The Hunt for Movies

Showcasing top award-winners from Cannes and Venice and critical favorites from Sundance and Berlin as well as promising discoveries—Filmmaker has a terrific set of twenty recommendations—the New York Film Festival opens this evening with Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt.Julia Roberts stars as Alma, a Yale professor whose protégée (Ayo Edebiri) accuses one of Alma’s colleagues and closest friends (Andrew Garfield) of sexual assault.

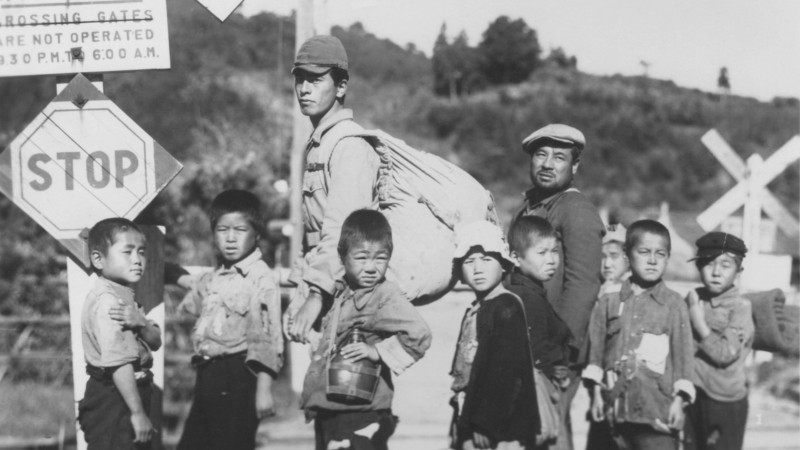

- “The hunt for movies that are missing, believed lost, or absent without leave is one of the more demanding thrills of the restorer’s mission,” writes Anthony Lane in the New Yorker. “So, what awaits the urgent patient—the movie that is plucked from imminent death? If possible, intensive care. In Bologna, this means a spell at L’Immagine Ritrovata, the laboratory that adjoins the Cineteca. To take a tour of the place, as I did in late May, is to be met by a confounding breadth of activities.” Lane takes us along, looming over workbenches, chatting with restorationist Ross Lipman, and offering commentary on several films that screened during the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in June. “To master the mysteries of film restoration, I guess, would consume your life.”

- Gian Luca Farinelli, the director of the Cineteca and codirector of Il Cinema Ritrovato, tells Lane that he’s noticed that audiences are skewing younger. Especially after the pandemic, he’s sensed “a renewed interest in film, actual celluloid film.” Talking with programmers and organizers at several Chicago repertory hubs as the Music Box Theatre and the Gene Siskel Film Center, Newcity’s Ray Pride hears pretty much the same thing. “And it’s not just that they’re showing up,” says Facets’ Emma Greenleaf, “it’s that they’re returning, bringing friends, and becoming part of a larger culture of discovery.” Jake Isgar of the Alamo Drafthouse finds that the surge “feels a lot like a byproduct of Gen Z and Gen Alpha Letterboxd-centric film culture of the aughts and the last ten years.”

- Following its 2018 release of Czech composer Zdeněk Liška’s soundtrack for Marketa Lazarová (1967), Animal Music has just put out another volume of Liška’s music for films by František Vláčil. Scoring eight features a year from the late 1950s through the late 1970s, Liška worked with Jindřich Polák (Ikarie XB-1, 1963) Ján Kadár (The Shop on Main Street, the winner of the 1965 Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film), Juraj Herz (The Cremator, 1969), and Věra Chytilová (Fruit of Paradise, 1970). In the Guardian, Miloš Hroch gathers appreciations for this innovative but overlooked composer who also “scored ten of surrealist director Jan Švankmajer’s short films. ‘He didn’t attempt to go with the mood of the film,’ the director once said. ‘He was able to discover rhythms that even directors weren’t aware of.’”

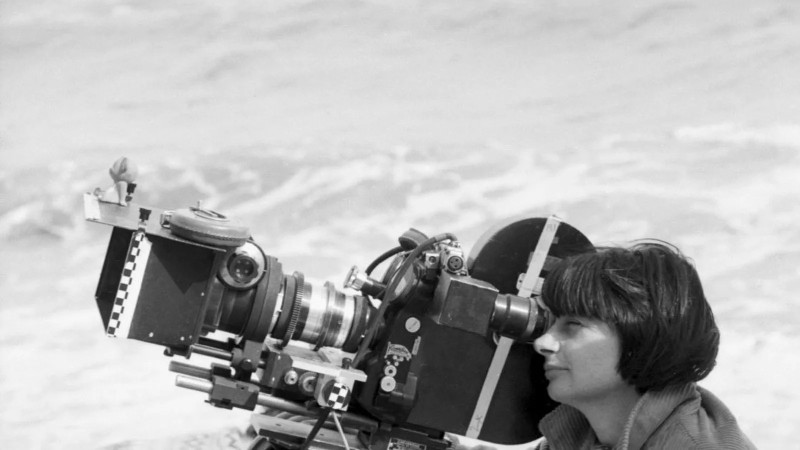

- A series of films by Ulrike Ottinger is on at the Academy Museum through October 4, and another one opens at Metrograph in New York next Friday. Several feature close collaborator, artist, and star Tabea Blumenschein, whose “striking appearance and bold aesthetic vision, especially as a costume designer, centrally informed her film characters, who often became costumed concepts: walking metaphors in living color,” writes Elissa Suh in Metrograph Journal. Blumenschein “turned her radical project of self-styling into a lifelong experiment in queer defiance. If her legacy endures unevenly in English-language film history, it is not because her contributions were small, but because they were interdisciplinary, queer—and fiercely Berlin.” The Journal is also running filmmakers Natalie Musteata and Alexandre Singh’s interview with Zar Amir, the writer and director best known for starring in Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider (2022).

- On his way into a review of Alexandre O. Philippe’s Chain Reactions—in which Stephen King, Patton Oswalt, Takashi Miike, Karyn Kusama, and critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas discuss Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)—A.V. Club film editor Jacob Oller takes a moment to issue a cri de coeur in the wake of the recent firings of several film critics at various prominent publications. “As many in my field have already written,” notes Oller, “it’s not for the normal reasons people lose their jobs. Film reviews from people who know what they’re doing haven’t gotten worse, nor has the appetite for them among moviegoers declined. Rather, studios have figured out that they can simply pay influencers for signal boosts to drown out voices that aren’t bought and paid for, while publications have determined that it’s actually a lot easier to sell ads to media monopolies when you’re not employing someone whose job often involves cutting through their bullshit.”