Stories of Floating Weeds

"Floating weeds, drifting down the leisurely river of our lives,” has long been a favored metaphor in Japanese prose and poetry. This plant, the ukigusa (duckweed in English), floating aimlessly, carried by stronger currents, is seen as emblematic of our own journey. And sometimes this identity is made explicit—in the lives of traveling actors, for example.

It is with these that Yasujiro Ozu’s 1934 A Story of Floating Weeds (Ukigusa Monogatari) and his 1959 Floating Weeds (Ukigusa) are concerned. Both films revolve around a recurring character type who appears in several other Ozu films: the lovable ne-er-do-well usually called “Kihachi” (though in the 1959 version he is called Komajuro). Here, we find Kihachi as the leader of an itinerant dramatic troupe, returning to a small town where he has a lover by whom he has a now-grown son. The boy does not know this but the leading lady of the troupe—the boss’ mistress—finds out and plans her revenge. Though both parents had hoped or some permanence, a family life, the end of both pictures finds the troupe leader again on the road. He continues to drift down the river and Ozu’s major theme—the dissolution of the family—is again demonstrated.

1934’s A Story of Floating Weeds was among Ozu’s most successful films, both critically and financially, and Ozu sometimes mentioned an inclination to remake it. He had the opportunity to do so when, in 1959, he was asked by Daiei Studios to make a film for them. Ozu’s contract with Shochiku Studios, his home company, called for a film a year and, because the director was a slow worker, that usually left no time for other labor. That year, however, he had finished Good Morning (Ohayo) in the spring, and that left the rest of the year free.

Adapting earlier work was not unusual for Ozu. Late Autumn (Akibiyori, 1960), for example, is an adaptation of 1949’s Late Spring (Banshun)—with the same actress playing the daughter in the earlier picture and the parent in the later. There are resemblances among other Ozu films as well: Good Morning and the 1932 I was Born, But… (Umarete wa mita keredo), for example.

Given the similarities of Ozu’s films, such adaptation is not surprising. The director thought of his stories as a means of creating characters rather than making plots. He was more interested in who his people were than in what they did. Remaking, in a way, meant revisiting. Perhaps that is the reason he sometimes referred to himself as a “tofu-maker,” able to make all varieties but unable to make anything else.

Though Ozu never mentioned the similarity of Good Morning and Late Autumn to the earlier pictures, he himself called Floating Weeds a remake. “Many years ago I made a silent version of this film. Now I wanted to make it again up in the snow country of Hokuriku [the earlier version was located in Kamisuwa, central Japan], so I wrote this new script with Noda [Kogo Noda, his coscriptwriter]…but that year there wasn’t much snow, so I couldn’t use the locations I had in mind in Takado and Sado.”

Consequently, he shot the exteriors in an entirely different location: the island of Shijima, along the Wakayama Kii Peninsula. This radical change of venue, however, occasioned very little change in the script itself—though the lightly revised version was originally entitled The Ham Actor (Daikon Yakusha).

There are few major differences between the 1934 and 1959 versions, and both are consequently faithful to the plot of the American film that is said to have inspired the original script. This was The Barker, a 1928 George Fitzmaurice picture about a traveling carnival which had proved popular in Japan. The structure of Ozu’s two versions is, however, somewhat different from that then current in Hollywood. The use of ellipsis, for example, exemplifies this difference.

The opening sequence in Ozu’s 1934 version shows the troupe of traveling players arriving at the station. The shot of the last member leaving the train is followed by a shot of two advertising banners, another showing a poster for their show, an intertitle that reads: “Going to the show tonight?,” and a shot of a man having his hair cut in the barber shop.

Film historian David Bordwell has described the continuity of this sequence in the following manner, indicating the elliptical manner of its construction: “The man who asks the question and is having his hair cut is an actor from the troupe; a scene in the barbershop follows, and we are left wondering about the banners that began the sequence. Later they are established as being outside the theater; they precede a number of scenes that take place in the theater and are never shown outside this context again. In this early sequence they evidently indicate that the troupe has established itself in the theater.” In this manner Ozu typically uses narrative ellipsis, giving the spectator just enough information to allow him to make sense of the actions, but no more. Perhaps one of the reasons for the fascination of the Ozu film is that the spectator is so often called upon to bridge the ellipsis, to create a connection that the director deliberately left out, to contribute and hence to understand.

Certainly Ozu found no way to improve the construction of the earlier film. The 1959 version of the film uses the same continuity. The opening shots—railway station and port—are almost identical. The arrival of the train and the arrival of the boat are treated in a similar fashion. Characters complain of the rain in the earlier version and of the heat in the later, but otherwise the dialogue is the same.

Likewise, the films share many of the same sequences and compositions, as well as many of the same types of characters. These are often strikingly similar physical types, though only one actor is in both films: Koji (Hideo) Mitsui plays the son in A Story of Floating Weeds and the thieving actor in the Floating Weeds. In both films there is the same argument-in-the-rain sequence, just as much smoking (in 1934 a sure indicator of bad female character), the same final scene in the railway station, and the same final shot of the disappearing train.

