RELATED ARTICLE

La Pointe Courte: How Agnès Varda “Invented” the New Wave

I’m Still Here: A Conversation with Agnès Varda

The Criterion Collection

It has taken me forty years to appreciate the audacity of Agnès Varda in writing and directing One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977). Not only did Varda make her subject the most crucial and vexed issue of the feminist movement, at that time as it is today—a woman’s right to control her body, specifically her reproductive system—she also fashioned a narrative that is as rife with contradictions and reversals as freedom struggles always are.

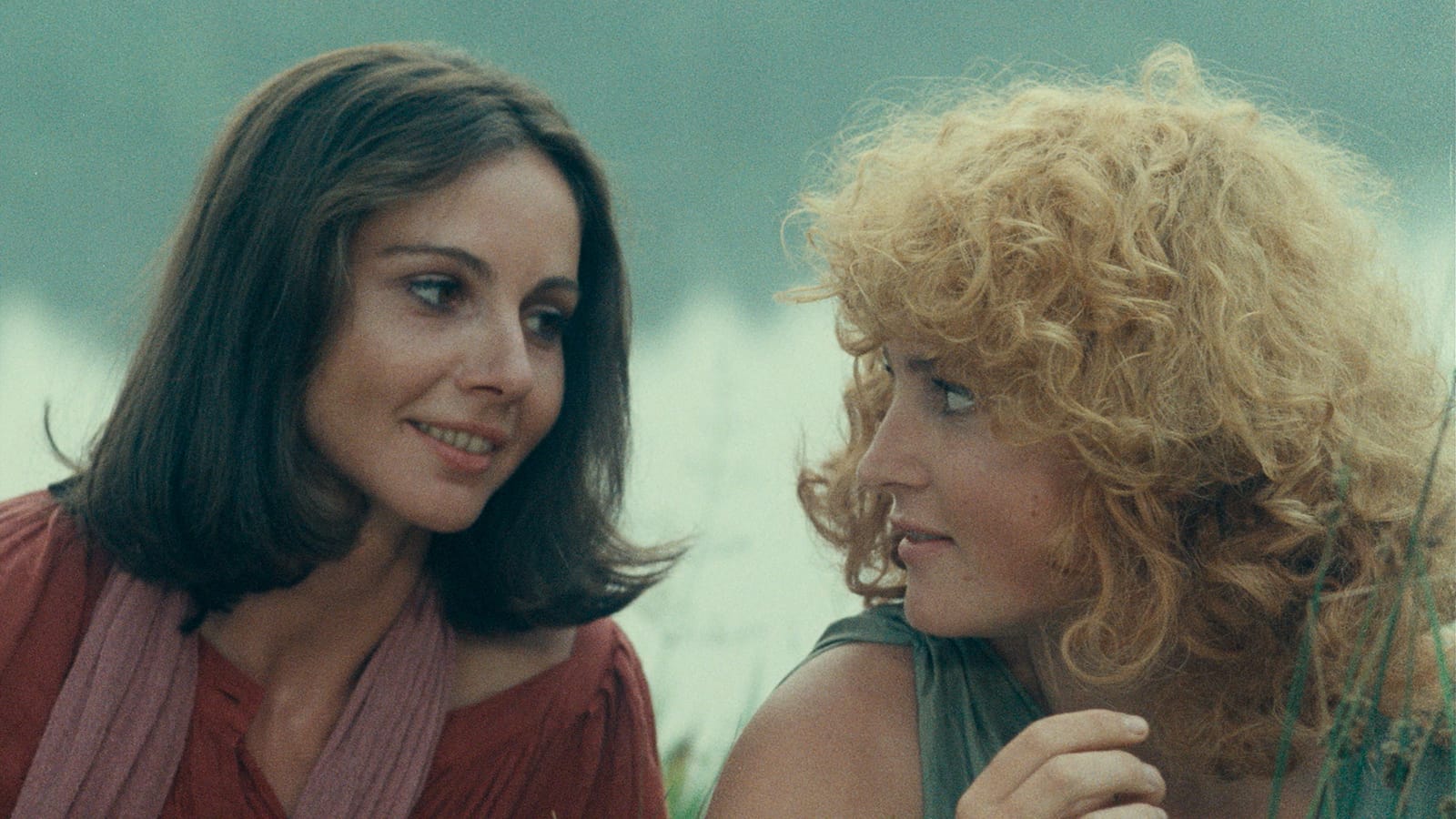

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t recounts, with guarded optimism, fourteen years of the women’s liberation movement through the story of a long friendship, often conducted via postcards, between two women, Pauline, a.k.a. Pomme (Valérie Mairesse), and Suzanne (Thérèse Liotard). While it is not an autobiographical film, Varda was certainly a participant in the coming to feminist consciousness in France that it evokes with considerable humor and a necessary dose of pathos. Born in Belgium in 1928, she grew up in the small French town of Sète, on the western edge of the Mediterranean coast. She studied art and philosophy in Paris, and in her early twenties became the stills photographer for Jean Vilar’s Théâtre national populaire (TNP), the leftist answer to the Comédie-Française. In 1954—for reasons she has always maintained were unclear to her except that she wanted to capture people’s voices and still photography couldn’t do that—she wrote and directed a feature film, La Pointe Courte, produced by her own company, Ciné-Tamaris, with which she has made all the subsequent features and short films of her sixty-five-year, enormously prolific career.

Independent feature filmmaking was unheard-of at the time in France, where most movies were produced by large companies or the two television channels. Aspiring directors, after graduating from film school, had to spend years as assistants to directors, producers, and editors before they were allowed to helm a movie on their own. At the time Varda was making La Pointe Courte, there were no other French female directors. Alice Guy-Blaché, who was a contemporary of Georges Méliès and the Lumière brothers and made more than a thousand films by 1920, had been written out of film history; the early feminist director, theorist, and critic Germaine Dulac’s filmmaking had ended by World War II. The male directors who would become the creators of the French New Wave were just beginning to make short films. Varda was friends with one of them, Alain Resnais, and he agreed to edit La Pointe Courte. She recruited two stars of the TNP to play a couple whose relationship nearly comes apart because the man wants them to stay in Sète while the woman wants them to go back to Paris—their conflict anticipating that of Pomme and Darius in One Sings, the Other Doesn’t.

