Home Is Where the Struggle Is: Victoria Keith’s Activist Lens in The Sand Island Story

THE LIFE OF THE LAND

one of the protest signs depicted (poetically, upside down) in The Sand Island Story

IS PERPETUATED

IN RIGHTEOUSNESS

Victoria Keith was a high school teacher, in 1976, when she heard about the pending eviction of two farming communities on Oahu’s East Shore. The struggle in Waihole-Waikane was personal to her, “because a lot of my students were from there,” she recently told me. She and her partner, Jerry Rochford, borrowed camera equipment from the school district and went out to interview longtime residents protesting their displacement. Making that first, black-and-white documentary, Two Green Valleys (available on YouTube), set Keith on course. From then on, she was a filmmaker first and everything else second. She worked stints as a teacher, a community college instructor, and a camera operator for a local TV news station (she was the first woman in this role at KGMB) to bankroll her films and feed her two daughters. Over three decades, she made more than a dozen documentaries that showed on public television and in community centers and schools, most of them about the heritage and land struggles of Native Hawaiians.

It’s hard to imagine someone like Keith—a white woman and a neophyte chronicler of Indigenous society—doing this work today baggage-free. For reasons that are mostly fair, this kind of cross-cultural advocacy is often frowned upon as acquisitive or reduced to a performance of white allyship. But Keith is an activist and a sympathizer; an oral historian, not an opportunist. “We never intended to represent the Hawaiian community,” she has said.

In her radical honesty, Keith makes herself visible, or at least audible, as a filmmaker. She narrates, asks questions offscreen, or wields a large foam-covered microphone on-screen. But there’s a moment in her best documentary, The Sand Island Story (1981)—which aired nationally on PBS in 1982, and is now playing as a selection of the Honolulu Museum of Art’s Doris Duke Theatre, in the Art-House American program on the Criterion Channel—that also reveals her willingness to get out of the way. A middle-aged fisherman in a yellow tank top and a baseball cap sits for an interview as his friends unload a boat behind him. (No one in the film is named or identified.) The water is ever-present as backdrop and soundtrack.

Keith begins with a leading question: “How would you feel if they moved everybody out of here and put everyone in apartments, in the city?”

“I’ll tell you frankly, lady, I wouldn’t be living that long. My life right there would be cut short,” he says.

“You mean, you would, almost . . .,” she tries to clarify.

“My life. Would be. Cut short,” he says again. “I wouldn’t have pleasure in the water, the way we live in the outside, in the city over there. My life wouldn’t be enjoyed.”

The man tells Keith that he needs no rewording—that he can deliver his own story. And she listens.

This twenty-seven-minute film documents four dramatic months on Sand Island, a fist-shaped parcel of land in Honolulu Harbor. The island had been neglected, or abused, in the colonial history of Hawaii, including as a site for Japanese internment and a dumping ground for industrial waste. In the 1970s, more than a hundred Native people who were otherwise homeless—kicked out of urban rentals or fed up with state-designated Native “homesteads” on rocky plots far from the sea—settled part of the island. They lived in trailers, plywood shelters, and stilt houses perched over the water. They fished as their kupuna did and taught their children the old ways of being. But they had no legal deed, even to this undesirable public land.

