A Conversation with Richard Shepherd

It was Jules Stein, head and founder of MCA, who plucked Richard Shepherd out of Stanford and made him into a real New York agent of the fifties, a gentleman agent, the kind we look back on today with nostalgic reverence. You’d know without knowing that Shepherd, with his handkerchief and tie always in sync, was Ivy League all the way; he was a well-groomed journalism major, genteel in taste and manner, and according to his professors, the best art forger the faculty had ever seen. Shepherd could do Chagall like Jonathan Winters did Burt Lancaster—and it got him a little work, until someone told him he had to make a living.

Then it was Jules Stein and MCA. In time, Shepherd amassed a spectacular client roster that included Henry Fonda, Marilyn Monroe, Grace Kelly, and several dozen immaculate others. But the corner office wasn’t enough. Shepherd wanted to produce. He announced his intentions to Lew Wasserman (“Good luck” was the only reply) and moved out to Los Angeles, where he teamed with Martin Jurow, one of the industry’s top entertainment lawyers. Together, they formed Jurow-Shepherd Productions and started looking for material. The Hanging Tree (1959), a western with Gary Cooper and Maria Schell, was their first picture. The Fugitive Kind (1959) was their second.

I met Shepherd at his home in Bel Air on March 22, 2010. We had talked many times before, but never about The Fugitive Kind.

Sam Wasson: Marty Jurow, in his book Marty Jurow Seein’ Stars, says the idea to film Tennessee Williams’s play Orpheus Descending originated with Anna Magnani. Before you and he started Jurow-Shepherd, Magnani was his client at William Morris, and after the success of The Rose Tattoo, she wanted to return to Williams. How do you remember the beginning of The Fugitive Kind?

Richard Shepherd: Marty and I knew the play because we were both from New York and had seen it onstage with Maureen [Stapleton] and Cliff Robertson, who had played the leads. Presumably, Marty’s recollection is correct, but Anna Magnani and I didn’t have a relationship, so I can’t speak to that. Before the film, I didn’t know her at all. What I can tell you is that I brought Joanne Woodward aboard—she was a client of mine—and Marlon and I were good friends. But you know, before Marty and I got started on the project, [producer] Sam Spiegel wanted to do Orpheus Descending.

SW: He wanted Ingrid Bergman.

RS: But Tennessee didn’t want her! That I could never understand. If you had a choice between Anna Magnani—a great actress, but you can’t understand a damn thing she’s saying—and Ingrid Bergman . . . I mean, come on! It’s night and day! But that’s how we got to make The Fugitive Kind, because we would do it with Magnani, and that’s who Tennessee wanted.

SW:The Fugitive Kind was sexually audacious and had a highbrow literary source. In other words, risky. Did Jurow-Shepherd have a reputation for trying difficult material?

RS: We both had backgrounds in New York and were very involved with artists that ended up working in the theater, and many of them, clients that Marty and I looked after, from Monty Clift to Carroll Baker to Marlon, were all of that certain type. Kazan, Williams, Arthur Miller, these were the guys then. So no, we never thought of ourselves as going for difficult material, it was just the hand we were dealt, I guess. But we were cognizant of trying to make the stuff accessible.

SW: Is that why you changed the title from Orpheus Descending to The Fugitive Kind?

RS: I think so. I think we thought it was too intellectual. It wasn’t a big hit play anyway, so why not change it? The title Orpheus Descending had little recognition; it wasn’t doing us any favors. So we went with The Fugitive Kind. That title, I think, came from Meade Roberts, who adapted the screenplay with Tennessee. We were throwing a lot of possibilities around. Some of the others we had were Stranger in a Snakeskin Jacket, Life’s Companion, Burn Down a Woman, and Burn a Woman Down.

SW: Tennessee gets shared credit with Roberts, but how involved was he in the adaptation?

RS: Other than a couple times when Tennessee would come up to the location in Milton [New York], he didn’t seem to have a significant hand in the script. If we wanted changes, or if Sidney wanted changes, we talked to Meade and he did it.

