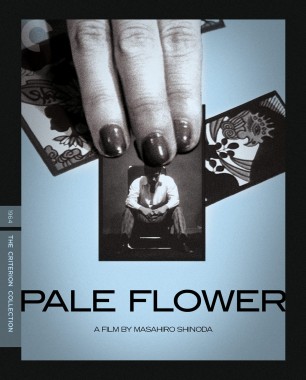

Pale Flower: Loser Take All

“There was a strong influence of Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal throughout this film,” director Masahiro Shinoda would later remember of his 1964 squid-ink noir Pale Flower, made in the days when his career as a filmmaker and founding figure of the Japanese New Wave had only recently begun and with the pellucid young Shochiku ingenue Mariko Kaga as his Saeko—his finest film’s fragile blossom. True, the fragrance of evil does cling to Pale Flower, a trendsetting bakuto-eiga (gambling film) about an aging yakuza named Muraki (Ryo Ikebe), fresh out of prison, and the giggling and mysterious siren, Saeko, who gaily escorts him to his doom. Evil, and death. “When I finished shooting it,” Shinoda continued, speaking to interviewer Joan Mellen more than a decade after the film’s release, “I realized that my youth was over.”

A sumptuous sonnet to unrequited amour fou, Pale Flower remains Shinoda’s most enduring creation. Brooding and nigh unreadable, with its morally murky fusion of modernism and mayhem—fast cars and fatal attractions, Sartrean silences and operatic apogees—the film is a perennial favorite among genre aficionados and art-house cine-sophistos alike. Is it the former who plump for assigning it official status as a Seminal Moment in the History of the Yakuza Film and the latter who luxuriate in its ultrastylish attitudes toward, and nihilistic getaways from, that gangster genre’s time-honored and often code-bound form, or vice versa? It scarcely matters: few come away from Pale Flower less than dazzled, and many of us have remained to relish its bottomless blacks and sepulchral whites time and again. A hybrid, then, this Pale Flower—but a hardy one, with vérité glimpses of Yokohama’s pedestrian exteriors and crowds of curious faces (often staring directly at the camera lens) alongside lush, gorgeously photographed expressionist atmospherics, and two extraordinarily attractive people caught in the middle, surrendering themselves, together yet always alone, to fits of maniacal laughter and long, Camusian gazes into the void.

Sylphic and unknowable, Saeko blossoms under an ebony sun: a lone, almost translucent child-woman glimpsed first in the near enveloping darkness of a gambling den at night, fertilized by sweating men, tattooed and half-disrobed, hovering and darting at the parched flutter of money. Caught in a trowel-full of tepid light from the brazen bulb strung low above the hanafuda mat, Saeko rises like a luminous frond from a crack in a mountain made of man flesh and shadows—rises . . . and incandesces. A glowering skull fixes its gaze upon her, mesmerized: the skull of the man, Muraki, who will soon introduce her to the exhilarations of sudden death. The hanafuda—domino-size hard “flower cards,” brightly adorned with seasonal images of peonies and paulownia—are shaken and shuffled until their rattle becomes the clatter of a clutch of falling sticks, the din of a dozen tap dancers, an army of castanets. Bets are placed, the cards upturned, gasps and groans exchanged among the gamblers, yet not a ripple disturbs Saeko’s milky surface. Tonight, only death is on a winning streak.

