Twenty-Four Eyes: Growing Pains

One of the most awarded films in Japanese history, Twenty-Four Eyes was already a nostalgia piece when Keisuke Kinoshita directed it in 1954. For a Japanese audience just three years out of the Allied occupation following the heartrending devastation of World War II, this quietly moving story, based on a book by Sakae Tsuboi and spanning two decades in the lives of an island schoolteacher and her first twelve elementary school pupils, was seen as a celebration of the positive family values and scenic beauty that defeat and privation could not destroy. After years of propaganda and stifling censorship, it was rejuvenating for viewers to watch innocent children play, laugh, sing, cry, and grow up through the eyes of a fresh-faced, smart, and affectionate young teacher, played by the beautiful and indomitable Hideko Takamine. Twenty-Four Eyes was undoubtedly a woman’s film, honoring the endurance and self-sacrifice of mothers and daughters trying to preserve their families, and providing a cathartic cry, or “three-handkerchief” moviegoing experience. It lives on, however, not as a melodramatic tearjerker but as a meticulously detailed portrait of what are perceived as the best qualities in the Japanese character: humility, perseverance, honesty, love of children, love of nature, and love of peace.

Kinoshita, a classic case of a movie-crazy kid who ran away from home to get into the business, had already been making films for over a decade, following a long internship as a cinematographer, when he took up Tsuboi’s book. Master of many genres, he and his team had since the war made a number of hugely successful tragedies, love stories, and period films, as well as a pair of zany comedies starring Takamine as “Carmen,” an artiste stripper with country roots. What Kinoshita had not been good at, in the eyes of the wartime military government, was promoting the army suicide corps (the kamikazes). In his first films, he couldn’t help showing mothers who were distraught instead of proud that their sons were going off to die for their country, as in 1944’s Army. In the new freedom of the postwar era, the best-selling book Twenty-Four Eyes gave Kinoshita the screenwriter ample material to come out in the open with his pro-family, antiwar views; by this time he was an established director, and Shochiku Company would acquire the rights he wanted. Watching Twenty-Four Eyes, everyone could empathize and openly acknowledge the pain they had suffered silently through the war, and with Takamine’s Miss Oishi they could rejoice in having survived to reunite with loved ones.

Instead of wallowing in the rubble of the population and industrial centers of Japan, Kinoshita takes his down-to-earth, day-to-day story to the lovely Shodoshima, the second-largest island in Japan’s Inland Sea. The picturesque rural landscape has been virtually untouched by the bombs and airplanes of World War II, and we see nothing but farmers and their animals, quarry workers with their hammers, and fishermen with their nets and boats. Kinoshita’s cinematographer, brother-in-law Hiroyuki Kusuda, employs diagonals, light-dark contrasts, gentle tracking shots, and long setups with expressive close-ups to show the people in perfect harmony with their idyllic mountains, fields, and shorelines. The editing, which mirrors the sequence of the actual filming, has a natural flow—Kinoshita and his generation conceived and executed every shot in order, so the rough cut was done as the image entered the camera.

For the Western viewer, Kinoshita’s choice of music may raise an eyebrow. But if the themes of “Annie Laurie,” “Auld Lang Syne,” and “What a Friend We Have in Jesus,” played on guitar, flute, violin, and harp, seem un-Japanese, it is our ears that are a little off. It’s necessary to detach ourselves from the cultural associations we impose on music. The Western tunes and Western instrumentation are just as ordinary to the Japanese ear as the old Japanese folk songs the twelve children sing with their teacher. The easy transitions the composer, Kinoshita’s brother Chuji, makes between East and West are no more unusual than the use of Ravel and Beethoven in Akira Kurosawa’s film music. To use classical Japanese instrumentation as background in a contemporary drama, i.e., a nonsamurai film, would sound far more artificial than adapting international standards.

The story employs a favorite device of Japanese popular drama: people aging on-screen before our very eyes—from young adulthood to old age for Miss Oishi, and from childhood to maturity for her students. She arrives at the tiny village school in April 1928, and although she comes from just across the bay, she shocks everyone with her modernity, commuting on a bicycle and wearing a suit instead of a kimono. Talking to her mother about the villagers’ unfriendliness, she reveals that it is not an air of superiority that motivates her: she lives nine miles away, too far to walk, and since it’s impossible to ride a bicycle in the constricting drapery of a kimono, she has recut and sewn an old kimono into a suit. She retains this apologetic and humble demeanor always, even when criticized in front of her students.

