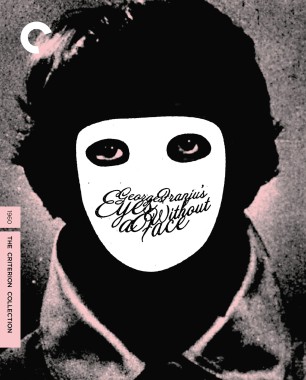

Eyes Without a Face: The Unreal Reality

There is a moment in Eyes Without a Face—you’ll know it when you see it—when, according to L’express, “the spectators dropped like flies.” At the 1960 Edinburgh Film Festival, seven viewers actually fainted, prompting director Georges Franju to crow undiplomatically, “Now I know why Scotsmen wear skirts.” The movie scandalized viewers so much, the outraged French critical establishment tried to deny that the film even existed. The only English reviewer to admit that she liked it was nearly fired.

How had it come to this?

In the later years of the 1950s, films like Terence Fisher’s The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Horror of Dracula (1958) had substantially increased the level of suspense, sexuality, and gore that people could expect from thrillers. French cineastes ate these gothic Technicolor visions up, demonstrating a hungry and largely untapped market for horror movies in the country. In 1955, Henri-Georges Clouzot pulled no punches in terrorizing filmgoers with Diabolique, but no filmmaker in France had yet attempted a full-blooded horror picture of the kind being made so profitably in England and America. Jules Borkon set out to be the first producer to cross that Rubicon.

Although there had been a rich and vibrant tradition of French fantasy, the prevailing critical opinion held that the horror genre was fundamentally at odds with the intrinsically artistic nature of the nation’s cinema. Critics desperately tied themselves into knots to reconcile Eyes Without a Face with their preconceived notions of what good French cinema was supposed to be. Of course, this dilemma vanished if you agreed that horror filmmaking was a valid exercise in itself, that engaging an audience’s fear was as legitimate as manipulating any other emotion—but few critics could bring themselves to admit that. Writing for Cahiers du cinéma, Michel Delahaye argued that Eyes Without a Face must actually be a film noir masquerading as horror, since it was beyond question that no serious artist would debase himself by making a horror picture.

And Georges Franju was a serious artist. He was already notorious for his short Blood of the Beasts (1949), which combines footage of animal slaughterhouses with shots of children at play—a collage of everyday images, some of them secretive and sickening but all of them true. He was at work on his first feature, a drama about insane asylums, Head Against the Wall (1959), as the Eyes Without a Face project percolated—but Franju’s status depended on more than just his filmmaking experience. In 1936, along with Henri Langlois, Franju had founded the Cinémathèque française, the most enduring and influential institution in French film culture. Franju operated the Cinémathèque as a glorified film club—at heart, he was a fan. Whereas some of his contemporaries, such as François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Claude Chabrol, were film critics who picked up cameras to put their theories into practice, Franju was ever apart from the New Wave. He was just a film buff—steeped in a passion for pulp.

Most French directors would have been insulted to be offered this job, but Franju, having grown up on the films of silent-era fantasists George Méliès and Louis Feuillade, relished the chance to make his own contribution to the genre of the fantastique. Since that genre now included Peter Cushing’s Dr. Frankenstein casually wiping a blood-stained palm on his jacket, Eyes Without a Face would have to include blood. Just not, Borkon cautioned, too much blood—don’t want to worry the French censors. Oh, and by the way, Borkon added, don’t show animals being tortured—that upsets the British. Also, no mad scientists, since the Germans are touchy about the whole Nazi-doctor thing.

This Borkon said while handing Franju a project about a mad doctor who tortures animals while cutting off women’s faces.

The producer had bought the rights to a novel by Jean Redon, which in another time might have been a fine vehicle for Bela Lugosi. To temper the B-movie histrionics, Franju brought in the writing team of Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. Fresh from—and flush from—their success working with Clouzot on Diabolique and with Alfred Hitchcock on Vertigo, Boileau-Narcejac (their collaboration was so tight their names became fused together as one) brought an impressive pedigree to an increasingly prestigious venture. They kept the basic sequence of events from the book but shifted the emphasis away from Dr. Génessier and onto his disfigured daughter, Christiane. As played by Pierre Brasseur, Génessier would still be the prime mover of the story. His actions and choices drive the film, but all his crimes are caused—indirectly, unwittingly, even unwillingly—by Christiane.

It was hardly the kind of role likely to attract a major star—Christiane, like everyone else in the film, has little dialogue, and her face is concealed. Yet this fragile, doomed creature is the true star of the movie, the eyes without a face of the title. Edith Scob had worked with Franju on Head Against the Wall in a small but memorable role, and the two became a team: Franju cast her in four more films after this one. Yes, Scob is beautiful and vulnerable, but beyond that she has an intangible air of mystery about her. Franju said of her: “She is a magic person. She gives the unreal reality.”

Motivated by guilt and love, Dr. Génessier’s obsessive actions became more understandable. He became a very human monster, a breed apart from the Dr. Frankenstein figure the Germans allegedly found objectionable. This was how Franju skirted Borkon’s restrictions: by seeing them not as barriers but as hurdles that should inspire him to leap even higher. To his surrealist’s eye, true art came from confronting taboos.

The key was in finding the right tone. Feuillade’s genius was in his affectless, matter-of-fact depictions of the wildest, pulpiest lunacy. Franju inverted the equation, while still juxtaposing the fantastique with the mundane, the impossible with the everyday. Franju was on record as being “led to give documentary realism the appearance of fiction.” Or, to put it another way: “Kafka becomes terrifying from the moment it is documentary. In documentary, I work the other way round.” Any way you slice it, Franju was fixated on the seam between actuality and fantasy.

It would be up to his gifted cinematographer, Eugen Schüfftan, to render Franju’s visions of fairy-tale realism in luminous silver. As a veteran of the films of Fritz Lang, Abel Gance, G. W. Pabst, and Edgar G. Ulmer, Schüfftan was the ideal choice to illustrate Franju’s nightmares.

Since it was designed to pass through the European censors, Eyes Without a Face really faced troubles only in America. Dubbed into English and retitled The Horror Chamber of Dr. Faustus, the film wound up on a double bill with The Manster (1959), a more typically exploitative monster flick. The American distributor at least recognized the unique qualities of their find, and played up its art-house credentials. “A ghastly elegance that suggests Tennessee Williams,” boasted the ads. One optical zoom and a discreet fade to black later, and the most objectionable excesses of the face-removal scene were safely hidden from impressionable American teenagers. The biggest cut, though, was not in the violent content but in the film’s humanity: a scene of Génessier lovingly caring for a small child at his clinic was snipped from U.S. prints. Blood and gore, fine, but Franju crossed the line when he gave his villain a sympathetic side.

This long-overdue release restores Franju’s unexpurgated cut. Decades of horror films that have followed in its footsteps have necessarily blunted the force of its shock scenes, but nothing can conceal the power of its ugly poetry. Franju deftly balances fantasy and realism, clinical detachment and operatic emotion, beauty and pain, all presided over by Scob’s haunting, haunted eyes.

This piece originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2004 DVD release of Eyes Without a Face.