Impure Cinema: A Conversation with Arnaud Desplechin

A sense of cacophonous emotion and manic fervor tends to permeate the works of Arnaud Desplechin. But when I sat down with him at the Film Society of Lincoln Center back in October, on the morning after the New York Film Festival premiere of his new tour de force My Golden Days (which has its theatrical premiere today), the French director was soft-spoken and collected. Desplechin’s new film is the prequel to his masterful 1996 movie My Sex Life . . . or How I Got Into an Argument—and as such, it invites viewers to reflect on the past two decades of his career, during which he has brought to life a set of richly intricate and emotionally potent tales that evoke the singular pleasure of cinema, from My Sex Life and Kings & Queen to A Christmas Tale and now My Golden Days.

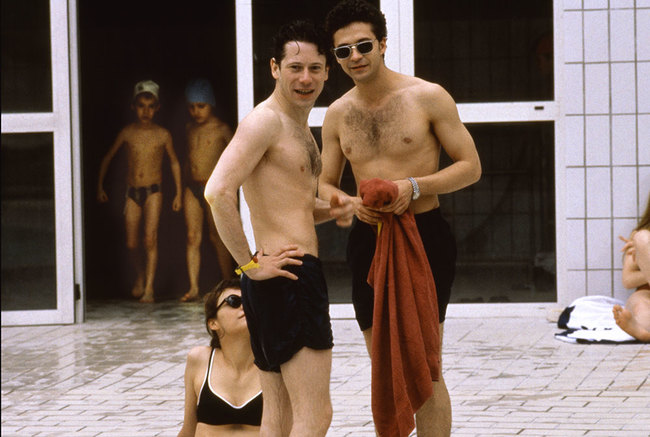

In My Golden Days, Mathieu Amalric reprises his role as the romantically hapless intellectual Paul Dédalus, now a middle-aged professor reliving the memories of his 1980s youth and the lost love that still haunts him. Amalric’s reminiscence unfolds over three chapters of Dédalus’s early years—from a harrowing childhood in Roubaix and a consequential teenage misadventure in the USSR to the solitude of his university years and his introduction to Esther, with whom he begins a troubled romance. Quentin Dolmaire and Lou Roy-Lecollinet deliver stunning performances as the young lovers, whose relationship we observe develop and ultimately disintegrate.

I spoke with Desplechin about revisiting the world of his breakthrough feature, his desire to communicate with a younger generation, and his signature cinematic flourishes. Desplechin is back in New York amid a retrospective of his work at the Film Society, where he will participate in Q&As following screenings tonight and tomorrow of My Golden Days.

There are so many of them! Before I saw Fanny and Alexander, I was a technician and I loved being a technician, but after seeing that, I was a director. The film just changed my life. I also remember my gratitude when I saw Moonrise Kingdom; I’m positive that’s when I started to write My Golden Days. To see Wes Anderson working with these two inexperienced actors mixed with big movie stars in a film that’s so simple and so humble and so complicated at the same time, I wasn’t jealous of it because I love him, but I thought he was so lucky, because he found a way to speak with someone from another generation. So then I had to find my way to do that and have an artistic dialogue with very young actors.

Your films have always portrayed characters at pivotal emotional moments in their lives—whether that’s the postcollegiate existential crisis of My Sex Life or the familial unraveling of A Christmas Tale. Have you always wanted to make a more youthful, coming-of-age film as well?

It came later in my life. I made a film with movie stars—Benicio Del Toro and Mathieu Amalric [Jimmy P.]—and after that I made a small film for French television where I was working with very skillful, experienced French theater actors that could do anything [La forêt]. And I thought, “Yeah, but if my writing can’t be useful to a young girl or boy, it’s useless.” I know that I’m not able to improvise, I can’t steal young people’s way of speaking—I’m not Larry Clark! I love Larry Clark, but I’m not him. What I can do is write these quite elaborate lines that are funny, strange, and complicated, but they can’t only be useful for professional actors, they have to be useful for a new generation to take my words and make them their own and speak about themselves through my writing. So that was the goal, and that’s what I discovered with Moonrise Kingdom.