Such close similarities would indicate that Ozu had discovered in 1934 the best way to tell his story and saw no reason to change much in 1959. Some Japanese critics find in A Story of Floating Weeds a new mastery of narrative and have said that the film heralds a new maturity in the Ozu style. Certainly once the director had discovered the effectiveness of any of his narrative ploys, he then seldom failed to include them in his later pictures.

When he was making the earlier film, Ozu was in the process of forming his mature style—the famous invariable camera position, just up off the tatami, its refusal to chase after the actors (the dolly) or even turn its head (the pan); the well-known lack of punctuation; no fades or dissolves, just the straight cut; the invariable mosaic construction of the story; the refusal of plot in any melodramatic sense; whole sections of the story omitted in ellipses—all of these attributes creating a world in which every image counts, all details contribute, and whole sections of continuity can be elided. Every image can be made to vibrate with an integrity which has always had but which we have, through habit, lost the ability to see.

Bordwell has pointed out that this logic of Ozu’s camera and character placement was first seen in the 1934 film and that the discernment of the later films “is the same in A Story of Floating Weeds.” Further, that in the 1934 film “the ideological gravity of Ozu’s material weighs down those qualities of self-conscious playfulness that contrasts so fruitfully with stylistic rigor.” Though Ozu had made films about the eroding family before this one, it had never been a major theme, nor had it made demands to stop smiling and seriously regard the loss. To notice this, however, is not to criticize Ozu. He had his reasons. He who called I Was Born, But… a dark film was interested in comedy only when it was necessary. It was not necessary in A Story of Floating Weeds. Consequently we can see, unadorned as it were, some of Ozu’s most interesting stylistic constructions. It is as though the lack of a deliberate humor in this film (in contrast to that of, say, Passing Fancy [Dekigokoro, 1933]) make the director’s stylistic constructions more explicit.

His use of object-as-transition is seen already in perfect form in the A Story of Floating Weeds, and he never later found any reason to vary this successful technique. In the film, the son of the itinerant actor rides a bicycle. This vehicle becomes a pivot for transitions throughout the film. The first occurs when he is talking with the girl who will seduce him: cut to the bicycle on its stand at home; he is talking with his mother. The second is composed of a scene in the house: bicycle still on its stand; cut to the boy and girl without the bicycle by the railway track. The third occurs after the boy has run off with the girl—the bicycle at home as before, the boy’s empty desk, mother worried. The bicycle makes its final appearance at the end of the film. The vehicle is now in another room, and the room is dark. The implication is that the boy’s bicycling days are over and he has grown up.

There are, then, many more similarities than differences between the two films. At the same time there are occasional variances. In 1959, Ozu could show things he couldn’t in 1934. In Floating Weeds there is a hotel scene: the son and the showgirl have slept together; in A Story of Floating Weeds we can only surmise this.

Mainly, however, the differences between the two films are in tone. There are various reasons for this. One was that Ozu was working at a new studio for the first time. The Daiei house style was deliberately bright and the chosen audience was young people looking for novelty. In addition, while domestic drama was a major staple at Ozu’s home studio Shochiku, it was not a genre associated with Daiei.

