The Adventures of Baron Munchausen: A Reason to Believe

Fantasy requires a modicum of faith, as Baron Munchausen himself might say. And a truly enchanting film fantasy inspires the conviction necessary for that faith by way of a healthy dose of tactility. Those of us who grew up in the age of predigital effects do not simply recall with affection the great movie wonders of our childhoods; we can practically feel them: the scratchiness of the Scarecrow’s thatched body in The Wizard of Oz, the appealing nap of Mary Poppins’s flowered carpetbag, the beautifully wizened, rubbery furrows around E.T.’s soulful eyes. The allure of a perfectly preposterous fantasy world exists in the slender space between what might be and what never could. If you feel like you can reach out and touch something impossible, then maybe, just maybe, you can give yourself over to a universe unfettered by dastardly logic and suffocating reason. In other words, you must believe it, not because you want it to be real but because, well, it kind of is.

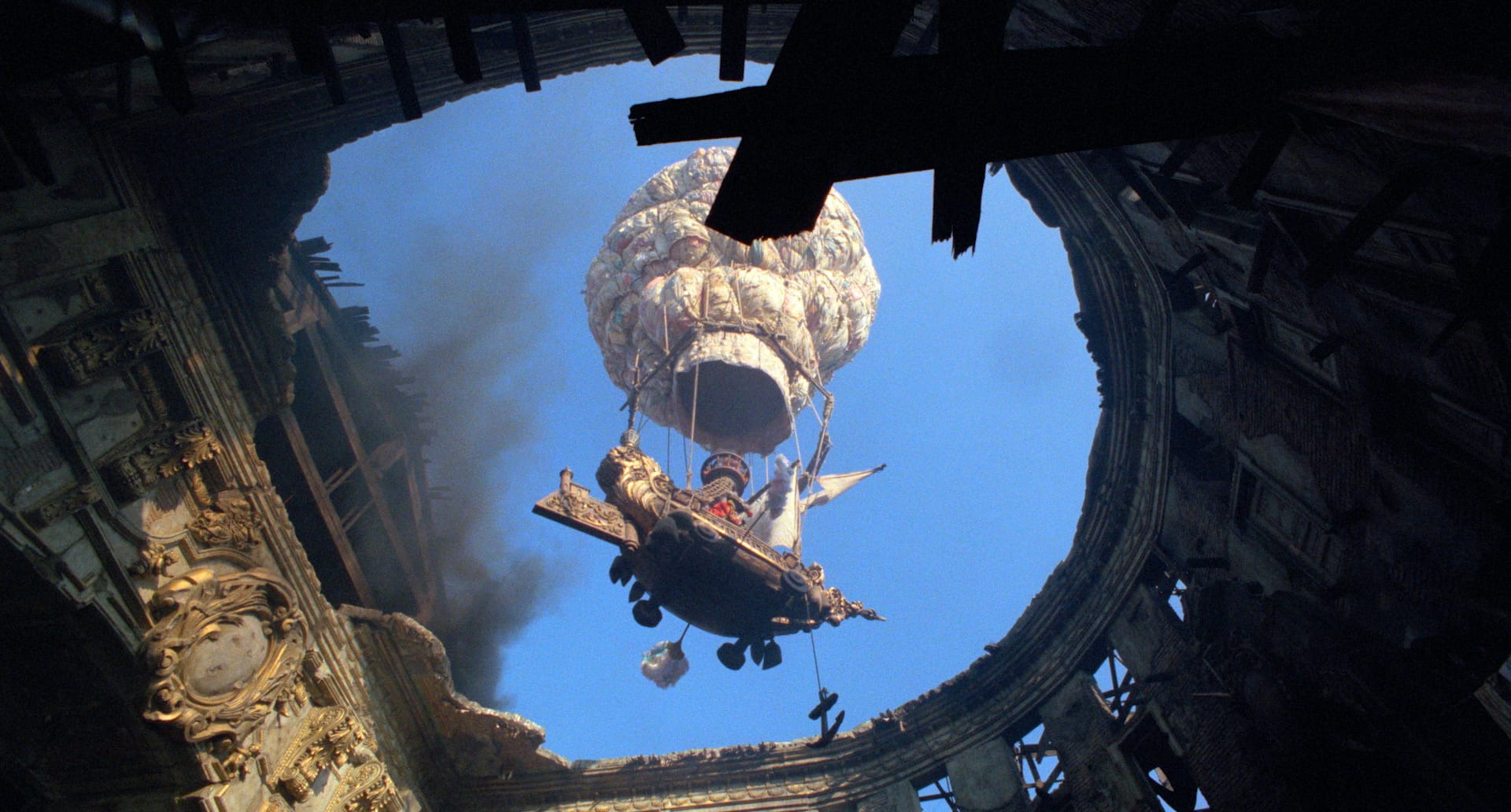

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) is a curio cabinet brimming with just these kinds of tangible impossibilities. Terry Gilliam’s film takes place during the Age of Reason, an opening title announces, though there seems to be neither reason nor rhyme to the violent conflict into which we’re dropped. The denizens of an unnamed walled European city are fending off a military invasion by the Ottoman Turks. At the same time, a local theater troupe is in the middle of a play about the legendary adventurer Baron Munchausen, and the show must go on. It’s at that performance that our hero first appears, heckling the players for mischaracterizing his far-fetched exploits, which include floating to the moon in a handcrafted balloon and narrowly escaping death after being swallowed by a sea monster. “You’ve got it quite wrong!” the aged, Pinocchio-nosed Baron (John Neville) insists loudly as he climbs onstage, while the booms of battle occasionally rock the already half-destroyed auditorium’s crumbling walls. Naturally, audience and actors alike are dubious about the trustworthiness of this man, who is decrying the fact that the play has dared to fictionalize his real fantasies.

Like Edmund Gwenn’s more avuncular Kris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street, the cranky and caustic Baron is insistent about his own improbable identity. In this case, however, the man isn’t complete myth. Baron Karl Friedrich Hieronymus von Münchhausen was a member of the German nobility born in 1720 and, by all accounts, an inveterate raconteur. Having enlisted in the Russian army to fight the Turks, he developed an arsenal of wild yarns, many considered fanciful at best. In 1785, Münchhausen was immortalized as a literary figure when Rudolf Erich Raspe—an author, librarian, and alleged former drinking buddy of Münchhausen’s—published Baron Munchausen’s Narrative of His Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, which has since appeared in many versions, under many titles. An episodic work of irreverent fancy composed in a tone of wry politesse, Raspe’s book combines military misadventure and fairy-tale delirium, with echoes of Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe. Though it became a classic of children’s literature in Germany and across the Continent, Baron Münchhausen is said to have been displeased with the satirical portrayal of him as a peddler of fish stories.