RELATED ARTICLE

Among Friends: A Chat with the Directors of Feast of the Epiphany

By Andrew Chan

The Criterion Collection

The house on Walnut Road was and still is, among other things, a movie house. That becomes vividly clear in Michael Koresky’s searching and tender new memoir, Films of Endearment, in which he returns to this beloved childhood home several times over the course of sixteen months for a cinematic experiment. With his mother, he set out to watch ten films from the 1980s that she introduced to him when he was a kid, all of them featuring women as protagonists. The result is a revitalization of the act of rewatching—not merely an exercise in nostalgia, but a sizing up of the self, the mother, her story, and what lies beyond the threshold of the past.

In the book, the Koresky house—a two-floor Cape Cod with walls of books and a piano collecting dust—functions both as a setting and a portal to other houses, the ones lived in by the characters Michael and his mother encounter on-screen. It’s often the smallest details of those homes that linger in the memory long after the movies are over, and these interiors helped him develop a heightened sense of space, domestic comforts, and families navigating their zones. Films of Endearment also shows Koresky’s eye for great acting, from Jane Fonda’s ever-changing performances to Whoopi Goldberg’s quick-witted character studies to Debra Winger’s hoarse yet gentle mannerisms.

Shortly before the release of the memoir, I spoke with the author—who, in addition to his writing and filmmaking, works as the editorial director at New York’s Museum of the Moving Image—about what he took away from this emotional journey into the past and what he learned about his mother along the way.

Has this been a project you always knew you were going to write, or was it one that seemed to pick up in momentum at a certain point in your life, based on patterns you started noticing in your own criticism?

So many little things happen along the way when you’re a writer. Things that you don’t expect. As a writer, you don’t really understand what your voice is, or who you’re writing for, or why you’re writing, for such a long period of time, right? In my case, it was clearly film. I’ve been obsessed with it from an early age, and I also loved writing short stories as a kid, so I knew these two things would come together in some semblance of a career.

As the years have gone on, I’ve gone through some different realizations about myself. I went through many years of eradicating “I”—like it was somehow crass or crude to bring myself into my writing. There was a turning point where I wrote a feature for Film Comment that was about the history of this magazine called Films and Filming. It’s a British film magazine that existed from the fifties to about 1980. Anyone in the know—meaning queer people—could tell that this was, basically, a gay magazine. I realized, how can I write about this if it’s not also about me and my gradual realization of my queerness? The fact that I was able to harness that within this history piece made me realize that I could bring the “I” voice into it more.

The book came bit by bit. At one point in 2018, my husband and I were watching Steel Magnolias. It was on some streaming service, and we were just relaxing with a glass of wine, and I actually realized at that point, “Oh my goodness, I watched this movie so much as a kid.” My brother was off watching Terminator a million times, but I was watching Steel Magnolias. And there can be that kind of knee-jerk, “Oh, you knew you were gay at that point” that happens in our culture, where you’re kind of denigrated for your queerness with these non-masculine objects. It’s then that I thought, there’s something worth investigating. And then, when my mother told me that the ’80s were her most important decade, something clicked in my head. There were these two things that were coming together: my realization of what mattered to me as a child watching movies in the ’80s, and my realization that she was having these revelatory experiences with movies at the same time.

How much is your relationship to your mother inextricable from your relationship to film?

Certain things were exorcised in working on this that I hadn’t come to terms with or thought about, which is this question of where taste comes from, and why I have this close connection in my mind to the movies and my mother. It’s a validation of her.

Has she read it?

She has, because she was the fact-checker.

Of course.

It comes across as a love letter, I’m sure, in many ways, but there are some challenging things in there. There are some ways of dealing with questions around death and loss and just, um, sexuality that are a little uncomfortable. She was the most important fact-checker because I got a lot wrong. I was taking furious notes and recording conversations; sometimes she wasn’t fully aware that I was recording conversations. I would get notes from her, and I would love hearing that I got things wrong. It showed me that I just still don’t know everything that I think I know. The people who are closest to us—we try to narrativize their lives. We’re never going to see it through their eyes. And that was an important thing for me to go through in writing this, because as a film writer, I’m so used to writing on things that you can see.

Let’s keep talking about the idea of getting things wrong. What was your experience of rewatching certain movies in order to write this book like?

