The Browning Version

Contemplating Anthony “Puffin” Asquith’s career, it is striking how self-effacing he eventually became, both as a filmmaker and as a personality. In the silent era, Asquith was every bit as flashy and inventive as his near contemporary Alfred Hitchcock. Shooting Stars (1927) and A Cottage on Dartmoor (1929) were both tempestuous melodramas into which Asquith threw bravura editing sequences, elaborate lighting effects, and quicksilver camera tricks. Like Hitchcock, he was clearly influenced both by the expressionist work done by Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau at UFA Studios in Germany and by the pioneering films and theories of the Soviet directors.

By the time he came to make The Browning Version, in 1951, much of the old flamboyance had gone. Whereas his directorial style in the silent era was all fireworks, the Asquith of later years was a far more unobtrusive and restrained filmmaker. His particular talent, he discovered after a stuttering start to his career in talkies, was adaptation. Asquith knew better than any other British filmmaker of his era how to turn the great plays of Oscar Wilde (The Importance of Being Earnest) and George Bernard Shaw (Pygmalion) into fluid, intelligent movies. He had a knack for keeping the camera still at the right moment and for capturing nuances in dialogue and performance, without allowing his films to seem stagy or hidebound. Like his earlier adaptations of Terence Rattigan plays (The Winslow Boy, While the Sun Shines), The Browning Version is bereft of heavy-handed directorial flourishes. There is next to no music save for a little Beethoven over the credits. The closest we come to an action sequence is a cricket match.

Asquith had wanted to make The Browning Version into a film from the moment he first saw the play, in 1949, but struggled to find backers. The material was considered too downbeat for the tastes of most potential financiers. After all, this was a study in repression and failure. The main character, Andrew Crocker-Harris, is a classics teacher at an English public school. He is a stickler for punctuality and a stern disciplinarian. Early on in the film, before we actually see him, we learn that this is Crocker-Harris’s last term. He is being forced into early retirement because of ill health. The schoolboys detest him. The Himmler of the Lower Fifth is their harshest nickname for the Crock. Rattigan based the character on one of his own teachers from his school days at Harrow: a dour and graceless man whose emotions seemed deep-frozen.

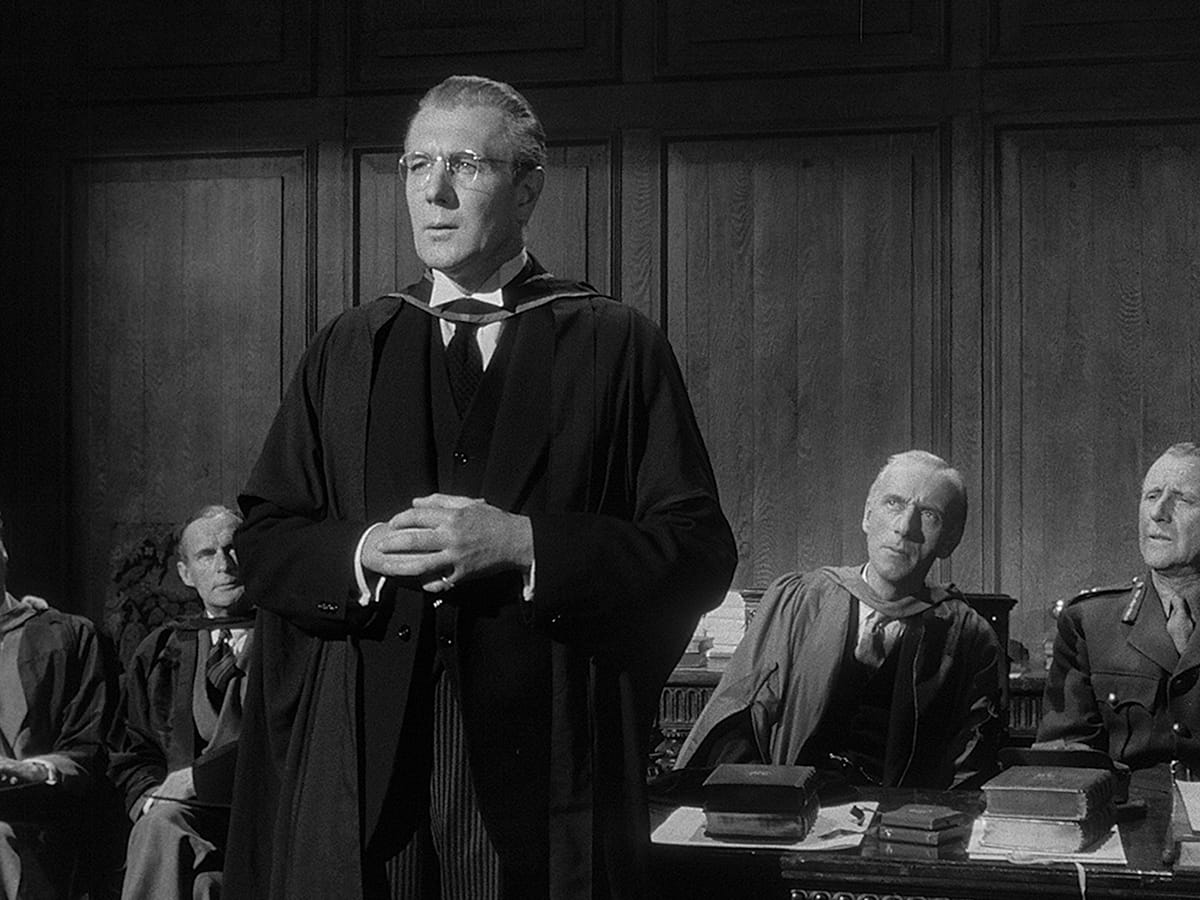

With his hair slicked back, owlish specs, a stiffly formal manner, and a high-pitched warble to his voice, Michael Redgrave plays Crocker-Harris beautifully, conveying both his utter weariness and his self-loathing. Unable to inspire his pupils, he browbeats and bullies them instead. His unhappiness is compounded by a wretched marriage to a wife who openly cheats on him (Jean Kent) and by his nagging sense that he has thrown his gifts away. As a young man, we learn, Crocker-Harris was a brilliant classical scholar. He had entered teaching with a sense of passion and idealism, both long since dissipated.

