Feeding the Appetites: Nan Goldin’s Movie Obsessions

In the four decades since she began her career in Boston as a photographer, Nan Goldin has used her own life as the narrative arc of an ever-evolving body of work. Searing in their intimacy and deeply influenced by cinema, her color-saturated photographs document her world and the friends and lovers in her circle, depicting the dramas of relationships both affectionate and abusive, the everyday lives of the LGBT community she has long been closely associated with, and the harrowing realities of the AIDS epidemic and the opioid crisis. Goldin remains most famous for The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a series of 700 photographic portraits that she originally presented at underground venues like New York’s Mudd Club as an improvised live performance and slideshow, set to the music of the Velvet Underground and Maria Callas. When the project was shown at the 1985 Whitney Biennial, Goldin became an art-world star. But while she has earned her place in the canon of American photography, she has long dreamed of becoming a filmmaker.

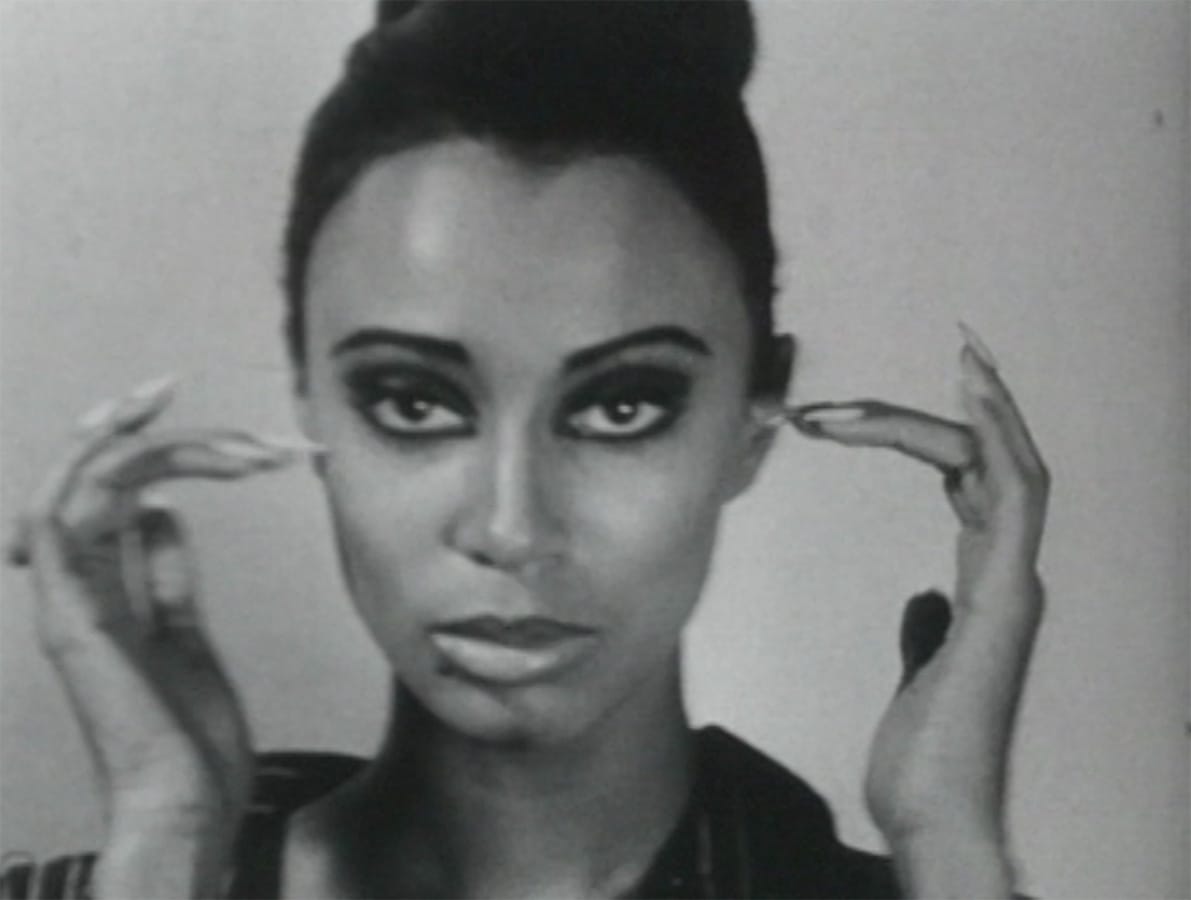

This summer, New York’s Metrograph theater put the spotlight on Goldin’s recent film and video work, presenting the digital debut of her found-footage short Sirens and making her the first guest curator of its new streaming platform, where she programmed personal favorite films by Vivienne Dick and Michael Roemer. An exploration of the ecstatic pleasures of addiction, Sirens is an assemblage of clips from the work of Jack Smith, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Kenneth Anger, Lynne Ramsay, Michelangelo Antonioni, and other filmmakers, woven together by Mica Levi’s haunting score. Just as The Ballad metamorphosed over a period of time, so too has Sirens. A new, reedited version is coming to the Metrograph’s site this weekend, presented by Goldin alongside a secret film selection.

On the occasion of Sirens’ release, I got the chance to speak with the artist about her memories of moviegoing in a bygone era of New York and the ways that her lifelong passion for cinema has helped shape her vision.

Do you remember the first film that made you fall in love with the movies?

I saw Blow-Up for the first time when I was fifteen, and it’s why I decided to become a photographer. I have scenes from that movie embedded in my brain forever, especially the one with David Hemmings and Veruschka. Years later I photographed her, but it didn’t come close to that scene! I saw it with my father, who didn’t get it. Around that time I also saw Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, which was revelatory for me and still is every time I see it. I actually just saw it again two nights ago.

Did you go to the cinema often when you were growing up?

Yeah. I lived in a hippie commune and went to a free school. Basically we didn’t have classes, and we went to the cinema almost every day. In Cambridge there was the Brattle Theatre and the Orson Welles Cinema, which showed three movies at a time. I grew up on double features—I’m still not used to the single feature. We would also go to all-night screenings.

