Love on the Run: Past and Future Selves

While making Love on the Run (1979), François Truffaut knew that it would be the end of the Antoine Doinel cycle. He also wanted the film to be the cycle’s recapitulation. Love on the Run prolongs Antoine’s adventures (or his “flight,” to recall the film’s French title, L’amour en fuite) in two directions: toward the past, in flashbacks to scenes from the four previous Doinel films, and toward his future with his new girlfriend, Sabine.

At this point in Antoine’s life, the arrested-adolescent routine is wearing thin. He’s getting a divorce (in anyone’s life, proof enough of having entered adulthood). Fate causes his path to collide again with that of Colette, his love object from Antoine and Colette (1962). Now a lawyer, she’s headed to the town of Draguignan, in Provence, to discuss a case she’s been offered. Antoine impulsively accompanies her part of the way.

This encounter, as far as the Doinel saga is concerned, is just one more temptation—the last?—for him to stay stuck in adolescence. But Antoine has another chance encounter—the decisive one, since it ties Love on the Run back to The 400 Blows (1959) and points toward a resolution of the central conflict of the Doinel series. This is his meeting with Monsieur Lucien, his mother’s “main” lover. Lucien gives Antoine a supreme gift. “Your mother loved you, son,” he tells Antoine. “She had a strange way of showing it, but she loved you.”

“Obviously, this ‘reconciliation’ owes much,” Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana write in their biography of Truffaut, “to Truffaut’s discovery in his mother’s archives, just after her death, of numerous documents left by her which proved a real attachment toward her son.” In the reproaches various characters aim at Antoine in Love on the Run, we can hear Truffaut reproaching himself for his resentment toward his mother. In a scene from Bed and Board (1970), preserved as a long flashback in Love on the Run, Christine tells Antoine her reservations about the novel he’s writing: “If you use art to settle accounts, it’s no longer art.” Truffaut is finished with settling old scores.

The logic of the four earlier Doinel films suggests that if Antoine is an eternal child, always seeking a replacement for his mother in the women he chases, it’s because his real mother robbed him of his childhood. For the first time in the series, Love on the Run acknowledges that (in Lucien’s words) “the fault was not entirely theirs.” The logic Truffaut asks us to believe in, if only for this film, is this: when he accepts his mother’s love, Antoine can stop running.

The Draguignan subplot, which at first seems to have little connection with the rest of Love on the Run, pushes the theme of the theft of childhood to an extreme while hinting at those areas of experience that must be skirted around if the Doinel saga is to reach its happy ending. Colette has been given the opportunity to defend a man who, persuaded that his three-year-old son wasn’t his own, beat the child to death. By taking the case, Colette (who has an emotional stake in it, as a parent who lost a child) performs, in Antoine’s place, a symbolic act of forgiveness.

Truffaut’s decision to follow Colette to Draguignan lets him, and us, get away from Antoine for a while—a rare opportunity in a series that has been almost shot-by-shot centered on Jean-Pierre Léaud’s charismatic hero. Granting an independent narrative line to Colette is a sign of the uniqueness of Love on the Run in the Doinel cycle: a formal sign of maturity and one of several intimations in the film that the series is concluding. And the immense charm and energy of Marie-France Pisier’s performance as Colette, from her first appearance outside the court building to her homage to Howard Hawks’s Big Sleep bookstore scene, help keep Love on the Run enjoyable while Léaud is offscreen.

But even when the film isn’t directly concerned with Antoine, it’s still about him. Charles-Antoine, the Draguignan killer, is Antoine Doinel’s likeness and brother. In the photos we glimpse of him, he resembles Antoine. Both have young sons by estranged wives. Charles-Antoine tries to carry out the suicide that Antoine merely contemplates for his other alter ego, the hero of his second novel. Charles-Antoine is the character Antoine can’t be without violating the tone established for the Doinel films: a tragic, irredeemable figure who pushes his revolt against society to the extreme. For all Antoine’s pretense of hating life (which Sabine throws back at him), he can’t enter Charles-Antoine’s world.

Other surrogate Antoines appear during Love on the Run, such as Colette’s reluctant lover, Xavier (his “I don’t carry books with ‘love’ in their titles” sounds like a Léaud line), and the angry man in the phone booth who tears up the photo of Sabine. The torn photo, which Antoine pieces together, is itself a potent visual metaphor for the mosaic of flashbacks with which the film completes the image of Antoine. Although some detractors of Love on the Run have seen these flashbacks as a kind of “Antoine Doinel’s Greatest Hits,” their order and purposefulness give a certain intellectual tension to a film that risked coming off as too relaxed. (Editing, always a strong point in Truffaut’s films, takes on unusual importance in Love on the Run, which is edited throughout with dazzling verve.)

It’s easy to imagine a continuation of the Doinel series in which Antoine returns to his old tricks. Truffaut admitted: “I would be lying if I said Antoine Doinel succeeded in his transformation into an adult. He has not become a real adult, he is someone who has remained a child. There is a lot of childhood left in all men, but with him, it’s even more so.” The sense of the difficulty of a real assumption of adulthood gives Love on the Run an undercurrent of anguish, despite its surface lightness. Added to that is the melancholy of saying goodbye not just to Antoine Doinel but to the two momentous decades of French cinema he has come to represent. Léaud felt the sadness of this separation acutely. In a 2001 interview, he remembered the shooting of Love on the Run as a painful experience. “Personally, I would have never renounced or stopped Doinel,” Léaud said. “In any case, he is part of history.”

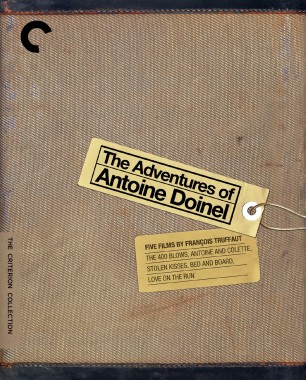

This essay was originally published in the Criterion Collection’s 2003 edition of The Adventures of Antoine Doinel.