Gray’s Anatomy: The Eyes of the Beholder

Spalding Gray was a solo performer, an author, and an actor. As he wrote in his epitaph—and who better to compose his own than a man who made art by writing and speaking incessantly about himself—“Most of all he was known for his autobiographical monologs in which he would sit onstage at a table with a glass of water and tell true stories from his life.”

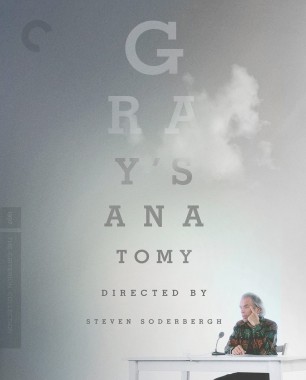

Gray was a member of the renowned experimental theater company the Wooster Group when, in the late 1970s, he conceived and performed his first monologue (he always spelled it monolog), a work in progress that became Sex and Death to the Age 14. He performed this and subsequent monologues worldwide over the course of a twenty-five-year career, and became the model for countless young performance artists. Three of his monologues were made into feature films: Swimming to Cambodia (1987), directed by Jonathan Demme; Monster in a Box (1992), by Nick Broomfield; and Gray’s Anatomy (1997), by Steven Soderbergh. Soderbergh, especially, felt a close affinity for Gray’s work; there was something about the way Gray seemed to be extremely open on the stage while at the same time watching his storytelling process from a distance that, Soderbergh has explained, paralleled his own process. After Gray’s death in 2004 (a presumed suicide by drowning), Soderbergh conceived something of a final monologue for Gray, composed of existing film and video documentation of Gray’s performances as well as TV interviews and home movies. The result was the posthumous “autobiographical” movie And Everything Is Going Fine (2010).

Soderbergh doesn’t remember if it was his idea to turn Gray’s Anatomy into a film or if it was suggested to him by Kathleen Russo, who at the time was Gray’s partner and later his wife. Soderbergh had become fascinated with Gray’s work when he saw a VHS copy of Demme’s Swimming to Cambodia. This was soon after his debut feature, sex, lies, and videotape (1989), was released, seemingly coming out of nowhere to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Soderbergh must have felt the connection between James Spader’s character in his film and the persona Gray constructed through his monologues, particularly their intense voyeurism and their confusion of life and art. (Later, Gray would develop a series of pieces in which he interviewed the audience, bringing him even closer to the protagonist of sex, lies, and videotape.) When he watched Swimming to Cambodia, Soderbergh told me in 2009, just as he was completing And Everything Is Going Fine, he “had the sensation . . . of, Oh, my mind works like that too . . . I identified with the struggle to filter experience so that it seems to make sense, which is an ongoing, sometimes futile, process. To watch someone describe that struggle so well, and with such humor and detail, was intoxicating. The constant spinning and digressing and organizing seemed so genuine.”

Given that Soderbergh has long been frustrated by the confines of linear narrative and the conventional arcs of character development—he recently cited this as a primary reason for calling a halt to his directing career—it’s not surprising that he was enthralled by Gray’s ability to tell a compelling story in which, to quote Jean-Luc Godard, “there is a beginning, middle, and end, but not necessarily in that order.” After that revelatory first viewing, Soderbergh read everything of Gray’s that was available, including his novel, Impossible Vacation (1992), basically a fictionalized autobiography in which a Gray-like character named Brewster North is haunted by his mother’s suicide. And then, because, he explained, he wanted to be around Gray to see how he operated as a performer, he cast him in a major role in his third feature, King of the Hill (1993). He told Gray that the character he would play was ruled by regret, so much so that he kills himself. And that cinched the deal.

Similarly prolific, Soderbergh and Gray could be two sides of the same coin in terms of their creative processes. Gray always dug in the same hole, but from slightly different angles—or to put it less metaphorically, he discovered in each succeeding piece that new experiences inevitably churned up and were filtered through the same trove of childhood memories. Gray was the opposite of a character actor, although he could be an excellent mimic for a moment or two when he wanted to evoke an encounter between himself and someone else within a first-person monologue, in which he always played “Spalding.” Soderbergh, on the other hand, is the ultimate anti-auteurist auteur, determined never to repeat himself, or anyone else.

The film versions of Swimming to Cambodia and Monster in a Box preserve the basic theatrical situation of the original performances. Gray is onstage, facing a live audience, whose responses we hear and which we occasionally see in cutaways. He delivers his monologue as he did live, his attention and gaze shifting repeatedly to take in one or another group of spectators. He never acknowledges the presence of Demme’s or Broomfield’s camera. These are essentially live concert films. Ever the contrarian, Soderbergh does away with the audience. Gray’s Anatomy takes the form not of a live performance but of a reverie that’s very close to a kind of partly absurd, partly terrifying dream that actors frequently have, in which everything they presumed they could count on when they came onstage eludes them. Basically, the film evokes a mental space; it takes place within the creative, paranoid consciousness of Spalding Gray. In this, it resembles Schizopolis (1996), the film Soderbergh had finished a short time before.

