RELATED ARTICLE

Bridging the Gaps in Trans History: A Conversation with K. J. Rawson

The Criterion Collection

A film that centers on a transgender person or storyline enters the culture like any other movie. The difference lies in the discourse around it. A pervasive disregard for the realities of trans experience beyond the screen is evident in how criticism of such films is written, in how moviegoers view them, and even in how they’re made. Trans bodies have long been depicted in cinema in the most salacious and deviant contexts, and this has been met without much protest from the mainstream society that absorbs those images. Trans people in movies are written and talked about as if they were abstract concepts, anomalies. For years, it’s been clear that very little attention is being paid (by filmmakers, critics, or marketers) to the ways in which a trans audience might see and react to these attempts at putting their lives in front of the camera, and the cisgender majority continues to control the conversation. But a robust dialogue about these films has existed for decades within the trans community—it’s just gone unnoticed by the general public.

There is a false presumption that little trans history exists on record, that the trans experience is some neat trend of the present. Part of that is willful ignorance; another factor is that the archive of transgender lives is largely made up of works never meant to be consumed by the masses. The internet has been key in counteracting inaccurate narratives by bringing about a sea change for transgender archives and bridging the digital and the pre-internet worlds. There are numerous collections of trans history—including the largest in the world, the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada; the Human Sexuality Collection at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York; the ONE Archives Foundation at the University of Southern California; and the National Transgender Library & Archive at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor—each with its own repositories of letters, diaries, magazines, photographs, do-it-yourself zines, newspaper clippings, and audio. There are also several nonprofits and individuals with their own holdings and projects.

What has been most crucial in recent years is the integration of these archives for research purposes. Central to that effort is the Digital Transgender Archive (DTA), an initiative that started at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and will soon relocate to Boston’s Northeastern University. In the past, trying to uncover what was available in individual archives often proved to be a tall order for trans researchers. The DTA brings together collections from around the world, centralizing a marginalized community’s scattered histories within a single search engine. It has created an incredible opportunity to investigate, whether as a researcher or as an amateur, how trans communities of the past wrote about and expressed their experiences, and also how they responded to the moments when mainstream society looked back at them.

Some of the most valuable and insightful access points to trans history found on the DTA are magazines published in the latter half of the twentieth century. Exclusively transgender publications date back to the pre-Stonewall 1960s. Virginia Prince, a trans woman from Southern California who led a support group, self-published Transvestia magazine starting in 1960, and it was one of the earliest and most popular of these publications. Prince and others in her generation belonged to a wave of trans pioneers who emerged after Christine Jorgensen, a transgender American woman, gained global attention for her gender confirmation surgery in 1952.

These American trans publications of the 1960s and ’70s—self-published magazines and newsletters that are estimated to number around two dozen—were juggling an array of functions, responding to the needs of an eager readership looking for community and a better sense of what was out there, and who else was out there. Very early on, these publications were aware of how the outside world saw them, and those bigoted views meant that the majority were available exclusively in adult bookstores. Still, most of the publications could not be dismissed or labeled as smut, although there was certainly a cis male readership who also bought them because of fetishistic, prurient fascination.

Contained within their pages was medical news, as trans surgeries were beginning to take place in the United States; for example, Dr. Harry Benjamin’s The Transsexual Phenomenon, published in 1966, gave readers official scientific affirmation that “sex changes” were happening domestically and were not just available to those Americans, like Jorgensen, who were willing and able to travel abroad. There were also bulletins on other issues that concerned the community; sections in which readers could communicate with pen pals; “Dear Abby”–like advice columns; and photo shoots depicting everyone from anonymous trans women to internationally known French entertainers like Bambi and Coccinelle.