It was an experience of trying to see it through someone else’s eyes. When I’m watching 9 to 5, every time that scene comes up—and I talk about this right at the beginning of the book—where Dabney Coleman calls Lily Tomlin, Jane Fonda, and Dolly Parton “dumb-witted broads,” I think of my mother telling me, “You are never to say that to a woman.” I can’t watch The Color Purple without thinking about the way it made my mother cry. These movies are particularly special because they don’t exist independently of her. The book is a distillation of my entire experience with film across the board. Because no matter what I’m doing, I’m seeing the world through my mother’s eyes, and how do I come to terms with that? Where do I draw the line? Where do I start?

How much of yourself do you see as your mother’s son?

My mother and I are really different in a lot of ways. She is a performer. She’s extroverted. She tells it like it is. She’s not scared of anybody. And I’m not like that at all. I’m terrified of performing. Terrified of speaking in public. I’m terrified of putting myself under the spotlight. I know this doesn’t speak for everybody, but part of that in my case has to do with my gayness, and has to do with the fact that when you’re closeted for such a big part of your life, you get terrified of the spotlight. When I was young, I hated going to high school. I would look at my cats in the morning before leaving the house, and they would be all curled up in a little crevice somewhere, and I would be so jealous of them.

What amazes me about my mom is she had all these jobs, and she’s had two sons. She’s dealt with the death of a husband. She soldiers through it all. She just never backs down. She tells telemarketers to fuck off. She tells people on line at the supermarket to get out of her way. She just isn’t me. That’s one of the reasons that I felt that this would be a helpful project. Like, what are the things that unite us and what are the things that separate us? I am an audience member, and though I think that she loves to watch and she’s a great viewer, she’s at heart a performer.

Listening to you describe your mom, she has all the qualities of a real character—someone who might inspire a character in a movie.

The question becomes, who do you cast?

Have you thought about that ever?

