Heat Stroke: Crazed Fruit and Japanese Cinema’s Season in the Sun

Then film critic and soon-to-be figurehead of the 1960s Japanese new wave Nagisa Oshima saw it as a portent of the future, famously observing that “in the sound of the girl’s skirt being ripped . . . sensitive people could hear the wails of a seagull heralding a new age in Japanese cinema.” Composer, free improviser, and connoisseur of all things outré Asian John Zorn honored its lust-racked stars—savage-innocent Masahiko Tsugawa, insect girl Mie Kitahara, and superstar Yujiro Ishihara—with a racy, delicately raucous chamber piece, written for string quartet, turntables, and voice, entitled “Forbidden Fruit.” And a third someone, their name long since forgotten, once hoped to market it to American audiences under the title Juvenile Jungle—a bit of grind-house-geared marketing hyperbole whose only lasting effect was that it remained engraved upon what was, until now, the only English-subtitled print still known to exist.

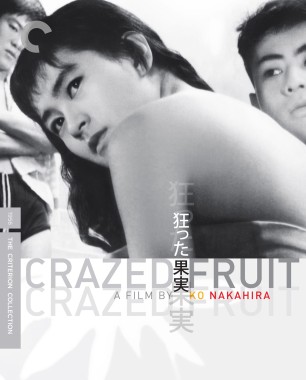

What it is, of course, is Crazed Fruit (Kurutta kajitsu), director Ko Nakahira’s 1956 Nikkatsu Studio youth flick—the epochal taiyozoku (Sun Tribe) classic that helped transform postwar Japanese cinema. An emotionally and aesthetically roughed-up program picture—so stained with hormonal sea spray and ideological lip sweat that it outraged Japanese housewives and educators; chal-lenged the intimate relationship between Eirin, the Japanese film censorship board, and the film studios it was mandated to monitor; and seismically shock-started the tsunami of the Japanese new wave—Crazed Fruit wasn’t just a storm warning of new and choppy times. This rock-around-the-docks antiromance—full of “Yankee Go Home!” invective, intellectually adolescent ancestor loathing, hormonally overloaded misogyny, and a speedboat determination to slice through the stagnant waste waters of traditional Japanese cinema’s brotherly, motherly, and every-sort-of-otherly love—was moviemaking as killer riptide, cinema as all-consuming undertow. From its opening shot—sixteen-year-old Tsugawa, his hair cropped nihilistically short and his eyes psychotically scanning the horizon, slicing through waters as black as blood in the moonlight, at the helm of a switchblade-sleek power skiff christened the Sun-Season—to its climactic whirlpool of retribution and oblivion, Crazed Fruit emits a scream of rudderless abandon as deafening as that speedboat’s Evinrude roar.

While elsewhere on the back lot Seijun Suzuki was busy directing the first films of his legendary career, Nikkatsu neophyte Nakahira—who’d made but a single movie for the studio (something called Beef-Shop Frankie), just a few months earlier—shot Crazed Fruit, in what the accountants at the conveyor-belt-minded entertainment tur-bine no doubt regarded as an unconscionably leisurely seventeen days. With Nikkatsu’s Season of the Sun and Daiei’s Kon Ichikawa–directed follow-up, Punishment Room, it was the third taiyozoku film released that year, all of them adapted from stories by Shintaro Ishihara, the twenty-three-year-old winner of the 1956 Akutagawa literary prize. The outspoken Ishihara—who would later write the ultranationalist The Japan That Can Say No and become the popular, albeit contentious, multiterm gov-ernor of Tokyo (a position he still holds)—claimed that he hadn’t so much invented a new genre with his taiyozoku tales of affluent kids set loose in the upward flux of their country’s postwar “economic miracle” as documented the youth culture that he and his twenty-one-year-old brother, Yujiro, had experienced from within. But while critics and audiences had generally dismissed those first two taiyozoku films as run-of-the-mill exploitation, critic Tadao Sato—whose first volume of essays, Japanese Film, had coincidentally won the movie magazine Kinema Jumpo’s book award that year—agreed with Oshima, and the sentiments of the moviegoing majority, when he wrote that only Crazed Fruit had “captured the sense of intoxication of the original, and expressed Ishihara’s premonition that these rich youths, who had been raised without restraints, were the harbingers of an age of rapid economic growth and free sex.”

Introduced with a blurt of bawdy sax and rubber-kneed slide guitar written by Akira Kurosawa regular Masaru Sato and internationally renowned classical composer Toru Takemitsu, Crazed Fruit is the story of Natsuhisa and Haruji, two brothers on a seaside summer vacation. Older and randier, Natsuhisa (played by Shintaro Ishihara’s younger brother Yujiro, whose bowlegs, big teeth, and naturally insolent manner made him an instant star) spends most of his time with a band of similarly boredom-stricken buddies, led by the languidly magnetic Frank (Masumi Okada), an Amerasian ne’er-do-well with a top-down jalopy and a drowsy-eyed demeanor apparently decanted from Dean Martin’s wet bar. Uneager to join in on the casual circulation of good-time girls enjoyed by the rest of the crew, Haruji (Tsugawa, who would graduate to playing top pimp in Oshima’s blood-for-cosmetics anti-taiyozoku masterpiece The Sun’s Burial, some four years hence) tags along anyway, hoping to woo and win the one woman he knows will make him the envy of the others: a gorgeous if naggingly elusive gamine named Eri (Kitahara). That Haruji only manages to make Eri’s acquaintance when he pulls up to her in his motorboat, as she’s swimming alone in open waters, dangerously far from shore, sets the tone for everything to come. Mermaid or siren? The inevitably double-edged answer to the Eri question arrives when, after proclaiming the purity of her affections for Haruji, she surrenders to elder brother Natsuhisa as well—and admits that the portly American businessman she’s often seen dancing with is in fact her sugar-daddy husband from abroad. Imagine a Rebel Without a Cause in which Sal Mineo is the last man standing, vengefully gloating over the corpses of James Dean and Natalie Wood after their faux-parental passions disrupt the Oedipal unreason of his greasy kid-stuff dreams, and the final quaff of Crazed Fruit’s bitter nectar is yours.

