Clashing Values and Wild Facts

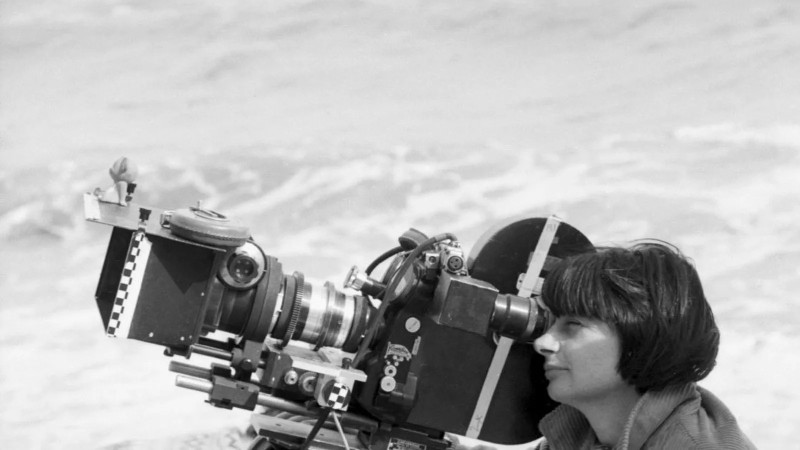

Three weeks before Shahrbanoo Sadat (Wolf and Sheep, The Orphanage) began shooting No Good Men, which opened this year’s Berlinale on Thursday, her lead actress backed out. Sadat herself then stepped in to play Naru, the only camerawoman working for Kabul News. Battling with her cheating husband over custody of their young son, Naru falls for the station’s top journalist, Qodrat (Anwar Hashimi), just as the U.S. is about to pull out of Afghanistan, leaving the Taliban to take over the country.

- Starting today, Film at Lincoln Center pays tribute to Diane Keaton, who passed away last October, with a weeklong series, Looking for Ms. Keaton. At 4Columns, Erika Balsom revisits Richard Brooks’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977), starring Keaton as a teacher exploring her sexuality. “Misogynist violence is ubiquitous, and the freer a woman is, the more likely she is to provoke it,” writes Balsom. “By representing this in such lurid detail, with Keaton’s beguiling naturalism and eccentric vulnerability attracting the viewer’s admiration and identification like a magnet, Goodbar becomes something other than a mere tale of chastisement: it offers an account of clashing value systems in a moment of societal transformation.”

- This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of the release of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. NPR has put together a forty-minute collection of excerpts from archival interviews with Scorsese, Jodie Foster, Harvey Keitel, Cybill Shepherd, Albert Brooks, and Paul Schrader, who wrote the screenplay, while Esquire’s Anthony Breznican surveys the initial critical response, sampling a rave from Pauline Kael, a pan from Rex Reed, and a split verdict from Vincent Canby of the New York Times. The Guardian’s David Smith has a good long chat with Schrader, who recalls Robert De Niro floating the idea of a sequel: “I said, ‘Bob, first of all he’s dead, but if he wasn’t dead, he’s not riding a taxi any more. He’s sitting up in his cabin in Montana setting off bombs and his name is Ted Kaczynski.’”

- For the Baffler, Robert Rubsam writes about three of last year’s standout films, Mona Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee, Caroline Golum’s Revelations of Divine Love, and Oliver Laxe’s Sirât: “Spiritual cinema is fundamentally an aspiration: it must reach out toward something it cannot ultimately depict. Yet it reaches all the same. Practitioners of the art pursue what William James called ‘wild facts,’ that mixture of the impossible and the unassimilable which crops up in any study of the affective dimensions of human culture . . . In his book They Flew, the historian Carlos Eire attempted to parse what such impossible absurdities meant to the people who believed in them—and what it might mean for those on the other side of modernity, with its redefinition of the line between the rational and the irrational, to allow themselves at least the potential for belief.”

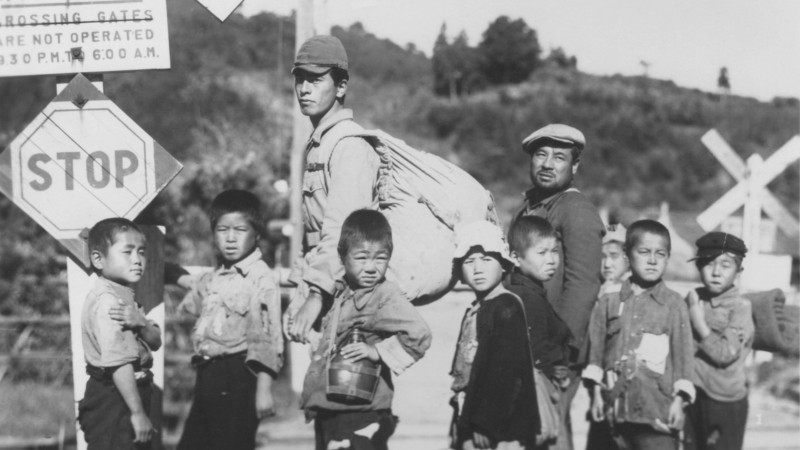

- Before the Trump administration sent him back to California last month, Gregory Bovino led Operation Metro Surge, the crackdown on illegal immigration in Minneapolis. Bovino has said that he was inspired to become a U.S. Border Patrol officer by Tony Richardson’s The Border (1982), starring Jack Nicholson. “If that’s the case,” writes Alexander Nazaryan for the New Yorker, “it’s a little like entering the hospitality industry after watching The Shining.” The Border is “about the moral compromise and human costs that come with immigration enforcement. But it is also a commentary on the mythic plenitude of American life; the film prods you into wondering whether that allure is illusory.”

- Six weeks after the death of Brigitte Bardot, Jeremy Harding looks back in the London Review of Books on her performances—dwelling in particular on Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963)—and gathers commentary on B.B. from Roland Barthes, Marguerite Duras, and several other French luminaries. Harding revisits the period when the paparazzi “had her under de facto house arrest” as well as the post-retirement hard swerve to the political right. “Her racism was a focused form of misanthropy, the corollary of her affection for animals,” writes Harding. “It was easy to poke fun at Bardot by the end but hard to figure out whether older attitudes towards her—jealousy, envy, misogynistic lust—might not be enjoying a new lease of life in different guises, including political indignation. Was Bardot really an incarnation of ‘La France,’ as [far-right political leader Marine] Le Pen claimed?”