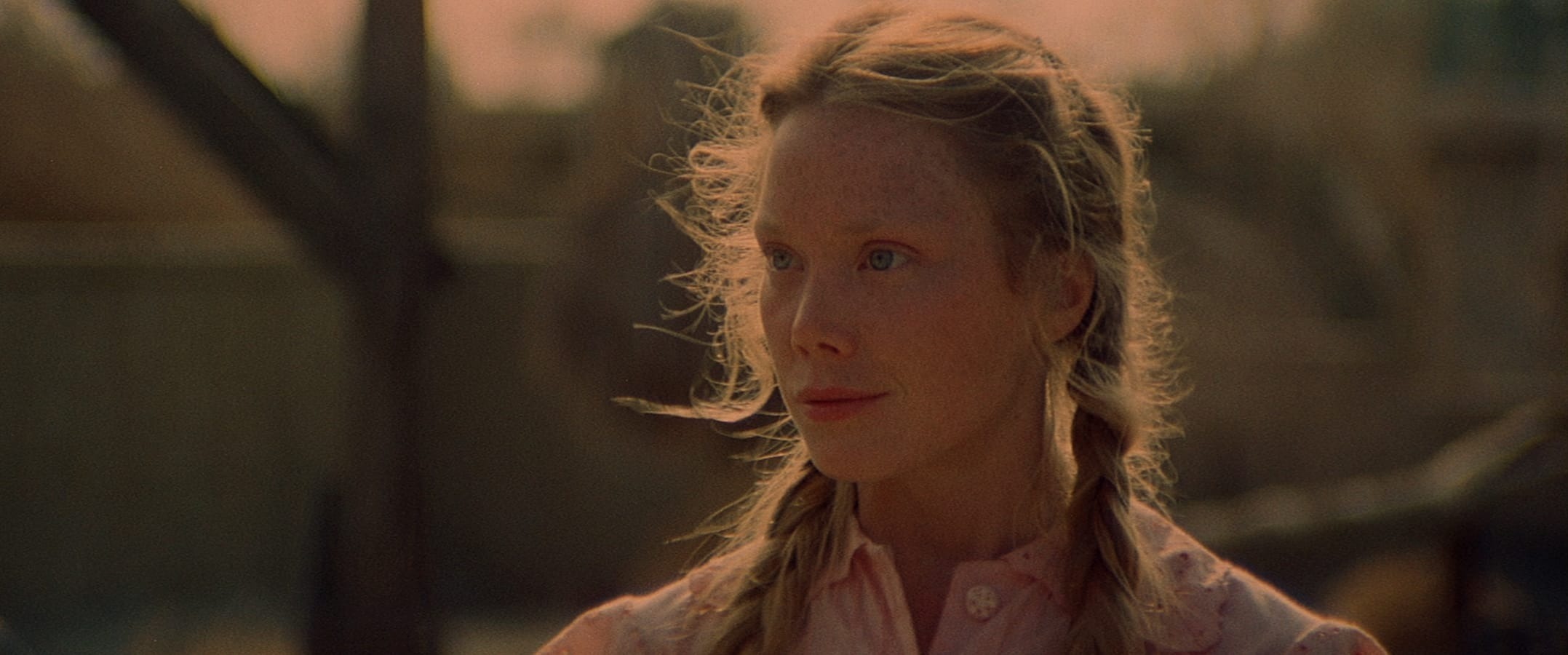

I actually never have, which is crazy. Julianne Moore? Which is funny, because she often plays very demure people. But every once in a while, she’ll play this kind of ballsy, extroverted character, and I’ll say, “That’s her! That’s my mom!” My mom also used to have red hair. Sissy Spacek, too. She’s absolutely my favorite. I’d watch her do anything. I would go to the ends of the earth for her, even though I’ve never met her. But Sissy Spacek is so culturally different from my mom. She’s incredibly Southwestern and authentic and amazing, and my mom is this New England Jewish woman who grew up in a city.

If you could program your dream Sissy double feature, what would you pick and why?

3 Women and ’night, Mother. What you see in those two movies is her ability to strip herself completely bare, and while those two films are pretty raw, I think watching them back-to-back, you’ll never again doubt the sheer power of her authenticity, of her ability to bore through the screen with that face.

I kept thinking of Amy Madigan, actually, when “casting” your mother.

Oh! That’s a great one.

I love her. In Field of Dreams, she played such an idealist, so hopeful.

When she gets into a fight with the book-burning Nazi woman, that’s imprinted on my brain.

That scene is so good. And then she slides into the high school hallway and bangs her fist against the lockers, and shadowboxes. She’s just electric.

That scene made a very, very big impression on me as a kid. I’m seeing it right now. Like she could take on the world. And then I discovered her and Ed Harris are this great activist couple.

You really care about the impact of specific seconds of a film. Has that always been how you fall under the influence of film? Little scenes that alter you forever, like you don’t remember living before experiencing them?

Yes, of course. I am affected by scenes that way. I am affected by the macro as well. When I think of the totalizing force of cinema, when I think of some of the great films that mean so, so much to me, of course I think of them as these overwhelming behemoths that bear down on me, and I can’t get away from them. When I think of Vertigo, I think of that monstrous thing that just can’t get out of my brain. I’ve had nightmares about Vertigo! I’ve had nightmares where I’m being attacked by the Carlotta portrait. It’s not fun—it’s scary! I’m talking about waking up with my face just in utter panic. There are just scenes and segments that I cannot get out of my head. And I think it’s as simple as the way an intonation is spoken, or the way a word is spoken, or obviously the way the camera is used in a certain moment. I think that what good film criticism does for the writer is help put definitions on that. It helps you understand exactly what it is you’re seeing, how it’s working on you emotionally.

I’m similar to you in that I don’t know who I would be without certain movies, and I also don’t know who I would be without certain performances in certain movies. I’m curious, though: were there films that you feel you were supposed to like or supposed to obviously relate to growing up, but you didn’t?

I have an interesting instant reaction to that, and it’s connected to my mom. For the most part, movies that are deemed great always have a lot to recommend for them, and you can convince yourself that it’s a masterpiece, and just go along. I never liked Blue Velvet. I like David Lynch. I think Mulholland Drive is probably one of the twenty or thirty greatest movies of all time. But I do not like Blue Velvet; I’ve never connected to it; I feel nothing when I watch it. I don’t even like it aesthetically. I don’t like it philosophically. It has this central misogyny to it that I felt at a very early age. And I realized that that reaction came from my mom. My mom had rented Blue Velvet, and I wasn’t allowed to watch it; I was too young for it. But she talked about it a lot; she said, “Ugh, that Blue Velvet, I don’t like the way that movie treated Isabella Rossellini.” Because there’s a lot of degradation, there’s nudity, and there’s a lot of humiliation. And she really felt it deeply. She was really repulsed by it. And I hadn’t seen it until years later, and I couldn’t get out of my head my mother’s reaction to it.

What else?

I think it was very easy for me to feel alienated by movies that were uber-masculine, and it happened a lot to me as a kid. My brother was much more into the testosterone ’80s movies, which a lot of people think of when they think of that era, before they think of women-centered movies. You know the movie Twins, with Danny DeVito?

Yes.