SW: At first, Brando turned down the part of Val Xavier, which had been written specifically for him. What turned him off?

RS: He didn’t admire Magnani as an actress, and he also felt she was . . . Well, I should say, there’s a scene in the movie, the first scene when the two of them are together, when Marlon first goes into her shop. She’s talking to him at the bottom of the stairs, and at one point in the scene, she says to him, “Have you got any references?” and Marlon says, “Yeah, I got ’em right here” and reaches into his snakeskin jacket pocket and takes out this crumpled letter, and kind of embarrassingly unfolds it, and just took a really long time in handing it to her. Finally, once he handed it to her, Magnani did the same thing with the letter, but tripled the amount of time it took. She turned it over, smoothed it out, examined it—you know, she was just trying to outdo him! That’s the way she was as an actress. I think that’s part of the reason Brando didn’t want to be with her.

SW: And apparently she was also trying to go to bed with him.

RS: Oh, yeah. Yeah. He wasn’t interested and she was angry. They’d sort of spar, you know? I’ll tell you something else about Magnani: she would take control of everything.

SW: Let’s go back to the moment when you actually got Marlon. A lot of people think Elizabeth Taylor was the first star to be paid a million dollars for a movie, but actually it was Brando. Why is there this misconception?

RS: Because we hid it. The story basically is that Tennessee wrote the play for Marlon. He wanted him and Magnani to do it in the theater, but neither of them did. When we set up the deal with United Artists, we had Tony Franciosa [for the part of Xavier], and he was getting $75,000. Then I got a call from Jay Kanter, Marlon’s agent, who had been my roommate in New York and my best man at my wedding, and he called to say that if we still wanted Marlon he would do it, but only if he got a million dollars. He needed that much money to pay for his divorce arrangements with Anna Kashfi. And I said, “Well, I’d love to get him, but I don’t know. A million dollars? I’ll have to talk to [United Artists head] Arthur Krim.” It just so happened that Arthur Krim was in Los Angeles, and he was staying at the Beverly Hills Hotel, so I drove over to the Beverly Hills Hotel and went to see him and said, “We can have Marlon, but he’s got to be paid a million.” Krim didn’t know what to say to that. There was no actor he knew or I knew who had ever been paid a million dollars. So he said, “Well, you can do it, but you have to make up the contract in a way that says he’s not getting the million for appearing in the movie. He’ll have to get some of the money for publicity and various other things. I don’t want the contract to show Marlon got it all just for acting.”

SW: Why did Krim want to conceal it? It could be spun into a nice piece of promotion for the movie.

RS: I don’t know. I think they thought it was wrong. It was bad for the industry to have to pay an actor a million dollars. It set a precedent. So I called Jay [Kanter] and said, “We’re gonna make the deal, but we have to sort of set it up.” I can’t remember the exact wording of the contract, but Marlon only got $750,000 for his performance, and the other quarter of a million was just for whatever the clauses were. You know, we spread it out in such a way that it wasn’t to be against the twelve weeks or the ten plus two he got as an actor . . . So we went to see Tony [Franciosa] and told him that we had Brando and were now prepared to pay him $75,000 not to be in the movie. He couldn’t believe it! “Gimme the check,” he said. And that was it.

SW: Brando was editing One-Eyed Jacks in L.A. at the same time as he was making The Fugitive Kind. That couldn’t have been easy.

RS: It wasn’t. As a matter of fact, because he was flying back and forth, United Artists wasn’t happy. I remember—and this is a friend of mine we’re talking about—he flew to L.A. for the weekend and showed up on Monday hours late for the call. And in front of everybody, I said, “For a fucking million dollars, you can’t be on time?” I really yelled at him.

SW: How did Brando take that?