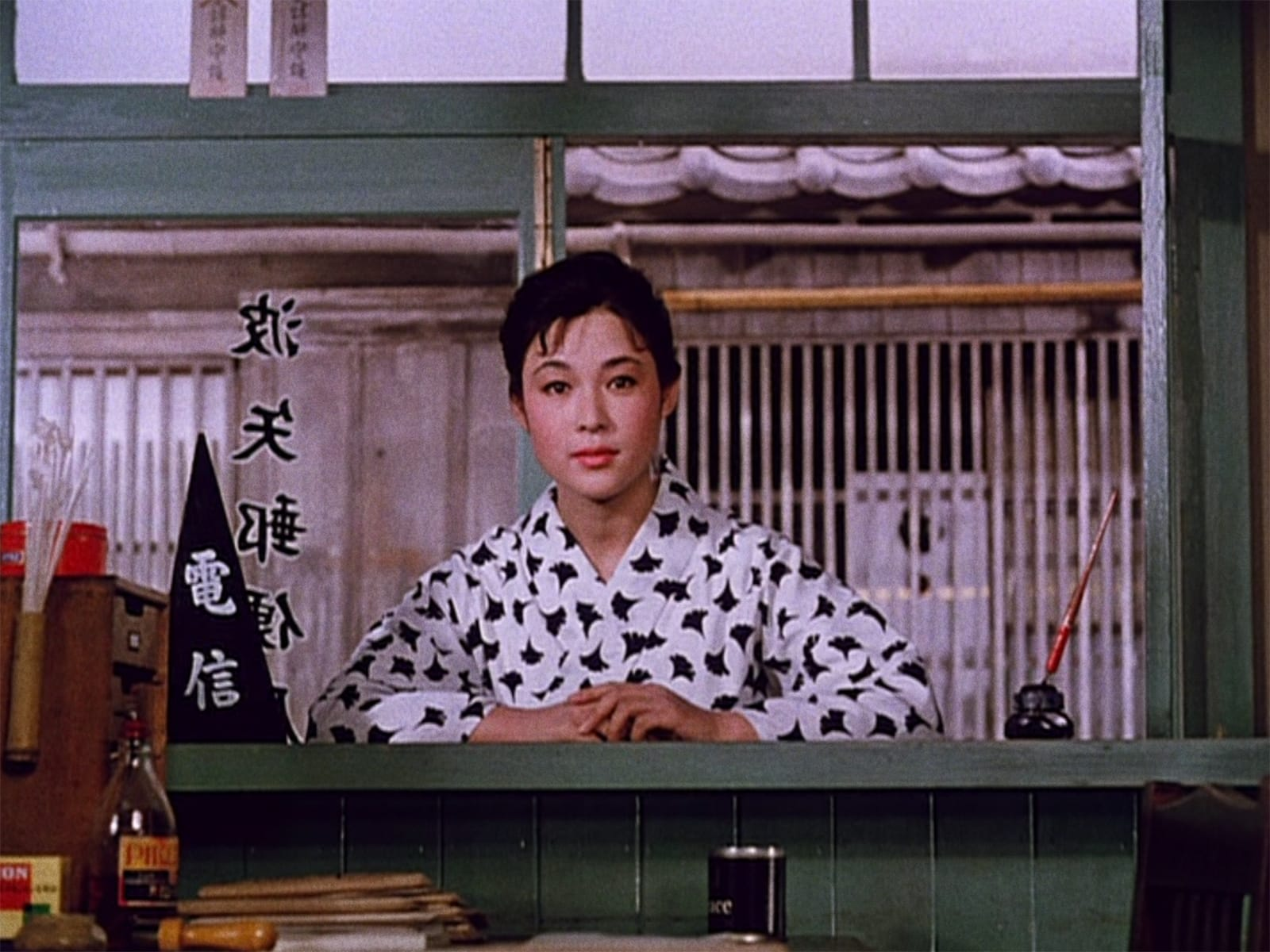

A new studio also meant a new staff and new actors. The Kihachi character, originally played by Takeshi Sakamoto (who created it in Passing Fancy), was now played by the eminent Kabuki star, Ganjiro Nakamura—a fine actor, later cast by Ozu in End of Summer (Kohayagawa-ke no Aki, 1961)—but nothing remotely like the Kihachi type.

The faithful wife in Floating Weeds was played by Haruko Sugimura, familiar to Ozu audiences from her performances in Early Summer (Bakushu, 1951) and Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, 1953). A noted stage actress who always experienced difficulty suppressing her style sufficiently for Ozu’s purposes, she suggests little of the despair of Choko Iida in the 1934 version. One result of this is that Floating Weeds seems the lighter film, enlivened by color and lacking tragic implications.

The son in Floating Weeds was played by Hiroshi Kawaguchi, a rather wooden young actor but the son of one of the most important writer-producers at Daiei. The secondary theme of actor-and-son is rendered almost invisible in the later version because Tokkan Kozo (the lively and mischievous little boy in the 1934 version) was now grown up and the only child available was the far more ordinary Masahiko Shimizu, who had appeared in a number of Ozu films, including Good Morning. Indeed, all the characters seem more prosaic in the 1959 film.

Another reason for the tonal differences between the two films is that the Daiei Floating Weeds is in color and the color is utilized in a manner different from Ozu’s Shochiku color films, Equinox Flower (Higanbana, 1958) and Good Morning. There the color is somewhat sober, in line perhaps with Ozu’s original suspicion that color photography could not be controlled as rigidly as could black-and-white.

At Daiei, however, the director was working with a master photographer in Kazuo Miyagawa, a man who used color in a more dramatic fashion, as in the later films of Kenji Mizoguchi and Kon Ichikawa. In Floating Weeds, he created the most pictorially beautiful of all of Ozu’s pictures. At the same time, he created something brighter and in a way lighter than the Shochiku Ozu films.

CinemaScope, or Ozu’s reaction to it, also played a part in the look of the 1959 film. Though the director finally gave into color, he never did to widescreen, a format standard by then at Daiei but one in which he once compared to toilet paper. About Floating Weeds Ozu wrote that “I wanted to have nothing to do with (Cinemascope), and consequently I shot more close-ups and used shorter shots…. This film must have more cuts in it than any other recent Japanese movie.”

But among the reasons for the differences between the pictures is not only the difference between Daiei and Shochiku, but also the quarter-century difference between 1934 and 1959—Ozu at thirty-one and Ozu at fifty-six.

The structural economy of the 1934 picture allows for little that is digressive. The economy of the 1959 film is similar. At the same time, however, there is in the later picture the feeling of relaxation—not of technique, nor of standards, but of attitude.

The main difference is internal. The earlier version seems the more bitter of the two. Toward the end of his life, Ozu mellowed, and one does not, for example, see or feel in Floating Weeds the pain of the once-again abandoned mother. To be sure, Haruko Sugimura is by no means happy about further betrayal, but she has become philosophical. Choku Iida in A Story of Floating Weeds shows us a bleak despair rarely seen in Ozu’s more expansive later work. In 1934, Ozu felt deeply and personally the wrong that life inflicts. Twenty-five years later, he felt just as deeply, but perhaps less personally.