Just back from a three-year stretch for a gang-related killing, Muraki is a study in early middle-age suave; no one else (before the heyday of Bunta Sugawara, anyway) could have gotten away with wearing such a ridiculously loud plaid suit, but the buzz-cut and glisteningly butch-waxed Ikebe pulls it off with graying aplomb. He’d earned it. Ikebe had started in pictures in the mid-1940s, and found success playing a range of cops, toughs, and other stolid types throughout the 1950s, in everything from Yasujiro Ozu’s Early Summer (1951) to Ishiro Honda’s Battle in Outer Space (1959). He went on playing seasoned tough-guy roles long after Pale Flower, often supporting Koji Tsuruta or Ken Takakura in exactly the sort of Toei Studios yakuza films that Shinoda’s groundbreaker would continue to inspire into the 1970s and beyond. Ikebe (who passed away in late 2010) was forty-five the year he starred in Pale Flower; Mariko Kaga was only nineteen. Her first film had been for Shinoda less than a year before (Tears on the Lion’s Mane), and she immediately became a radiant hot spot on the Shochiku talent roster; after Pale Flower, she suddenly seemed iconic. With her slightly petulant upper lip and ultra-enigmatic Mona Lisa gaze, Kaga’s epically bored, thrill-hungry Saeko—whose motives we never learn and background we never hear about—might be André Breton’s flummoxing Nadja by way of a Go-Go Age moga (modern girl): elusiveness incarnate. By the end of 1964, Kaga had starred in a kind of celebrity vehicle carefully calculated to exploit every facet of her alternately buoyant, frail, erotic, giggling, and haunted persona: Crazed Fruit director Ko Nakahira’s Yuka on Monday, the story of a Catholic waif/teenage call girl who gives her all to her every customer . . . with the exception of her kiss. A dreamy dish of lingerie fantasies for Kaga fanatics, Yuka on Monday proved an otherwise dreary grab at already clichéd sub-Godard-isms. A year later, her turn in Nagisa Oshima’s Pleasures of the Flesh would also be a bit of a disappointment, her far too heavily made-up muse appearing in far too little of the film. Yet under Shinoda’s guidance—in Pale Flower as in With Beauty and Sadness (1965), the director’s next film, a delicately pastel-toned adaptation of a Yasunari Kawabata novel—Kaga grew to become one of the most compelling actresses of her age, and has enjoyed a long career, mainly in television dramas.

Only thirty-three and a few years into his directorial career as he made Pale Flower, Shinoda had begun as an assistant director at Shochiku in 1953, the year before Oshima came aboard. A dutiful employee, Shinoda wouldn’t make the leap to director until his younger colleague, by then known as a vociferous film critic and studio malcontent, made his debut, 1959’s A Town of Love and Hope, which proved both a critical success and the first ripple in what would soon become the studio’s in-house nouvelle vague. Shinoda’s own first feature was a rock-and-roll rise-and-fall story written quickly to capitalize on Neil Sedaka’s international hit “One Way Ticket.” It failed at the box office, and while Shinoda made half a dozen other films over the next couple of years—including, among more run-of-the-mill studio melodramas, the politically fraught, Shuji Terayama–scripted Dry Lake, the story of a hapless revolutionary wannabe, set in the midst of the anti-security-treaty demonstrations of 1960, and the eccentric live-action comic book Killers on Parade (a.k.a. Murders 8, a.k.a. My Face Red in the Sunset), which in several ways beat Seijun Suzuki to the punch, with its cartoonishly color-coded hit men, absurdist sense of mayhem, and occasional bleatings of a hit woman’s pet goat punctuating the pratfalls—it wasn’t until 1962’s Tears on the Lion’s Mane that he seemed finally to secure his footing. Tears was a bitter end-of-innocence story set on the Yokohama dockside, its deeply moody, black-and-white nightworld imbued with a remarkably bleak attitude toward the rock-and-roll westernization of the Japanese spirit. Floating corpses punctuate the proceedings, a poster for L’avventura is glimpsed on a café wall, and the film’s emotional climax comes during a kind of R&B scat song of annihilation sung sotto voce—shuddered and moaned, more like—by the film’s doomed young hero, driven to his wit’s end by a cruel twist of fate. Eventually, the cops arrive to drag the crooning killer away, but the point has long since been made: roll over, Ozu, tell Mizoguchi the news.

With Pale Flower, Shinoda came decisively into his own—but he didn’t do it alone: shot by Masao Kosugi (who photographed over a dozen of the director’s finest films); based on an original story by the leading figure of the taiyo-zoku (sun tribe) generation and Crazed Fruit scenarist Shintaro Ishihara; scripted by Shohei Imamura’s future Vengeance Is Mine screenwriter, Ataru Baba; anchored by the delicate balance between the cool and the terse supplied by stars Ikebe and Kaga; and scored by Shinoda’s recurrent collaborator the avant-garde classical composer Toru Takemitsu, here working at the peak of his talents to create a sonic scroll painting of banshee horns, amplified Doppler-effect string glissandi, and rattlesnake rhythm shaking, the production proved a perfect storm of talent, with Shinoda confidently at the helm. Yet while roundly acclaimed a masterpiece in retrospect, Pale Flower didn’t originally turn out quite to the pleasure of all involved. Baba especially was incensed at the ways he felt Shinoda’s dazzling technique and dizzying cutting obscured the script he had labored over and overemphasized its implicit nihilism. Shochiku, in fact, decided to shelve the film for a number of months, not releasing it until the following year, though that probably had less to do with Baba’s dented scribe pride than with the film’s copious scenes of high-stakes gambling, which legal authorities apparently felt were excessive and a bit too intimately detailed. Indeed, the visual rhythms of the game of “matched draws” called tehonbiki, played here—if not the rules of the game itself, which will elude all but the most specialized audiences—are a central component of the film’s mesmeric effect. Arranged to Takemitsu’s hyperpercussive mini symphonies, these scenes draw the viewer ever deeper into the vortex of the game’s mysteries—just as they do the death-driven Saeko and Muraki, who finally surrender themselves to greater wins, and greater losses, when the thrills of the game are no longer enough.