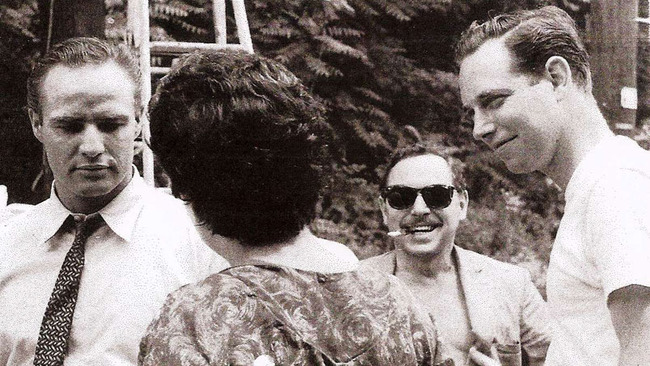

RS: He said, “You’re right.” I mean, I could yell at the guy, because we were friends. And I don’t just mean acquaintances. Marlon was one of the groomsmen at my first wedding. There were a lot of things that were difficult about him, but I remember him saying—not to me but in my presence—that it troubled him that he could never walk into a room where somebody didn’t get tense because he was around. That bothered him. The minute that that happened, he would become more pompous. I saw it happen. He just didn’t want to be put on.

SW: How influential were Kazan’s films on the production of The Fugitive Kind? Not just in terms of Brando and Williams, but looking at your crew, I see you used a lot of Kazan’s people.

RS: Once we knew that we were going to make the picture, to get Kazan’s crew together was a given. They were the best in New York. There weren’t that many films being made out there, and Kazan wasn’t working. There were [associate producer] George Justin and [assistant director] Charlie Maguire and [cinematographer] Boris Kaufman and his unit, all of them from On the Waterfront. And they all knew Sidney, who I was involved with as an agent at the beginning of his career. I made his first deal, you know, for 12 Angry Men. I represented Henry Fonda and helped get the picture made. I really produced the movie, but, you know, as an agent I couldn’t get producer credit. Anyway, I remember there was a scene that went on and on and on, and Sidney was concerned about it. He wanted to get away from the table with all the jurors, and I can remember Kazan telling Charlie Maguire what to do, and Charlie came back to Sidney with all of these ideas about how and when to move the camera, and it worked. To this day, I don’t know if Sidney knew that it was actually Kazan who told Maguire. [Laughs] I just remembered a great story about Tennessee. [Laughs] The first read-through of The Fugitive Kind was in what was like a ballroom on the second floor of some building on the east side of Broadway. There was a big, long table, and on one end was Sidney Lumet and on the other end was Marlon Brando. And on both sides was the entire cast. All around the table. All the major actors. Tennessee Williams, Marty Jurow, and I were not at the table but sitting in three chairs against the wall. Sidney, who was so nervous his hands were shaking, said, “Okay, let’s start.” So Marlon starts to read that first long monologue. You know the one? In front of the judge? And Marlon starts mumbling through it. The whole thing, just mumbles. And everyone leaned in to hear, and I could see Tennessee was getting restless. Finally, he stood up and said, “I can’t hear my fucking dialogue! I’m leaving!” And he got up and left. [Laughs] So Sidney had to go out and bring him back in.

SW: United Artists’ reputation was very good, from an artistic point of view. Did they leave you alone to make the picture you wanted to?

RS: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. They were really great in those days. It wasn’t like working for Dore Schary or Sol Siegel or Darryl Zanuck or Jack Warner. Just to give you an example: I made a western with Jack Warner, and the first thing he said to me was “Every western has to start with a map.” So that’s where you were at Warners. But no, you never saw anybody from United Artists. They weren’t a traditional studio. They made truly independent pictures. But you know, I don’t think they liked the movie.

SW: Why not?

RS: They didn’t knock themselves out marketing it. But if they had and it was a hit, it would never have become a cult movie. [Laughs] Is it a cult movie? [Laughs] It didn’t do great business, but our next picture did okay, I guess.

SW: What picture was that?

RS:Breakfast at Tiffany’s.