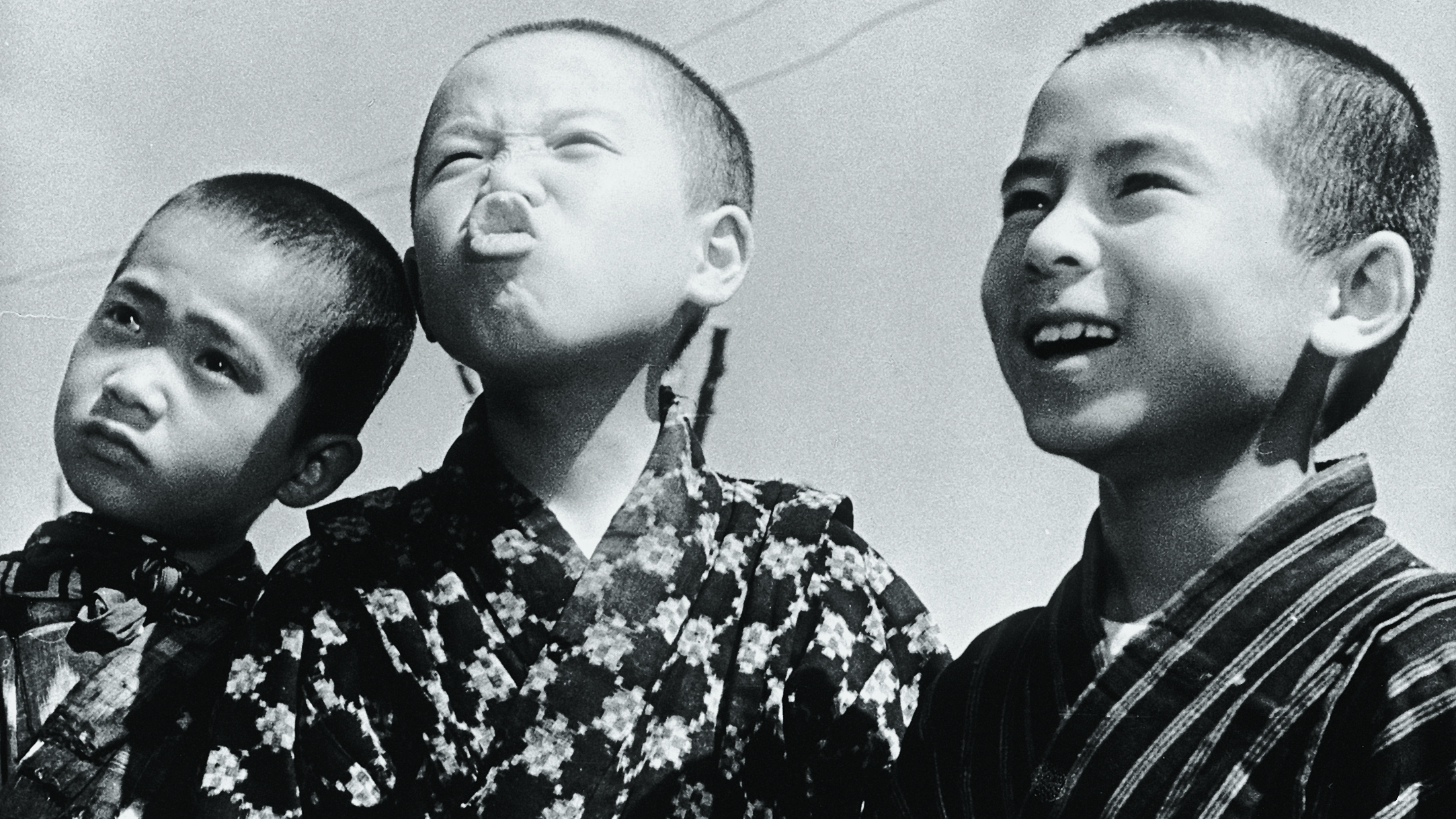

Kinoshita builds Miss Oishi’s relationship with her students not through classroom drudgery but through outdoor excursions, song, and playfulness. One incident causes such severe injury to Miss Oishi that she has to give up her bicycle and her distant job. Her students, bored at the hands of their new, unmusical male teacher (Chishu Ryu), long for her so much that they set out without food or water to find her. Miss Oishi rescues them from a bus on her way home from a doctor visit, and her mother serves them a huge meal of noodles at their home. The next day, packages of rice, beans, dried fish, and other staples arrive at Miss Oishi’s home from the parents of the rescued pupils. On crutches, the teacher impulsively travels to the village to thank each family in person. Kinoshita treats this display of traditional Japanese politeness and humility with gentle humor, as Miss Oishi mixes up people’s gifts and some confess they gave nothing at all. Her acceptance in the village is thus achieved through the love the children give back to her.

The story progresses at a leisurely pace, accompanied by Chuji Kinoshita’s lilting score, Kusuda’s reverent cinematography, with no incidents of great drama or peculiarity. Five years pass while Miss Oishi teaches at the big school closer to her home, and when she gets married to a boat captain, her former students come to check out the bridegroom. The Japanese invasion of China and the Great Depression ensue without much affecting the simple lives of the islanders. Only the songs change, to sadder classics reflecting on the loss of comrades in battle.

The war reaches the little island. More and more boys are drafted and come back only in processions of ashes carried in white, cloth-bound containers by their grieving mothers (the Japanese draft age went down to fourteen near the end of the war). Meanwhile, Miss Oishi sees a colleague arrested as a Red for a book of essays he has used in class. Shocked, she confesses that she too has been using it. The principal urges her to be careful and above all to say nothing against the war. Eventually she leaves teaching because she can’t make herself encourage boys to become soldiers, and she’s labeled a coward even by her own elder son. In the course of the war, she will lose her mother, her husband will be killed at the front, and her little daughter will die in an accident. When August 1945 comes and the emperor speaks to the nation over the radio for the first time to announce the surrender, she seems to be alone in rejoicing that no one else will die because of the war.

