over can’t provide escape or enlightenment. In fact, his voice-over drops away in the final section of the film, so that Johnny’s feelings about Gilda in the last scenes are never revealed. Most noir voice-overs provide backstory and explanation. Not Johnny’s. There are some things that are buried too deep. The only characters in the film who have any perspective are the washroom attendant and the police detective. The leads have none.

Gilda is a destabilized hybrid of polished studio musical and pitch-black noir. The film looks both backward, to The Shanghai Gesture, Casablanca, and To Have and Have Not, and forward, to the sexually and politically paranoid films of later noir. There is a cadre of eccentrics as well as a couple of wandering leftover Nazis. There’s a “tungsten cartel” that recalls the uranium ore in the contemporaneous Notorious and is equally irrelevant to the story. Gilda also features an “exotic” setting, like Notorious and those earlier films, with characters who may not actually be allowed to return home. The docks and casinos of Argentina in Gilda represent the end of the line. The mood is violent, sexual, chaotic. Hayworth is often shot in complete darkness, not even a bar of light across her eyes. Characters’ shadows on the walls are so elongated that they appear to be detached sentient beings. In one scene, Ballin stands in the foreground, a looming black shape on the right of the frame, with Johnny and Gilda fully lit across the foyer. The scene ends with Ballin turning his head, a flat black silhouette superimposed on the scenery beyond. These are psychosexual noir effects, tipping the studio movie into the muck.

Unlike Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity or Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice, Hayworth here is no femme fatale. Gilda is a pawn between two men who seem more interested in each other than in her. The script, adapted by Jo Eisinger and written by Marion Parsonnet, based on a story by E. A. Ellington, is explicit on that point. There’s Ballin’s phallic cane/sword named his “little friend”; at one point, Ballin says, “Wait for me here, Johnny. I’ll need both my little friends tonight.” In another scene, Ballin slowly climbs the staircase, with Johnny a couple of steps behind, their black-tuxedoed figures stark against the white marble—and it looks like an ascent to the bedroom. Johnny worries obsessively over Ballin, and when Johnny marries Gilda, following Ballin’s “death,” Johnny sneers in voice-over, “She wasn’t faithful to him when he was alive. But she would be faithful to him when he was dead.” It’s psychotic. Ford and Hayworth have a scene by the elevator after her performance of “Put the Blame on Mame” that is shocking, hatred (indistinguishable from lust) seething from both sides. Gilda is trapped by the men who desire her, use her, punish her.

The ending, with Johnny and Gilda exiting together, is a holdover from the days of the cathartic “The End” of musicals, but it leaves an uneasy impression, similar to the final scene in Notorious. In neither ending does it feel like “love has triumphed.” It’s more like a criminal getaway. That confusion, so rich, so tormented, so surreal and true, is a huge part of Gilda’s fascination, its enduring draw.

The auteur theory often ignores directors like Charles Vidor because he didn’t “mark” a picture with a certain style. He directed according to the demands of whatever story he was hired to tell, and he did it all: horror films, screwball comedies, crime dramas, musicals. But his fluidity is nothing to dismiss. It is the bread and butter of the movie industry. Vidor was especially excellent with actors, directing three to Academy Award nominations: Cornel Wilde in 1945’s A Song to Remember, James Cagney in 1955’s Love Me or Leave Me (with Doris Day giving an equally bravura performance), and Vittorio De Sica in 1957’s A Farewell to Arms. He had a simple, clear style, most apparent in dance numbers. Gene Kelly dancing with his reflection in Cover Girl (1944) is one of the best examples; watch how that camera moves. Vidor had a rocky relationship with authority figures, in particular Columbia studio head Harry Cohn, whom Vidor eventually sued for excessive profanity (Vidor lost). He also had a very hard time with producer David O. Selznick while shooting A Farewell to Arms—Selznick’s famous memos, written almost daily to Vidor, betray increasing irritation with the director. But Vidor’s work with actors speaks for itself. The fact that so many already good actors gave great performances under his direction is one of his most impressive legacies.

Vidor directed Rita Hayworth in four films: The Lady in Question (1940), Cover Girl, Gilda, and The Loves of Carmen (1948). This period also represents Hayworth’s breakthrough from ingenue and promising leading lady to spitfire bombshell superstar. Interestingly, Gilda cinematographer Rudolph Maté also worked with Hayworth on several films during this time: Cover Girl, Tonight and Every Night (1945), and, on the heels of Gilda, Orson Welles’s surreal masterpiece The Lady from Shanghai (1947), in which Hayworth, a platinum-blond femme fatale, ends up in a house of mirrors, her multiple reflections shattering to bits. Both Vidor and Maté knew how to position Hayworth, how to frame her face, how to set her up powerfully in the dance numbers, and how to capture her unique energy. These are all very different films, with varying moods and styles, and Hayworth easily transitioned from one to the next. It was as if Vidor and Maté both knew what she had in her, and they were ready to capture it.