It’s a good example of a movie that the culture was telling me I was supposed to like for some reason. I saw it a bunch when I was a kid without ever being able to connect to it. The central conceit of it, how we’re supposed to find the inherent height difference funny . . . that’s not inherently funny! I don’t know why that’s funny.

Few things are as disorienting as someone saying, “Laugh at this joke.” And you can’t laugh.

Completely. And then there’s the sense that what you’re feeling is somehow culturally incorrect.

Let’s try a few more double features with leading actresses you mention in your book. Jane Fonda.

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? and 9 to 5. Because that’s just a shocking contrast. I keep picking movies about suicides. Why do I do that? They Shoot Horses is one of the most despairing films ever made. I think charting that kind of progress from ’69 to ’80 is pretty exciting. Like two good bookends.

What about Sally Field?

Norma Rae and Steel Magnolias. Because Norma Rae shows off the kind of spitfire, politically driven heroine of the ’70s—it’s kind of the perfect film of that sort. And then ten years later, she does Steel Magnolias, and it’s astonishing to me that that’s only ten years, because she’s like a quintessential mom to Julia Roberts. Sally Field’s funeral scene is something that affected me very profoundly as a kid. The way that she screams, “Why?” is so risky, so ballsy. It could go so wrong. But it feels so completely wrenched from the pit of her soul.

And now, Cher.

Silkwood and The Witches of Eastwick. It seems like I tactically left Moonstruck off. But for whatever reason, we each have our own more personal connections to things. Witches of Eastwick I’ve just seen so many times, and I absolutely adore the kind of subversive sisterhood of that movie, and it’s something that I was always jealous of and aspired to. Silkwood is just an excellent movie. The fact that she dove into playing a lesbian character at that point in Hollywood history, when it just wasn’t being done, and a character and a performance completely without stereotyping, blows my mind. I really love that character, and her relationship with Meryl Streep in that movie is pretty special, and I don’t think you can find anything from the era that comes close.

What does the word cinematic mean to you?

It’s one of those words that would be good to start using with a little more judiciousness. The more you dig into cinema, know more about cinema, live with cinema, “cinematic” feels like something that’s wielded both for and against the art form, especially at a moment where there are just endless, pointless debates about what is cinema and what is television, and those lines being so blurred. I think you call something made for television “cinematic” and that ultimately devalues both television and cinema, right? So, I don’t know what it means anymore. Jeanne Dielman is one of the most cinematic films ever made, if you want to use that term. If you want to think of it as something that works on you in a cinema, maybe that’s one way of defining it—and then there is no greater film than Jeanne Dielman, right? You shouldn’t be able to pause it. You should be uncomfortable; you should be stuck in that small space; you should be with other people who are experiencing it. You should be experiencing the quiet.

There’s that famous Kiarostami quote about how he prefers movies that put you to sleep. From his point of view, that’s cinematic, the ones that wake you up in the night and trail you. I probably use the word cinematic when I’m not talking about movies at all. The last time I felt something was cinematic—and it might have been a couple years ago—was when I was having a regular Sunday dinner with family, and my brothers’ babies were running around, and it was just chaotic in the house, and my dad was cooking, and my stepmom was carrying plates and food to the back porch. The movement in the house and the loudness and the chaos—I’m pretty sure I remember thinking, even out loud, “This is one of the best days of my life.” And in my mind, that’s cinematic. Close to it.

I love hearing that, because I write in the book a little bit about how I’m sort of envious of big, bustling, bursting families with lots of movement and noise and kids and color, and I don’t have that in my life. I think what we take from our childhood tends to be the thing that we think is most cinematic. What we take from our past. So for me, it’s those evenings in the house with my mom, drinking a glass of wine at the dining room table. You can see the sun going down outside, so there’s a little bit of a blue cast on the lawn. There’s a chandelier that’s in the dining room that gives off a nice yellow cast. The inside is very quiet, and there’s talking. That’s cinematic. That’s my connection. I see the world in that—through that kind of lens.

In this Sundance-award-winning exploration of war and memory, writer Cathy Linh Che shines a spotlight on her parents, who were Vietnamese refugees living in the Philippines when they were cast as extras in Apocalypse Now.

In her intensely personal debut feature, the filmmaker and poet investigates the myths that have shaped South African history through a mix of archival footage, poetic remembrances, and conversations with friends and family.

The director of the documentary Celluloid Underground discusses his life as a curator, Iranian film culture, and the inherent ephemerality of cinema.

From Grosse Pointe Blank to Singles to Trainspotting, some of the decade’s most memorable fusions of music and cinema brought underground culture to new heights of pop consciousness.