RELATED ARTICLE

An Education: Charles Burnett on the UCLA Years

By Andrew Chan

I’m Still Here: A Conversation with Agnès Varda

The Criterion Collection

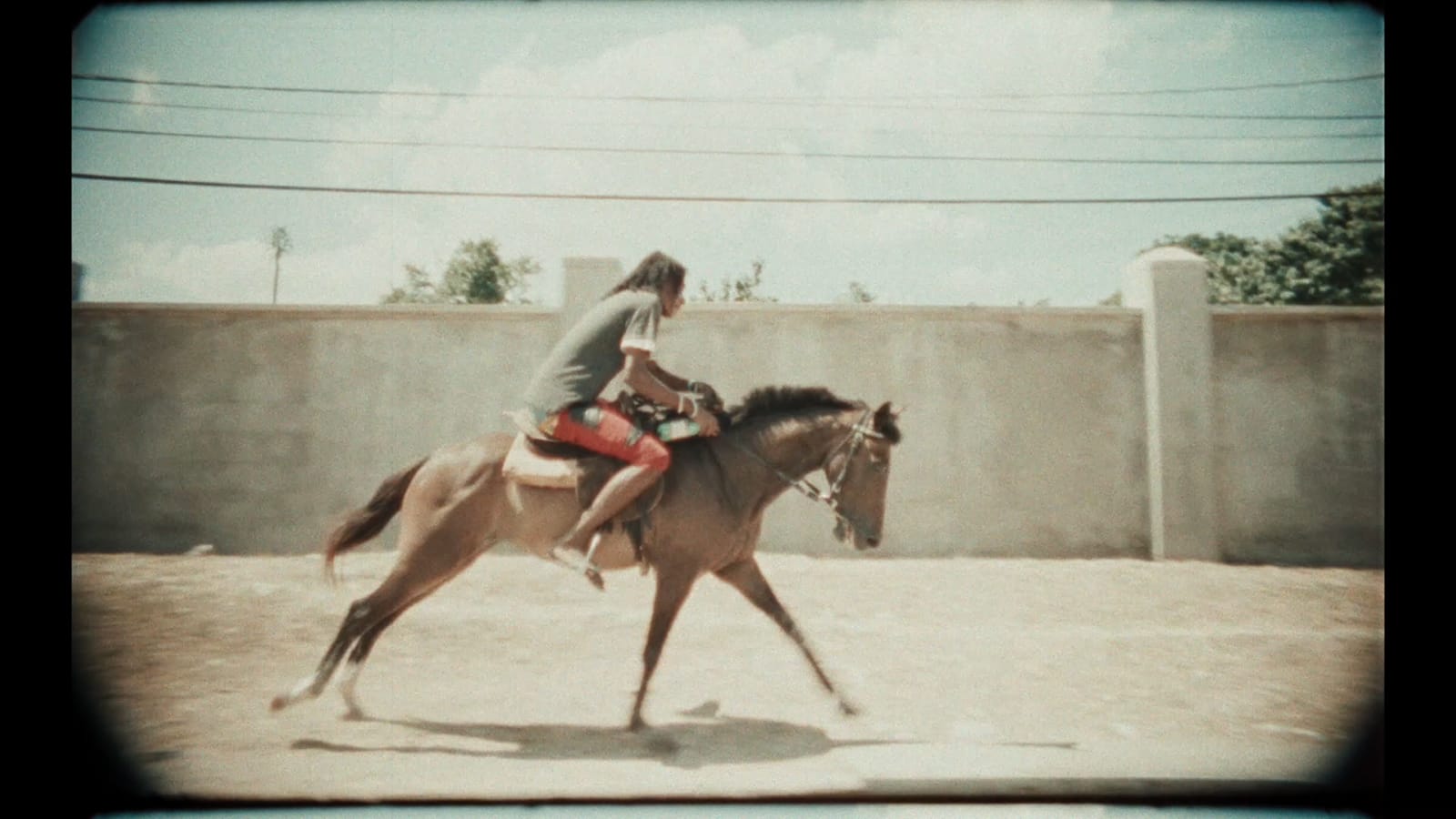

It doesn’t take more than a few minutes of watching a Khalik Allah film to intuit that he’s a photographer. Over the course of just two documentary features, the thirty-four-year-old, New York–bred artist has developed an instantly recognizable style at odds with much of American nonfiction filmmaking—one that invests a great deal of faith in the capacity of a single shot, untethered from discernable chronologies or narrative arcs, to capture spiritual truths. Reaching beyond social-realist conventions, Allah brings an audacious lyricism to his portraits of people of color who live under extreme conditions of marginalization. His 2015 breakthrough film, Field Niggas, is a highly stylized chronicle of homelessness, substance abuse, and violence on one Harlem street corner. The just-released Black Mother, one of the stand-out selections at last year’s New Directors/New Films, is a poetic travelogue of Jamaica that blends images of poverty with rhapsodic meditations on the island’s natural beauty and cultural vibrancy.

The suffering that Allah depicts is unsettling, but his films arrive at their social commentary through an

intimate, often tender approach to portraiture free of editorializing. The

people in these films carry their stories in their eyes, in their postures, and

on their unforgettable faces, and Allah, who calls his work “camera ministry,”

has a way of accessing the inner lives of even the most emotionally closed-off

subjects by engaging with the physical realities of their experiences.

When Allah began winning acclaim on the international

film-festival circuit a few years ago, his sensibilities already seemed fully

formed. But his path to cinema has been a circuitous one. As documented in his

powerful book Souls Against the Concrete,

he honed his skills in still photography, experimenting with different formats

while immersing himself in the nocturnal world that would become the setting of

Field Niggas. But the desire to

capture bodies in motion, as well as the oral testimonies of the people he befriended

on the streets, led him to merge his photographic style with the moving image.

During a visit to Criterion, he talked with us about how he arrived at his