Schizopolis is as close as Soderbergh has come to putting a first-person confessional on the screen. Paradoxically, its farcical style depends on extreme artifice in performance and mise-en-scène. In addition to directing, writing, and photographing, Soderbergh also plays the central character and the alter ego his character seems to have generated while experiencing a nervous breakdown. Unlike Gray, who was never less than charming when describing doubt, terror, and compulsive bad behavior, particularly in the sexual arena, Soderbergh goes out of his way to be abrasive and just plain repellant in his self-hatred. Nevertheless, the strategy of turning the screen into a hallucinatory psychodramatic space carries over from Schizopolis to Gray’s Anatomy.

The particular organ of Spalding Gray’s anatomy at issue in this monologue is his left eye. One day, Gray discovers, much to his horror, that when he closes his right eye and looks only through his left, everything appears blurry and distorted. After procrastinating for a year, he hastens up the chain of eye specialists, who unanimously diagnose his problem as a macular pucker, a condition wherein some of the vitreous humor in the eye dissolves or leaks out, causing the macula, which is at the center of the retina and is responsible for all detail in sight, to pucker up rather than lie flat.

I know a bit about macular puckers since I have one myself, and for several years, our respective puckers were the main subject of conversation whenever Gray and I would meet on Wooster Street in downtown Manhattan, where he lived and I still do. My macular pucker has never become as severe as Gray’s was, and so for about twenty years, I have followed the recommendation of my ophthalmologist to do nothing at all about it. (Sorry to bother you with these details, but I offer them as evidence that the confessional mode is contagious, and also as to why I may have a particular interest in this monologue.) Gray, however, was told that he should have a microscopic surgical procedure that, as he details in Gray’s Anatomy, involves cutting into the eye and peeling off the pucker. The surgery has a 1 to 2 percent risk of permanent blindness. Once Gray found out what could happen to his eye if he chose this route, he decided to do everything possible to avoid it, although his psychotherapist and his then longtime girlfriend, Renée Shafransky, who cowrote and directed the stage version of Gray’s Anatomy, both advised him to have the surgery and get it over with. Instead, he embarked on a quest for alternative therapies, which took him from a Christian Science practitioner to a Native American sweat lodge to a New Jersey nutritionist and ski enthusiast to a Philippine healer known as “the Elvis Presley of psychic surgeons.” Each of these adventures led to some small revelation (and hence an opportunity for narrative digression) but no cure. It was not until he saw Richard Nixon in the office of his macular surgeon that he reluctantly opted for mainstream medicine.

Gray’s Anatomy opens with an introductory segment during which Gray is absent from the screen. The camera then drops down from an ambiguous cloud of soft white light to find Gray’s face, and continuing its move by pulling back, reveals that he is seated behind a wooden table, on which there is a glass of water, a microphone, and a notebook. The table and the three objects are the signature elements of Gray’s performances, the signs that we are in Spalding Gray country. But as Gray begins to speak, the tone of his voice urgent and confiding, we may notice that he is looking straight into the lens of the camera—in other words, he’s looking at us. Gray is describing an incident that occurred when he was leading one of his storytelling workshops. After instructing the participants to look one another straight in the eyes, he found himself locked into the large blue peepers of Azaria Thornbird, a woman, as we later learn, of significant sexual accomplishments involving her astral body; that is, sex in absentia—not unlike the experience of eye contact in absentia that we may have watching this movie.

As Gray looks at Azaria, her face seems to melt and then dissolve into burning white light. Watching Gray describe this strange perceptual experience, we notice that the spotlight on his face is becoming increasingly intense, so that it, too—Gray’s face, that is—becomes pure light, and then recomposes itself, just as Azaria’s face seemed to recompose itself when the light emanating from it somehow whooshed out the window. In the film, there is a window behind Gray, but no light whooshes out of it. Nevertheless, we have here the first demonstration of how Soderbergh will, throughout the film, illustrate and reinforce Gray’s descriptions of what he sees and feels, using the most basic filmmaking tools—lights, gels, smoke, shadow effects.

As Gray becomes frantic about finding a cure, and his quest takes him into some very outré places, Soderbergh further destabilizes the space through movement. Always seated in his chair—which can spin 360 degrees—his elbows leaning on the table in front of him, Gray is magically transported from one place to another; he’s literally dollied about, the places mostly indicated by rear projections. The hallucinatory climax of his travels takes place in the operating room of the Philippine psychic surgeon, which is depicted as a shadow play projected onto a bloodred scrim behind him. That Gray is never completely enveloped by the events he recalls, but always remains an outside observer, even when he appears to be choking on the special-effect smoke in the sweat lodge, doesn’t make his story any less compelling or terrifying. Indeed, it is the distance between Gray’s first-person narrating voice and the events he describes that makes all his work at once anxiety-provoking and hilarious, a state Soderbergh perfectly captures. And Soderbergh reinforces this distance in Gray’s Anatomy with his mise-en-scène, Cliff Martinez’s droll score, and Susan Littenberg’s deft editing, which complements Gray’s brilliant comic timing.

Soderbergh also introduces an element entirely of his own devising. Having eliminated the audience inside the theater, he adds a half dozen or so outside observers, who in most cases are literally outside—standing in driveways and yards that appear barren and just a bit ominous. They have all experienced eye injuries, and they view Gray’s adventures in alternative medicine with a certain skepticism. They are stand-ins for us, calling attention to our own observation of Spalding Gray in his telling of his own observational crisis. We may believe that we have been spared their—and Gray’s—dual role of being the observed even as they are observing. But if you watch this disc to the end of the credits, you will find that Soderbergh has saved his best twist for last. See you at the eye doctor.