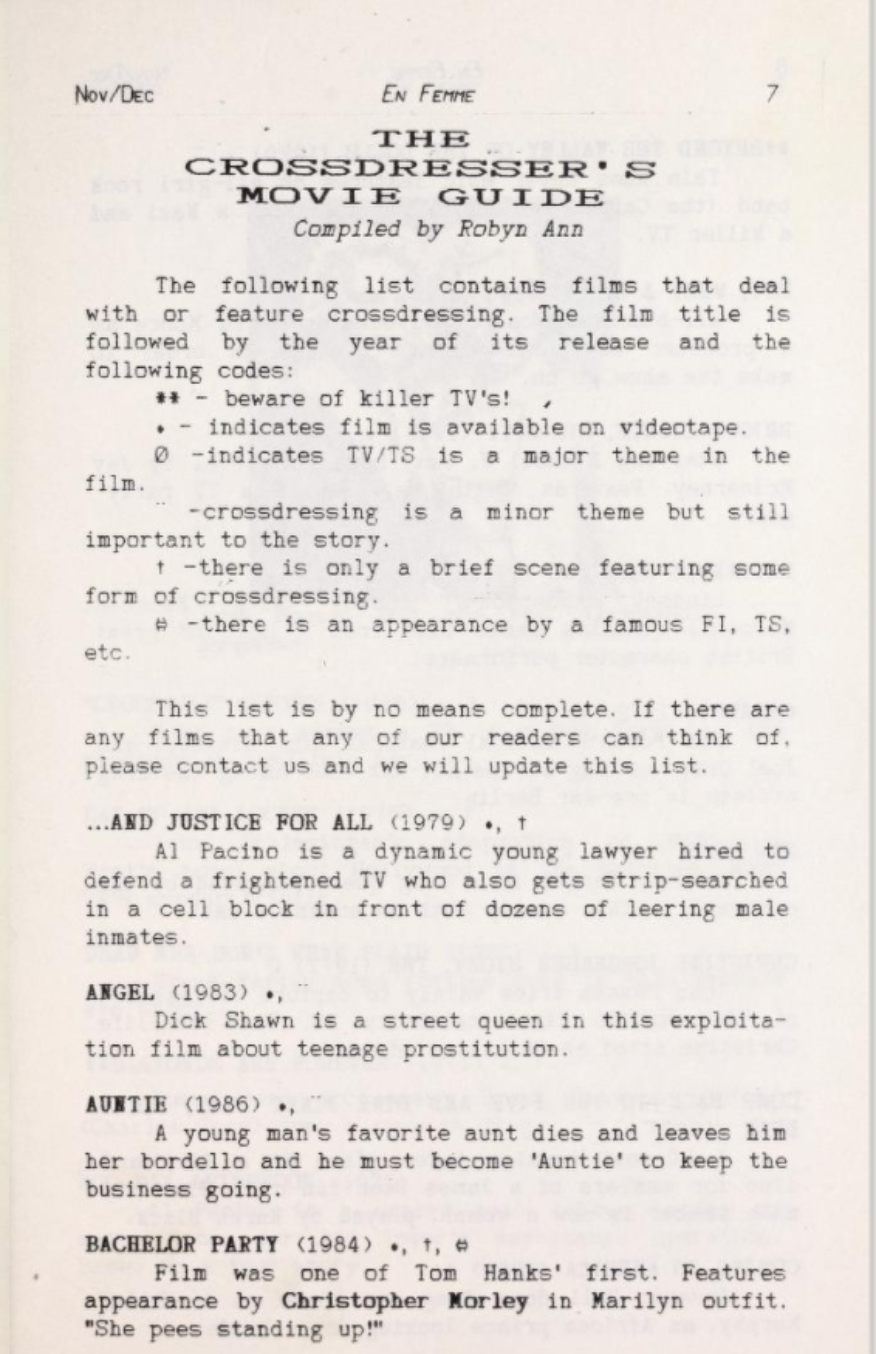

Also featured were spaces to talk about movies. Films with trans people or cross-dressers had the community on notice and generated consistent coverage. Just the mere presence of a trans character, however brief, could provoke a review or an editor’s note. There was commentary about Toshio Matsumoto’s 1969 Funeral Parade of Roses (in the publication DRAG: A Magazine About the Transvestite) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1978 In a Year with 13 Moons (in Les Girls) upon their release in the U.S., and a few publications collected lists and tracked relevant films, offering guidebooks with short capsules. The scarcity of trans images inspired some publications to promote Super 8 reels of known trans performers for purchase.