Visualizing Dread

“The last thing that Björn ever wanted, I am certain, was to be in movies,” wrote Dirk Bogarde of his fifteen-year-old costar in Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice (1971). Björn Andrésen, who passed away this past weekend at the age of seventy, had been pressed to audition by his grandmother and landed the role of the obscure object of an aging composer’s desire. He quickly grew to resent the leering attention of his director, the media, and his fans.

- The twentieth edition of Reverse Shot’s annual Halloween Special A Few Great Pumpkins offers Michael Koresky on Mervyn LeRoy’s “dark, silly, but also genuinely nasty” The Bad Seed (1956), Greg Cwik on Tommy Lee Wallace’s “bold and bizarre” Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982), Jeff Reichert on Robert Zemeckis’s “Hitchcock-humping hoot” What Lies Beneath (2000), and Chloe Lizotte on John Smith’s The Black Tower (1987): “The horror can come from anywhere.” Christine (1983) boasts John Carpenter’s “signature stylistic touches in every scene,” writes Justin Stewart, and with Cure (1997), Beatrice Loayza finds Kiyoshi Kurosawa demonstrating “the ease, the mere work of calibration, with which seemingly normal people are liable to crack and spill forth their ugliest bits.”

- On a recent episode of Cannonball, host Wesley Morris spoke with Eric Hynes about scary movies, both agreeing that neither sought out jump scares or gore but rather that low-simmering yet often unbearably intense emotion, dread. They talk about a lot of great movies: Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day (2001), and so on. But not Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (1957), starring Dana Andrews as psychiatrist Dr. John Holden, “a sardonic skeptic of mystical powers and things that go bump in the night,” as R. Emmet Sweeney describes him. “Unfortunately for him, Tourneur is a master of visualizing dread, at uncanny images that disturb the orderly corridors of consciousness.”

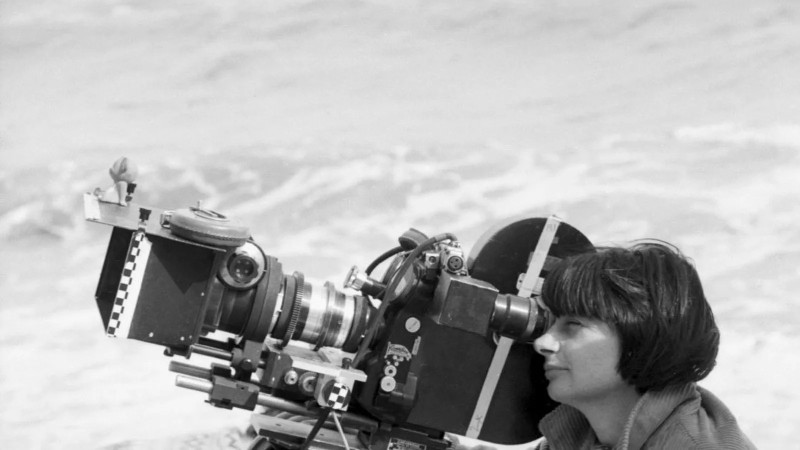

- “I’ve been researching and writing about nuclear war—its history, politics, science, and strategy—for more than forty years,” writes Fred Kaplan for Slate. “None of the many books and films that I’ve consumed on the subject have filled me with such overpowering dread as Kathryn Bigelow’s new movie, A House of Dynamite.” Talking to David Canfield in the Hollywood Reporter, Bigelow—recently profiled by Manohla Dargis in the New York Times—and screenwriter Noah Oppenheim have come to the defense of their depiction of a nuclear emergency following criticism from the Pentagon. As a film, A House of Dynamite has split critics pretty much down the middle. But philosopher and critic Steven Shaviro argues that “the combination of intimacy and affective intensity with an otherwise anti-subjective formalism is precisely what sets Kathryn Bigelow’s films apart from nearly everything else in the entire history of the movies.”

- Radu Jude’s Dracula has sparked a bloodbath of exasperated reviews—4Columns managing editor Ania Szremski calls it a “nearly three-hour exhausting provocation”—and a Notebook roundtable discussion in which editors Chloe Lizotte and Maxwell Paparella tackle this “multi-part riot of horror, comedy, history, politics, sex, and death” with critics Edo Choi, Elissa Suh, and Keva York. Talking to Mark Iosifescu at Screen Slate, Jude mentions that one of the “other stories I wanted to tell in the film was about a guy who worked in the hotel industry in Ceaușescu’s times” and then became a millionaire after the Romanian revolution of 1989. One of the most trenchant critics of television coverage of the revolution was Serge Daney, and Laurent Kretzschmar has translated four texts he wrote in the immediate aftermath.

- Throughout much of his youth, critic and novelist Leo Robson was an avid moviegoer. “My taste, or at least my appetite, was indiscriminate,” he writes in the London Review of Books. “As Pauline Kael wrote in 1969, ‘when you’re young the odds are very good that you’ll find something to enjoy in almost any movie.’ [Philosopher Stanley] Cavell, whose own ‘odd education’ took place in part at the Berkeley cinemas where Kael worked as a programmer, put it in more positive terms: ‘To be drowning in the material is really the only way—not to care too much what you’re seeing, to care a lot about what you think about what you’re seeing.’” Lately, Robson has been having a tougher time warming up to even critically acclaimed new releases. “But even at my grouchiest I try to agree with Kael that praising and complaining ‘in the same breath is part of our feeling that movies belong to us.’”