Like the rest of the New Wave directors, Varda was influenced by the critic and theoretician André Bazin, who proposed that fiction films allow us to understand history—that the greatest of them are documents of the moment in which they are made, and that is the basis of their moral value as well. Varda, along with Jean-Luc Godard, radicalized Bazin’s position by openly mixing documentary and fictional elements, from the beginning of her career. The story of the couple from the city makes up only half of La Pointe Courte; the other half is a documentary-like portrait of the fishermen of the village, their families, and their struggle against government regulations that threaten their livelihood.

In the seven years between La Pointe Courte and her second feature, Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), Varda made several short films, including L’opéra Mouffe (1958), which she shot while she was pregnant with her daughter, Rosalie Varda. She has described L’opéra Mouffe as an autobiographical documentary, a projection of her own physical and psychological condition onto women she saw in the street. Combining documentary and fantasy images, it may be the first film by a woman to focus subjectively on women’s bodies. Similarly, Cléo from 5 to 7, which resembles many films by male New Wave directors in that its central character is a beautiful young woman, is unique in its depiction of its heroine as she awaits the result of a test for cancer. New Wave heroines were hardly immortal; they were often shot dead or killed in car crashes. But only Varda could read a series of newspaper articles in 1961 about women and cancer and understand that a movie about that issue and the terror around it would be as revolutionary for its subject matter as for the play of real time against subjective time hinted at in its title. And the fact that, for nearly sixty years, the critical response to Cléo has been to canonize it for its experiment in cinematic time while ignoring the story it tells confirms the need for the critique of patriarchy that the film provokes.

“Varda favors a mélange of blues, sea greens, and salmons.”

“The film embraces maternity while insisting that women must have the right to decide when or if to bear children.”