calling and the twin influences of hip-hop and international art-house cinema.

How did you get your hands on your first camera?

When I was young, I always wanted one. Some kids want a bike or a skateboard, but for me, I was just really impressed with the fact that you could record things and have them forever on video. I was begging my mother since I was thirteen, and then when I turned fourteen, she got me a Canon ES190. At that age, I was into break-dancing and skateboarding and did some graffiti, so I was basically shooting those things. And just my friends, smoking weed. But I never edited any of it. About five years later, when I was in community college and took a course called Intro to Digital Filmmaking, I learned I could do something more with this kind of footage. Before I had just been doing in-camera edits, but that class opened my mind to the fact that I could put it all into Final Cut Pro and chop it up. Some of that stuff ended up in Black Mother, because I had been filming in Jamaica in those early years. About ten percent of the film is made up of that old footage.

Tell me what it was like spending so much time in Jamaica when you were a kid. How were those experiences different from your time there recently, while you were making Black Mother?

I grew up in Long Island, but my maternal family is from Jamaica and my dad’s family is Iranian. I don’t know the Iranian side too well, but from the age of three I was going to Jamaica a lot to see family. I’m a dual Jamaican-American citizen, so it wasn’t as if I was going as a tourist; I was seeing my aunts and uncles, and staying at my grandfather’s house. We’d all sit in the kitchen and cook up a big meal. Going to Jamaica with my family felt very safe, and they lived in the countryside, so I was experiencing a cleaner, quieter side of Jamaica.

But when I made this film, I wanted to include the struggles of the city, where you have sex workers and hustlers and gritty elements. One of the concepts of this project was to include my family within a more 360-degree perspective: the positive, the negative, the neutral. When I was a kid going to stay with my grandfather, we’d go to the monastery, and he’d just be praying over me. But I knew there was so much more to the island because I saw it just by looking out the window—people were struggling.

Stills from Black Mother