Cinema was the major art form in my life, and at that age I wanted to be a filmmaker when I grew up. I ended up doing photography because it was easier, and it’s taken me a long time to respect it as one of the serious mediums, like painting and filmmaking. I’ve never taken it as seriously. I think of my slideshows as films made of stills, and recently I’ve started working with moving images.

Do you see your film and video work now as an evolution of the Ballad of Sexual Dependency slideshows?

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is my magnum opus, and it continued to evolve from 1980 to 2015. I continually changed it, so I don’t see it as only historical—it’s a live work. I just did a major show in London where I presented three new pieces. One of them is a three-screen video piece on Salome with disco music, and another is called Memory Lost, which I hope to screen when Metrograph reopens. They’re companion pieces: Sirens is about the pleasure and euphoria of drugs, and Memory Lost is about the darkness of addiction. I have another analog slideshow called The Other Side, which is related to the book of the same name and features drag queens and trans people I’ve lived with since the seventies and up until 2011.

I’d love to know more about your early days in New York. What was your experience of the downtown film scene like?

When I moved to New York in 1978, it was the week the Mudd Club opened, and that scene was very much alive. People were also showing each other their films at St. Marks Cinema and Theater 80, which was another venue on St. Marks. One week it would be Vivienne Dick, another it would be John Lurie and James Nares or Eric Mitchell or Amos Poe. Some of the films were works in progress and we’d see them in different edits over time. The audience was made up of people who were in the films, like Lydia Lunch and James White of the Contortions. That was a big part of my life at the time. Then there was a place called the O-P Screening Room, run by a man named Rafik, and that’s where I first started showing The Ballad. Jack Smith had a night there, and Vivienne showed there. That continued until the mid-eighties.

In the series you put together for Metrograph, you programmed two of Vivienne Dick’s films, Liberty’s Booty and Beauty Becomes the Beast, alongside Sirens. I’m curious about the connection between her work and yours.

I would have never made The Ballad without Vivienne. She showed me a whole new way of making work and taught me about the relationship between music and editing. I started using slides as a way to show my work and editing music segments together as a narrative voice. She opened me up to that. Her work is seemingly so fragmented and visceral but is still very tightly done. Her films are never didactic, even when they are dealing with topics like prostitution or childhood trauma. She’s someone who works out her struggles in her films. I love to see somebody’s psyche on the screen. She also gives one of the truest views of the Lower East Side at the time, which everyone wants to imitate so badly now. And the people in the films were always her friends. Like The Ballad, her narratives are also driven by the music.

Variety

Sirens