An Enigma Made Flesh: Delphine Seyrig in Golden Eighties

In the first half of her career, Delphine Seyrig seemed to float above reality. To watch her in films by Alain Resnais and Luis Buñuel is to feel hypnotized, to be compelled to reach out and touch her, only to grasp at thin air. It was not until almost fifteen years into her life in the spotlight that she was brought down to earth, by her stripped-down performance as the widowed housewife and part-time prostitute in Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). That role helped unshackle the actor from her ethereal persona, but it was her second collaboration with the Belgian filmmaker that truly set her free.

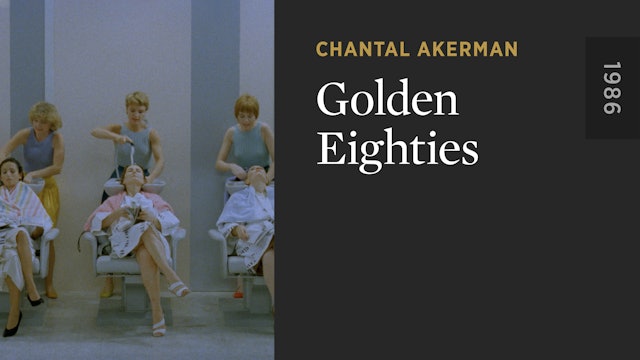

In the effervescent and bittersweet shopping-mall romance Golden Eighties, Seyrig plays another Jeanne—Jeanne Schwartz, a Jewish woman who runs a clothing store. Like Dielman, the character is a dutiful mother to a self-absorbed young man. The “patron saint of ready-to-wear” (per the film’s crooning mallrats, who serve as a kind of Greek chorus throughout the film), she carries on with a graceful resilience, dodging her ghosts as best she can by keeping busy with repetitive retail work—adjusting the same mannequin, opening and closing shop. But this time, Akerman had written a Jeanne for Seyrig from an alternate universe steeped in pop aesthetics and the excessive, intuitively expressive qualities of music—a far cry from the durational rigor and forceful materiality of Jeanne Dielman. This Jeanne not only speaks, she sings.

Perhaps this performance, in which Jeanne is struck silly by the return of a past lover, would not feel so remarkable—so cathartic—were the roles that had defined Seyrig up to that point not bound to a certain aloof mystique and sense of enchantment, qualities forged in large part by the awestruck male directors with whom she initially worked. Surely her seraphic screen persona was a natural extension of her urbane bearing, her breathy voice, and its beguiling lilt. But she was always more than this, and she knew it; she was deeply opinionated, sensitive to the world around her. For a while, she was a projection of other people’s desires, yet it was when she began to explore her own that she was at her most dazzling.

Born in Beirut in 1932, the daughter of French and Swiss intellectuals, Seyrig had committed to being a serious actor by her twenties. At the time, she was married to an American painter and living in Manhattan, where the art scene—though not yet the film scene—was hot. Her bohemian milieu, which put her in the company of abstractionists and Beat Generation poets and Actors Studio hotshots, allowed her to eventually cross paths with Resnais, who then cast her, at age twenty-eight, in her first major role, as the nameless woman at the heart of Last Year at Marienbad (1961).

Amid the film’s ghoulish extravagance, its baroque interiors and funereal organ score, its scatty editing rhythms and angular, black-and-white tableaux, Seyrig emerges as an object of extraordinary fascination. Picture her now, stepping out from the shadows of a blackened hallway onto a sliver of light on a checkered floor, her white skin electric, her image doubled in the rococo mirrors scattered around the purgatorial estate or gliding aimlessly through its sculpted gardens. Her downward gaze and fluttering eyelashes pull you into her mystery, and when you finally lock eyes with her, she might look at you as if she knows your most intimate secrets—or as if you don’t exist.

Marienbad made her a star—la divine to the critics, muse to a cohort of auteurs—while her short, slicked-back coiffure and fetching Chanel costumes unleashed a novel look that would captivate the demoiselles of a new generation. Modern though she was, her appeal was also rooted in an archaic kind of goddess-worship, creating a straight line between her and sphinxlike stars of classic cinema like Greta Garbo or Louise Brooks. Like them, Seyrig mystified and seduced, and over the following decade many of the directors she collaborated with would play upon this enigmatic persona, giving her roles that allowed her to deepen and complicate it with layers of self-awareness, if not outright self-parody. She went on to play the woman of Antoine Doinel’s dreams in François Truffaut’s Stolen Kisses (1968), the fairy godmother to Catherine Deneuve in Jacques Demy’s Donkey Skin (1970), the spellbinding Countess Báthory in Harry Kümel’s erotic vampire film Daughters of Darkness (1971). “I’m not an apparition, I’m a woman,” she tells the lovelorn Doinel before initiating their one and only tryst—a fulfillment of his fantasies, even if she is exerting her own flesh-and-blood reality in the process.

Seyrig—whose earliest role models, thanks to her parents’ worldly friends, were women globetrotters and flapper types—came to despise her success, or rather the limitations upon which it was based. “I became a sort of status symbol—hired to create a link with another great director and not a choice for myself,” she said. She was hardly a docile collaborator; together with Jane Fonda, her costar in a 1973 adaptation of A Doll’s House, she railed against what she perceived as director Joseph Losey’s misogynist revisions of a fiercely feminist text. But her image, rather nightmarishly, came to embody what she was not: an unknowable woman. This she would ultimately reject; Delphine Seyrig would make herself known.

Seyrig’s creative partnership with Akerman changed everything. By the time the two met in 1974, the actor’s political convictions had become a top priority, and so too had her commitment to making feminist art. These undertakings, anchored in the desire to create true and emancipatory forms of female expression, are exemplified by the women’s most well-known films—Jeanne Dielman and Golden Eighties—albeit in radically different ways. In Jeanne Dielman, the camera is obsessed with Seyrig, her micro-expressions, her every move. The sum of the film’s non-events creates a kind of drama from the textures of Jeanne’s daily life, with the rhythms of her physicality communicating her interiority even more effectively than her words. But Seyrig questioned Akerman’s unrelenting formalism. Her movements mapped out to a T, and instructed to perform with extreme reticence, Seyrig was denied a more collaborative role. “I have no room to be creative here, the script is so specific,” said Seyrig in Autour de Jeanne Dielman, a documentary about the making of the film. This lack of creative freedom must have felt suffocating to Seyrig. She was newly accustomed to voicing her beliefs, after her turn to public activism as well as her directorial work with Carole Rousopoulos, with whom she formed the radical film collective Les insoumuses (or “disobedient muses”).