The resonance of Twenty-Four Eyes for audiences then and now is that Miss Oishi speaks for countless people the world over who never want to see another father, son, or brother die in a war for reasons they do not understand. Kinoshita’s antiwar message is aimed more directly at Japan than the films of an Ozu, whose war-widow daughter-in-law in Tokyo Story calls herself selfish for not thinking about her dead husband every minute, or a Kurosawa, whose major antiwar film of the period, I Live in Fear, focuses on the United States’ use of the atomic bomb. Even Mikio Naruse’s 1955 Kinema Junpo and Mainichi Film Concours best film winner Floating Clouds shows the Pacific War and its aftermath more in terms of individuals exploiting each other than as a governmental policy that hurts the country’s own people. The isolation and chronic poverty of the Shodoshima community portrayed in Twenty-Four Eyes bring this point home with all the more vehemence. When Miss Oishi tells boys who were her students that she likes ordinary shopkeepers or farmers better than the higher-status military men, it is her way of saying she prefers life over death. Her sentimental tears as an older woman finding the children of her past students in her classroom when she returns to teaching after the war are totally justified, for here is innocent young life again.

Kinoshita presents a teacher of the type every child would cherish, because she cherishes her students. She looks at the whole child, takes into account his or her home situation, consoles, advises, encourages, and nurtures. She accepts the criticism of parents and administrators without complaint, but she never abandons the child. Her treasuring of these relationships is an expression of the kind of person Kinoshita himself was in the world of Japanese cinema. After Twenty-Four Eyes, Kinoshita would continue to turn out two, and sometimes three, films a year for two more decades. He enjoyed celebrating the fortitude and optimism of Japanese women in particular, and in such films as The Ballad of Narayama (1958) and The River Fuefuki (1960) he experimented with color, genre, music, and classical stage effects. He retained his criticism of authoritarianism and hypocrisy, whether it was of governments exploiting their people or parents stifling their daughters (1964’s The Scent of Incense). His crew became his family, and he cherished those with whom he worked—to the point where he was the go-between for the offscreen marriage of his assistant, Zenzo Matsuyama, to his versatile frequent leading lady Takamine. Grace and playfulness imbued his work and his manners. Of all the film directors I have interviewed the world over, he is the only one who ever sent me a dozen red roses as a thank-you.