My Sex Life starts with a narrator saying that Paul and Esther have been together for more than ten years and they haven’t gotten along for more than ten years. I had this remorse, thinking, how did this happen that they did once get along? How was the story at the very beginning? She’s a girl in this small town and he’s this guy who already lives in Paris, who is a scholar and so serious, and she’s so brash and aggressive and full of life. In a way, the heartbreaking thing is that it’s a perfect match; Paul without Esther would be nothing. But on the other hand, they don’t match because they belong to two different worlds, so that could be a definition of love. To date someone who comes from the same world, it’s boring; it’s too easy. So a few years after My Sex Life, I thought it could be really interesting to see the two of them in a museum looking at paintings and he’s describing the face of this girl and that would be their first meeting and show why they’re a perfect match and why they don’t match at all.

I asked them not to look at My Sex Life. But after that they cheated and watched it. Quentin Dolmaire asked me if he should meet Mathieu to catch some of his mannerisms, and I told him no. I told him I wanted him to invent his own Paul, to speak with his own voice, and that I didn’t want him to impersonate anything. When they saw the film, Mathieu was struck, and said, “We have the same way of speaking!” And I remember Quentin said, “Yes, this is Arnaud’s way of speaking.” I said, “Wrong! Because actually when I’m acting in front of you to give you the right note, I’m imitating Mathieu.” So we didn’t know who was imitating whom exactly, but we were just sharing Paul’s character.

The first scene with Paul and Esther outside the school, when she’s sitting at the base of the statue, she’s just like a statue herself, she has no weakness. She’s a pure block of existence, nothing can move her, and she’s in front of Paul who is so vulnerable. She has boyfriends, but love never happened to her. She thinks, “I could be a heroine, I could be a queen, I could be something larger—if love happens to me, I will be the most important lover on earth.” And because Paul doesn’t have a phone and she has to write to him, she becomes the writer of herself. She becomes the novelist of her own tragedy. But, oddly enough, love happened to her and she suddenly discovered that she had a price to pay to become a heroine, and it was to become vulnerable and human. She’s surprised because she doesn’t know how to defend herself any longer; she wasn’t breakable and now she is, and that makes her a heroine and it’s tragic.

There are a number of recurring flourishes in your films that give them a fairy-tale-like quality, even when they’re rooted in the most genuine drama: for instance, your affection for iris shots and zooms, and the way you alter the tone of a scene with music. How do you approach these technical aspects to further the narrative you’re trying to tell?

It’s playful, but it belongs to cinema. I love the tools of cinema, but each time I have to have a good reason for using them. It has to be fair to the storytelling and the performances, and not just add tricks, but try to tell you what I want to tell you and be faithful and respectful to the performances. I love to do zooms, but when I was nineteen years old I thought bad things about them. I thought they were gross and that tracking was better. But then I discovered Fanny and Alexander, and that was zooming all the time. I thought, that’s great, let’s be impure. But when you are close, when you are zooming on the face, sometimes it’s too much for the performance. Sometimes you also just need to be shy and you want to say something very precise to the audience.

Yes, on several levels. The cowriter, Julie Peyr, said to me, “Arnaud, you’re really back on your tracks, because the first part of the film is, in a way, La vie des morts, and then the spy section is La sentinelle, and the third is obviously My Sex Life. So you’re quoting yourself.” So I had to be fair and say, I’m revisiting these tracks, but the thing that was so exciting was the possibility of a dialogue with a new generation. That’s why it was not obscene to go back to these movies, but to now visit them with sixteen-, seventeen-year-old actors and try to find a common language together. So I brought my old, dusty material to a new generation and had them make it their own.

Did you watch parts of those movies to reanimate them in your memory?

I never watch my films because I can’t fix them any longer, so it’s useless.

To me, realism is an ideology. I don’t think realism makes films more true. Wes Anderson is depicting a world of dreams, but he’s saying the truth at the same time, and his films belong to genre. You can see the truth in a western, noir, or any kind of genre. So to me, when I’m looking at a realistic movie, I’m looking at the codes as if it was a western. In a realistic movie poor people are nice and rich people are bastards—it’s a code. In life, that’s not true. When you’re poor, and believe me I have been poor, you’re not nice. You’re dumb, and you’re angry, and you have to survive. So I love realistic movies, but just as a genre. That’s my way of looking at films. My love for cinema comes from the idea that it’s the only art where there is no difference between what is noble and what is popular. So that’s why I fell in love with cinema when I was seven or eight—because I could see adults discussing films, but I knew that films belonged to me, because films belonged to kids—and that’s the beauty of it, this lack of difference between what is noble and what is ignoble.