Though frank in its depiction of Eri’s infidelities and indiscretions, Crazed Fruit could scarcely be described as sexually explicit. But as film scholar Donald Richie would later point out, the cuts demanded by the Eirin censors—particularly the abrupt shortening of a shot of Natsuhisa ripping away Eri’s skirt, for which Nakahira substituted an image of the sun-stained sea, with the soft moan of Eri’s acquiescence still heard underneath—only served to heighten the movie’s suggestive salaciousness. Outraged that college students should be depicted as nihilistic, promiscuous, and potentially psychotic, groups of housewives and the PTA organized protests and succeeded in having the film restricted for viewers over the age of eighteen in some cities. And yet, for all the civic-minded hand-wringing that the taiyozoku books and movies were met with at the time, the youth culture they were condemned for depicting, and perhaps even celebrating, was in actuality more a figment of the cultural imagination than a real-life after-effect of postwar social reforms. Though a 1956 issue of Time quoted one “twenty-one-year-old farm boy” as opining that “Ishihara writes truly what we, the younger generation, are looking for,” the magazine was quick to editorialize against such idol worship, observing that, “for Ishihara himself, the truth was not so simple. A conscientious professional who lives quietly with a pretty, kimono-clad young wife, in the ancient tradition of his ancestors, the idol of the Sun Tribers tempers his cynicism with hard work: ‘As an author, I’ve got to sleep with my generation like a prostitute, but I’ve also got to climb out of bed occasionally and try to get one step ahead of it.’”

Ishihara was being modest. Though the privileges of the brothers’ personal background were echoed in the literary and filmic genre they helped to create—a wealthy father who died when they were young, boyhoods spent boating near their home along the Zushi coast, a sense of economic independence that bred a calculated attitude of mannered indifference and narcissistic cool—that was scarcely the sort of lifestyle and luxury available to Japanese teenagers at large. Never mind the nightclubs and the water skis: as film critic Mark Schilling has pointed out, even as late as 1959, only one Japanese person in 131 had the means to afford so much as a car. An irrational enlargement of postwar future-dread on par with Godzilla—that other terror-from-the-tidal-chaos touchstone of the period, released just two years before—Crazed Fruit, and the taiyozoku phenomenon as a whole, proved largely an exercise in Bunraku puppet drama, with outrageously oversize id monsters posed against dream backdrops as familiar to most young Japanese as they were out of reach.

For all its libidinal exertions and lurid intimations of sociological decay, by today’s standards Crazed Fruit appears almost startlingly regressive—as culturally reactionary as The Searchers, as absurdly postadolescent as The Girl Can’t Help It, and as morally adamantine as The Ten Commandments, to name but three of its Hollywood contemporaries. And though it cannily exploited the insouciant demeanor and brusque manner of speaking that Yujiro Ishihara insisted were merely a reflection of his own everyday affect—and that resulted in his instant celebrity and career-long popularity—Crazed Fruit ultimately did as much to domesticate Yujiro’s rebel-rebel persona as it did to create and cash in on it, just as another of its California cousins, Love Me Tender, had done in 1956, with the hillbilly hepcat persona of its cine-debutant, Elvis Presley. Yujiro may have burst onto the screen like a bandy-legged Brando, but—after sneaking off to the States and marrying costar Kitahara, in 1959—he retreated from what his fans felt was the far-too-Western remorselessness of Crazed Fruit’s Natsuhisa, and concentrated on roles as underwritten by con-servatism as the career-making baritone that he, like Presley, had borrowed from Bing. And while big brother Shintaro would later add to his political notoriety by suggesting that the Rape of Nanking was in fact a Chinese fabrication, director Nakahira rapidly faded from the limelight, eventually crutching up his faltering film career by emigrating to Hong Kong, where, under contract to Shaw Brothers studios, he adopted the screen name Yang Shuxi and, in 1969, remade Crazed Fruit as the long-forgotten potboiler Summer Heat, starring Shaw Eurasian ingenue Jenny Hu. Having burned so very brightly, the once so vibrant Sun Tribe quickly went dark, a momentary revolution no more lasting than a case of summer love. What remains, however, is the movie you’re now holding, and the next time Terry Jacks starts in with all that malarkey about “We had joy, we had fun,” feel free to swat him in the face with it. Crazed Fruit is the only memory anyone ought to be singing about from that extraordinary season in the sun.