Cronos: Beautiful Dark Things

Guillermo del Toro understands the power of fairy tales. Not the prettified romances of Charles Perrault, who tamed the Brothers Grimm for French drawing rooms, or the charming animal fables of Aesop, or the reassuring moral lessons Disney made of “Cinderella” and “Sleeping Beauty,” but brutal tales of cruel fate, painful choices, and irreversible consequences, stories whose roots lie deep in the dark woods of our collective unconscious. Good may prevail, but there will be blood.

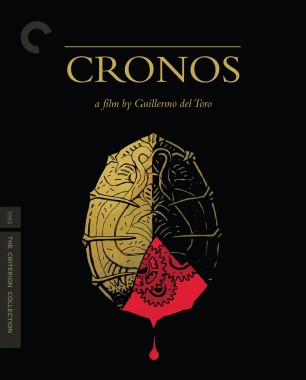

A melancholy modern-day spin on classic horror themes, Cronos (1993) was the then twenty-eight-year-old Mexican writer-director’s feature film debut, and it marked the arrival of a startlingly distinctive voice. Cronos was fresh without being trendy, exquisitely designed without losing sight of the fact that even the coolest creature—and the film’s cronos device, an intricately carved mechanical bug with a living core, is extraordinarily cool—can’t compensate for thinly conceived characters or a tediously formulaic narrative. It swept the 1993 Ariel awards—Mexico’s Oscars—winning in nine categories, including best picture, director, and original screenplay. A month later, it received the prestigious International Critics’ Award at Cannes, and subsequently won over festival audiences from Portugal to Russia.

That Cronos failed to generate equal enthusiasm in the United States was disheartening but no great surprise. Horror and exploitation movies can be a good way to break into Hollywood: their built-in fan base is famously forgiving of such rookie scourges as subpar/uneven acting and poor production values, so they stand a good chance of making some money, and movies that make money open industry doors. But they’re a notoriously bad way to launch a career in serious filmmaking (the illustrious Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, and Oliver Stone notwithstanding). Cronos had two strikes against it: it was a vampire movie, and it was (mostly) in Spanish. By the early 1990s, America’s always modest but ever faithful art-film audience was aging out of existence, and for American distributors, foreign-language films were always art—people had to read in the theater, for heaven’s sake. At the same time, the theatrical exploitation market was dying: drive-ins were gone; urban renewal projects were shuttering the low-rent inner-city theaters that had once shown double and triple bills and introduced Americans to filmmakers as diverse as Stone, Dario Argento, Georges Franju, Mario Bava, Jean Rollin, and Peter Weir; and the sheer volume of direct-to-video releases virtually guaranteed that good movies would get buried by bad. The wonder is that a handful of high-profile, mainstream critics (including the New York Times’s Janet Maslin, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, and the Los Angeles Times’s Kenneth Turan) stumbled across Cronos and duly noted that it was no hack job, pun invariably intended.

But del Toro hadn’t made a horror movie thinking it could be a stepping stone to bigger and better things. He made Cronos because he wanted to, and kept making genre pictures long after he could have stopped. Del Toro has admitted ruefully that he kills himself doing the kind of films other people knock out for quick cash, and his devotion shows: Cronos and The Devil’s Backbone (2001) are as subtle and rich as any highbrow coming-of-age drama, and who knows what Mimic (1997) might have been had the production not been so legendarily troubled—its early scenes are magnificently eerie. Unlike many U.S. genre filmmakers of his generation, del Toro doesn’t love schlock—tacky rubber monster suits hold no sway over his imagination. He loves freaks and beasts because they’re outcasts, the flawed, damaged reflections of human nature. If there’s any filmmaker with whom he should be compared, it’s David Cronenberg, who eventually earned his ticket out of horror and uses it only when it suits him.

Born and raised in Guadalajara, del Toro was a bookish and imaginative boy, both prone to nightmares and in love with the macabre. When his father, a successful Chrysler dealer, came into some money, he invested in two sets of encyclopedias, one on art and the other on medicine, both of which his son devoured. Del Toro loved comic book art and fine art with equal passion; in his mental gallery, works by Richard Corben and Bernie Wrightson hung next to Rembrandts and Caravaggios. He drew extremely well, and like many future filmmakers, appropriated his father’s 8 mm camera as a youngster, returning it only after he had graduated to 16 mm. And then there was del Toro’s Catholic grandmother, who cast a long, dark, but richly resonant shadow over his formative years. To call her devout would be an understatement; del Toro has compared her to “Piper Laurie in Carrie.” She was less than enchanted with her grandson’s macabre warp of mind . . . so not enchanted that she exorcised him herself—twice—and lamented until her death his inability to create beautiful things. Del Toro, of course, was creating beautiful things, if not necessarily pretty or conventionally pious ones. His eye was attuned to the beauty in the darkness.

It was Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) that put del Toro on the mainstream map. Critics waxed rhapsodic, the notoriously conservative members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences nominated it for six Oscars, and moviegoers who would never have considered seeing Blade II (2002) or Hellboy (2004) surrendered to its dark charms. But everything that made Pan’s Labyrinth so much more than a run-of-the-mill spook tale was already evident in Cronos: the dark depiction of childhood, the deep understanding of mythic imagery, and the rich, complex relationships that drive everything the characters do, for better or—all too often—for worse.

Cronos was the culmination of del Toro’s youthful experiments making short monster movies, which grew progressively more elaborate and sophisticated. They forced him to learn how to create special effects, from simple squibs to gaping wounds and fetus creatures, because there was no one in Guadalajara to do them for him. Del Toro took those skills and opened his own effects shop as a way of bankrolling Cronos. In the decade before the project finally went in front of the cameras, he also gained invaluable experience and professional connections, including working on a Twilight Zone–like TV show called Hora marcada with Alfonso Cuarón and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (who would go on to collaborate on Y tu mamá también and Children of Men). Del Toro and Cuarón are now partners in Cha Cha Cha Productions, along with Alejandro González Iñárritu, whom del Toro met after cold-calling him to say that he’d seen an early cut of Amores perros and it needed trimming.

Cronos is a young man’s movie (though del Toro fretted that he was a late starter), but its emotional sophistication is striking. At the film’s heart is the relationship between a reluctant vampire—aging antiques dealer Jesús Gris, played by veteran Argentine actor Federico Luppi—and Aurora (Tamara Shanath, who has made only a handful of subsequent films), the silent, watchful granddaughter who adores him. Infected with eternal life by an ancient insect hidden within an intricate clockwork one, Gris is gradually transformed into a pallid creature who must shun the daylight and drink blood to survive. He is hunted by a ruthless thug (Ron Perlman, best known then for the cultish romantic fantasy television series Beauty and the Beast, and later for del Toro’s Hellboy) whose wealthy but infirm uncle covets the cronos device, and he is degraded (dressed in dapper black tie for a New Year’s Eve ball, he can’t resist lapping blood from the men’s room floor), brutalized, and eventually killed . . . except, of course, that he can’t die, and escapes his own cremation to creep home in the pouring rain. If your heart isn’t broken by the scene in which Aurora opens the door and hands her grandpa a fluffy towel, then puts him to bed in a coffinlike toy box with stuffed animals and a plastic dolly for company, your heart is unbreakable.

Del Toro has said that were he to make Cronos now, it would be a very different film. And though that’s no doubt true, it’s hard to imagine its being a better one. In the words of the doomed alchemist who creates the gold bug and learns that immortality comes at a price: suo tempore. Everything in its time.