The Past Is an Intruder

The Sight and Sound poll of more than a hundred critics from around the world caps a week of best-of-2025 lists and awards. There are surprises here, but not in the top spot: One Battle After Another, Paul Thomas Anderson’s “not-really-Pynchon, not-quite-action-movie,” writes Michael Koresky in the forthcoming issue, “which stormed the hearts and minds of twenty-first-century movie diehards who are sick and tired of the cinema of failure but cannot let go of the American ’70s, a time of auteurist mythology defined by both the artistry of Altman and sell-out spectacle of Star Wars (1977). The admiring critical response has been justified but also conspicuous: here, finally, is something that dares to be satisfying while refusing to paint a rosy picture of where we’re at.”

- “You know that feeling you get when you’ve just gotten back from the dry cleaners a pair of slacks, Dacron slacks, and you reach your hand in a pocket and you feel those fuzzy sandwiches with your fingers?” David Lynch once asked novelist Barry Gifford (Wild at Heart). “Well, that’s the feeling I’m looking for.” The two were discussing the screenplay they were writing, Lost Highway (1997), which—as Gifford wrote in a 2002 piece now running in the current issue of Artforum—is “set in a place, a city, a landscape, that is neither here nor there, a timeless form, presented within a nonlinear structure—a Möbius strip, curling back and under, running parallel to itself before again becoming connected, only there’s a kind of coda—but that’s how it goes with psychogenic fugues. Figure it out for yourself, you’ll feel better later; and if you don’t figure it out, you’ll feel even better, trust us.”

- In the New York Review of Books, Geoffrey O’Brien looks back on this past summer’s Locarno retrospective, Great Expectations: British Postwar Cinema, 1945–1960, curated by Ehsan Khoshbakht, who has also edited the accompanying book. “Such a retrospective functions as an artwork in itself, creating polyphonic effects as the films seem to watch and comment on one another,” writes O’Brien. “Actors major and minor—Dirk Bogarde, Hermione Baddeley, Kathleen Harrison, Trevor Howard, Margaret Rutherford, Ian Carmichael—became familiar presences as they popped up in multiple and distinct roles, suggesting a familial network. Daily immersion established a ghostly identification with the audiences for whom the films were originally intended.” For those who stuck with the forty-five-film program, “it did not take long to feel that one was living for the time being in postwar Britain, that is to say in the aftermath of a catastrophe and with little assurance of where it all was going or of what might already have been lost forever.”

- In the Guardian, Terry Gilliam and John Boorman remember Tom Stoppard,Amelia Tait writes about fake movies within real movies (Angels with Filthy Souls in Home Alone, for example), and Andrew Pulver talks with Kevin Brownlow about the two films he made with fellow film historian and director Andrew Mollo, It Happened Here (1964) and Winstanley (1975). Both were “essentially self-produced, tiny-budget affairs, but amazingly consequential in their impact, then and now,” writes Pulver. “From our vantage point they look bizarrely prescient—which is why filmmaker and curator Stanley Schtinter is hosting a rare cinema screening of both films at the Close-Up Film Centre in London tomorrow.” It Happened Here “posits an England occupied by the Nazis, its inhabitants caught between bending the knee to the invaders and standing up to them,” while Winstanley is “perhaps the closest British cinema ever got to Pasolini.”

- With each new issue of Cineaste, the magazine posts a solid set of online exclusives. In the latest, we have David Sterritt on Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) and Adam Bingham on Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963), two festival reports, and interviews with two filmmakers grappling with the pandemic and its aftermath. R. T. Thorne was working on 40 Acres when COVID hit “and we started to realize that the infrastructure our societies are built on is extremely fragile.” Olivier Assayas, whose autobiographical Suspended Time was shot in his countryside home, hoped “that we were going to wipe the slate clean. That we were going to start everything anew. That we had the right to say that my generation had failed, that we’d missed a turn in the road, and that we now had the chance to get back on the right path. And that perhaps there was the possibility of making something good out of something evil. It’s not what happened.”

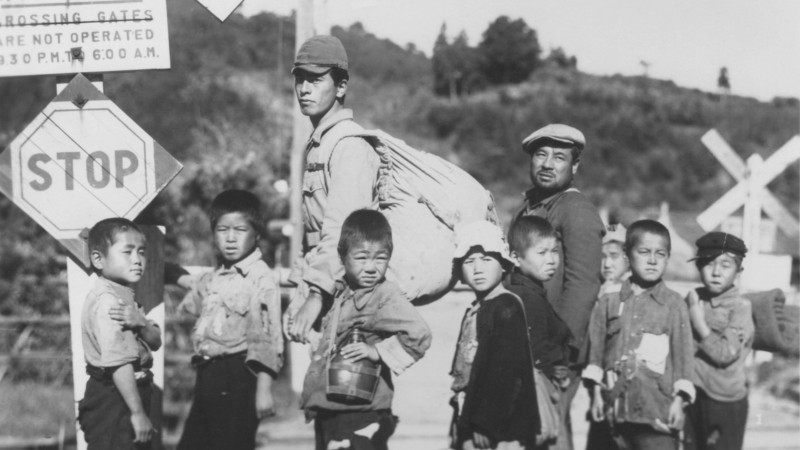

- The latest issue of Found Footage Magazine is the first to be freely accessible online. Along with reviews and essays, there are several interviews, including Sibley Labandeira’s with Rick Prelinger, the founder of the Prelinger Archives, and as Labandeira emphasizes, “so much more than a custodian of moving images and sounds: he is also a filmmaker, writer, educator, curator, open-access advocate, and above all a keen observer of the present.” For Prelinger, “defamiliarization” is “probably one of my guiding principles . . . When you take a piece of the past and you put it into the present, it’s an intruder. It may be a benevolent intruder, but it is an intruder, it’s an interruption of this amnesic race towards the future.” Defamiliarization is “a really, really important process and I want to encourage it.”