Hayworth’s dancing got her into Hollywood, after a rough childhood as practically an indentured servant of her taskmaster dancer father. Howard Hawks put her in Only Angels Have Wings in 1939, as a bombshell who could keep up with the boys. The role showed Hayworth’s toughness and unforced sexiness, a killer combo that would be so apparent later on in Gilda. But mainly, Hayworth found her place in musicals. Fred Astaire admitted in later life that she was his favorite dance partner. Her dancing was not ethereal or floating, like a lot of her female contemporaries—Cyd Charisse, Ginger Rogers, Ann Miller. Commonly described as “explosive,” Hayworth’s style was that of a gypsy hoofer who had been dancing since she was three years old. She was hearty, earthy, grounded. Hayworth was both thoroughbred and workhorse.

In Gilda, Hayworth was able to use her dancing in a totally different way than she had before. The comparison is startling. Some of the credit for this must go to Vidor (as well as to the gowns designed for her by Jean Louis, one white and one black, for the two numbers, “Amada mio” and “Put the Blame on Mame”), but the majority of it belongs to Hayworth herself. In both numbers, her gestures, hip bumps, knowing smile, and tousled, wild hair make an electric impression to this day. She had already done all of that with Kelly and Astaire earlier, but in Gilda she pours it into a container both ferocious and desperate. There is no resemblance between the sizzling dancer performing “Put the Blame on Mame,” slowly rolling off one glove to reveal a creamy arm, and the happy, bouncing tap dancer in the opening number of You’ll Never Get Rich (1941). The musical numbers in Gilda are not a break in the action. They are the action. When “Put the Blame on Mame” ends, and Hayworth invites the men in the audience to come up onstage and take off her dress, the movie-musical illusion shatters and reality comes barreling in, ruthless and brutal. It’s an astonishing moment, the most famous moment in the film, second only to her first appearance. Hayworth understood what she was doing, and understood exactly what it was she was toppling.

Who can say where “movie magic” comes from? Sometimes the most powerful movie magic happens by accident, a film or a performance tapping into the mother lode of fantasy and dream and illusion, something all films strive for but so few achieve. There have been some carefully orchestrated careers (although few of those result in supernova-hot stardom), actors making risky choices to play “against type,” vehicles chosen to push a specific starlet to the front. However, you could not really set out to do what Gilda did for Rita Hayworth. She had a studio and a publicity department behind her, the love of American GIs for her famous pinup, but still . . . what she brought to Gilda was all her own.

The shadow of Rita Hayworth in Gilda has stretched across the culture for almost eighty years now. In 1946, the United States conducted a couple of atomic-bomb tests on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The first bomb dropped was named Gilda. In 1948, in De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, Antonio is in the process of putting up a Gilda poster when his bike is stolen. In 1982, Stephen King published Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, a novella in which Hayworth’s pinup photo hides the hole dug in the wall of a prison cell. In the 1994 film adaptation of King’s story, the prisoners gather in the mess hall to watch Gilda, and right before Hayworth first appears, Morgan Freeman says to Tim Robbins, “This is the part I really like. This is when she does that shit with her hair.” It’s not just lust on his face, but appreciation of her beauty and the joy that it brings. There are tributes, too, in Notting Hill (1999) and David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. (2001).

In a Turner Classic Movies documentary on Hayworth, a World War II veteran remembers the effect of Hayworth movies on soldiers during the war: “You can’t imagine what it is when you’re out in them islands, you think you’re gonna be dead tomorrow, and you get something like that.” That is a profound level of stardom and fan identification that few actors ever achieve.

Even people who have never seen a Rita Hayworth film are familiar with her entrance in Gilda. She doesn’t emerge from the shadows, smoking a cigarette; she isn’t discovered in a room, staring out the window. Instead, there’s an empty space in a well-lit room, and she just appears, rising up from below the frame like a siren from the rocks, flipping her hair back over her head. Many very good films don’t contain such a moment, a moment that becomes iconic in and of itself, separated from all that surrounds it. It is the star power of Hayworth at work, but also the smarts of Vidor, who chose to “present” Gilda as exploding up from beneath the screen, filling the empty space. Just as Johnny emerges from the black void in the opening scene, Gilda emerges from a void, too, and that’s where the image gets its charge. First, she is not there. And then, in a whoosh, she is there.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2016 edition of Gilda.