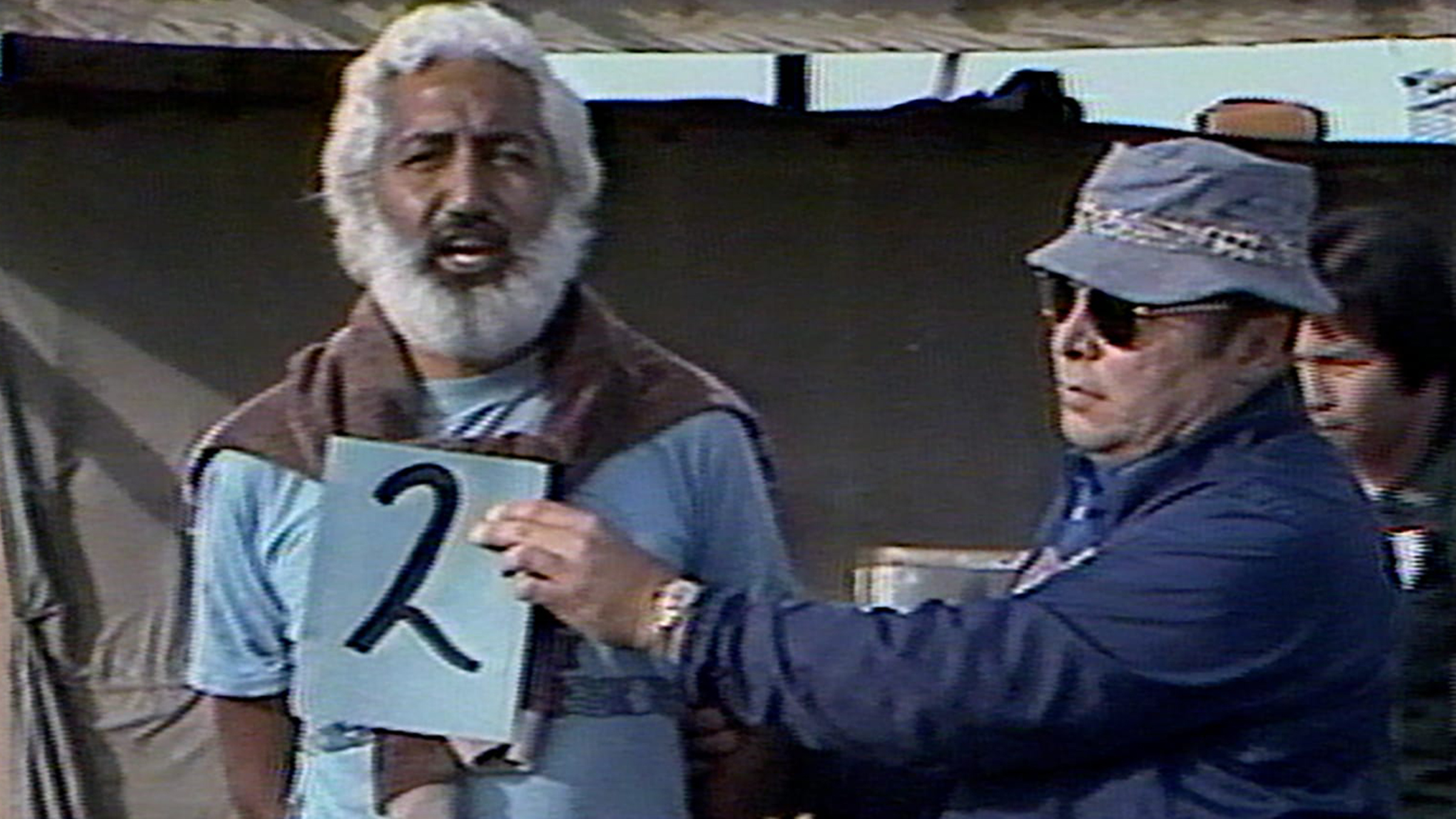

Sand Island Story begins with a man singing and playing guitar over peaceful footage of the settlement and sea. “In the midst / of all this garbage / Mother Nature made my home,” he croons. Then we hear the terrible growl of airplanes and a bulldozer running over the planks of someone’s home. A leader of the community, a handsome man with a full white beard, is dragged out of a structure in handcuffs. A plainclothes cop holds a “2” sign to the man’s chest for a photo. “Dogs in our own country,” the man says. “This is how you treat Hawaiians, ladies and gentlemen. Throw them in jail, knock down their homes, kill their culture, and eliminate the Hawaiian race.”

The remainder of the documentary covers the doomed months leading up to this destruction, when residents organized against the eviction, donning SAVE SAND ISLAND T-shirts and seeking relief in court. The handcuffed man, I learned later, is Abe “Puhipau” Ahmad, who appears in the credits for narrating an early section of the film. Keith had met Puhipau at a community meeting, before she did any filming on Sand Island. “I introduced myself and asked permission. I told them what we wanted to do,” she explained. “As it turned out, Abe was the father of three young teenage boys who had been my students just a couple years before.”