In his own person, Asquith was nothing like the Crock. A tiny but effervescent man who always wore a blue boilersuit on set, he was cultured and courteous, with a notably dry sense of humor. “Everybody adored Puffin. He was the most enchanting man,” Otto Plaschke, one of his old collaborators, said of him. As president of the UK film industry trade union, the Association of Cinematograph Television & Allied Technicians, he was one of the most influential public figures in British cinema for more than thirty years. Nonetheless, some of the same sense of failure clung to him as to Crocker-Harris. His father, Herbert Asquith, had been prime minister. His mother, Margot Asquith, was a beauty and celebrated society hostess. For somebody from such a lofty background, being a jobbing director in the British film industry hardly constituted success. His drinking problem was well publicized. There were accounts of his falling asleep in his soup or becoming so inebriated that he couldn’t walk. By the time he made The Browning Version, he must have been stung that critics who once ranked him alongside Hitchcock had begun to regard him as a mediocrity. Unfairly, they saw his self-effacing directorial style as evidence that he had no vision of his own, but was simply a conduit for the writers whose work he was bringing to the screen. What they often failed to recognize was his sheer craftsmanship. Watch a bad screen adaptation of a well-known play today—for instance, Oliver Parker’s clunky and fussy The Importance of Being Earnest—and you’ll realize instantly just how much guile and subtlety went into Asquith’s work.

For him, The Browning Version clearly had an intensely personal resonance. If Crocker-Harris had to hide his feelings, so did Asquith. As family friend Jonathan Cecil attested, “He was a repressed homosexual and he had a difficult relationship with his mother, Margot, who was very overpossessive.” But whatever insights the film gives us into its director’s troubled psyche, The Browning Version is also a coruscating study of an unhappy marriage. Imagine August Strindberg or Edward Albee relocated to the genteel home-counties England of the early 1950s and you’ll come close to its essence. Crocker-Harris’s wife, Millicent, goads him relentlessly about his unpopularity, lack of money, and failure to secure a pension from the school. Their sex life is clearly nonexistent. “I may have been a very brilliant scholar, but I was woefully ignorant of the facts of life,” he admits of the early days of their relationship.

On a superficial level, Crocker-Harris is an Englishman in the same mold as Robert Donat’s Mr. Chipping, in Sam Wood’s MGM-made Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939). There, too, a shy and repressed schoolmaster endures a rough ride at an English public school. The difference is that Goodbye, Mr. Chips soon turns into an uplifting tearjerker. Chipping blossoms thanks to his beautiful, outgoing wife (Greer Garson). Despite her untimely death, he perseveres in the classroom, teaching generation after generation of blue bloods and becoming immensely popular in the process. Crocker-Harris has no such redemption. What Asquith and Rattigan allow him (in a slight variation on the original play) is self-knowledge. He makes a speech at the end of the term in which he admits his failures and apologizes to the boys. They at last take pity on him, giving him an even more rousing reception than they do a fellow teacher who has been chosen to play cricket for England. On one level, the film is a companion piece to Asquith’s great wartime propaganda picture, The Way to the Stars (1945), which likewise probed the emotions of seemingly reserved and quietly spoken Royal Air Force men.

There is a certain reverse snobbery at work in much of the critical writing about Asquith. David Thomson has accused him of making “addled movies that accepted a 1920s notion of the intrinsic appeal of wealthy and successful people.” Raymond Durgnat was equally dismissive, coming up with the word “Rattigasquith” to attack what he felt were middlebrow stage adaptations. Such critics seem blind to the emotional intensity of Asquith’s best work. The Browning Version is so affecting precisely because it is so restrained. When Crocker-Harris does show his feelings—for instance, when he bursts into tears on receiving a gift from a pupil of a secondhand copy of Robert Browning’s version of Agamemnon—the impact is devastating.

Perhaps Asquith’s greatest achievement in The Browning Version was to coax such a searing performance out of his lead actor. Redgrave held film acting in very low regard, but on this occasion we’re in no doubt that he is utterly committed to his role. There is no false sentimentality about his playing. He shows us exactly why his character is so hated and feared by his students. Nonetheless, when Crocker-Harris is finally able to confront his own shortcomings and acknowledge his “utter failure” in his chosen profession, there is a catharsis as powerful in its own way as any found in the Greek tragedies that he so admires.

It is a measure of Asquith’s versatility that he followed his gloom-ridden account of Crocker-Harris’s fall from grace with his superbly witty and brittle adaptation of The Importance of Being Earnest, made the following year. Admittedly, one or two of the big-budget, celebrity-saturated melodramas that he directed toward the end of his career (The VIPs, The Yellow Rolls Royce) were bloated, self-indulgent affairs, but that surely should not blind anyone to the merits of his best work. The Browning Version is vintage Asquith: slow burning, understated, but with an emotional intensity that the repressive English public school setting only serves to intensify.