“I would like to be able to take hold of the past and make it stand still, so that I can examine it from different angles,” Shinoda once revealingly remarked, in the context of one of his most celebrated films, 1969’s Double Suicide. A graphically dazzling rethink of playwright Chikamatsu’s classic tale of tragic lovers bound together by their rejection of traditional customs that reinvents centuries of Japanese illustration and design under the utterly modern imperatives of pop art, Double Suicide embodies Shinoda’s near cubist attitude toward the past in its most rigorously perfected state. Yet Pale Flower—with its doomed crypto-lovers who substitute high-stakes gambling for carnal communion and revel in each other’s excesses to the exclusion of anything but almost certain oblivion—is clearly one of Double Suicide’s prismatic historical precursors, and nowhere is that more evident than in the moment when Shinoda at last finds Muraki and Saeko in a futon together (they’ve scrambled beneath the covers to hide from police during a raid, and once again are substituting hanafuda for hanky-panky) and positions his camera directly over the bed, precisely prefiguring the latter film’s disorienting signature image. Elsewhere in Pale Flower, the director manages to suggest the fragmentation of time and the fusion of past and present in an assortment of disparate ways: a haunted clock shop inhabited by both Muraki’s preincarceration lover and a thousand ticktocking reminders of the time that has already passed him by; Muraki’s black-fur-carpeted bachelor pad, where paint peels from a dingy wall in an enormous, angst-imbued echo of a traditional enso ink painting—the single-brushstroke circle that functions as Japan’s Zen rendition of an action painting. An age-old (attempted) act of fraternal retribution unfolds in a thoroughly modern bowling alley where an elevator-music version of “It’s Now or Never” spills like maple-syrup rain over the proceedings. (Akira Kurosawa would use the same tune to underscore the deformations of Japan’s postwar generation in High and Low that very year.) Even the film’s climactic episode of thrill-kill violence manages to merge present and past: as Muraki stabs a rival gang boss to death in a public restaurant while Saeko observes with petrified awe, Shinoda’s imagery specifically evokes the horrific and graphically photographed onstage assassination of left-wing political leader Inejiro Asanuma in 1960, even as the baroque operatics of the soundtrack cut the moorings of the contemporary in search of some timeless state of orgasmic, annihilating grace.

Forever conflating visions of liberation and confinement, Pale Flower (whose Japanese title, Kawaita hana, translates more literally as “dry” or “withered” flower, clearly indicating that death, more than simple pallor, is what’s most crucially at stake) begins with an image of freedom—sculptor Fumio Asakura’s Degas-like depiction of a lithe young woman with arms spread wide to the sky, Tsubasa-no-zo (Statue of Wings), a long-familiar landmark at Tokyo’s Ueno Station—and closes with the enormous, tomblike doors of a prison yard clanging shut. The infernal banging of heavy industry, unseen but overheard from sources somewhere far offscreen, recurrently fills the air, and hearses seem forever on patrol in the city’s streets. A mysterious junkie hit man prowls the shadows, flinging scalpels at Muraki as he navigates the night, searching for a single burning flame in the urban purgatory the aging gangster has already long since recognized as overrun with half-living citizens, their daily commute a zombie march, their new Japan a Land of the Rising Dead. And for a moment, Saeko provides that spark: a soft and quavering incandescence that all too briefly illuminates the path by which they both might journey toward sunrise—a pale and bewitching fire-flower, a faint and inexorably dithering flame.