Jon Raymond’s Top10

Jon Raymond is an author and screenwriter living in Portland. His books include The Half-Life, Livability, Rain Dragon, Freebird, Denial, and God and Sex. He has also published a collection of art writing called The Community: Writings About Art in and Around Portland, 1997–2016. His screenwriting credits include Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff, Night Moves, First Cow, Showing Up, and the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce.

-

1

Martin Bell

Streetwise

I first saw this in the late eighties as a high school kid, at the great, holy art theater of my youth, Cinema 21. It never left me. In 1983, the photographer Mary Ellen Mark made a photo-essay for Time magazine about a group of street kids in downtown Seattle. Recognizing there was more yet to tell, she passed the subject on to her partner in art and life, Martin Bell, to document on celluloid. Armed with eighty grand from Willie Nelson (!), Bell and his crew decamped to Seattle and shot for fifty-five days, coming away with a group portrait of almost shocking lyricism and intimacy. We see kids scavenging in dumpsters, kids climbing into cars and turning tricks, kids fighting on the street, kids overall making a lot of terrible choices that will probably scar them for the rest of their lives or, put another way, enjoying a final burst of reckless exuberance before their long years of morbid addiction and shit jobs kick in. It’s no spoiler to admit that tragedy occurs. And even though it’s probably wrong to dwell too much on the aesthetics of a film like this, it has to be said: the frames are just insanely gorgeous. From the first image of fourteen-year-old Rat steaming on the piers between jumps into the cold waters of Puget Sound to a barely adolescent prostitute named Tiny primping in her alcoholic mom’s cruddy house to a hundred other fugitive moments captured in the blocks surrounding Pike Place Market, we gaze on these bleak lives through a prism of aching beauty. Yet another unfairness to go along with the rest.

-

2

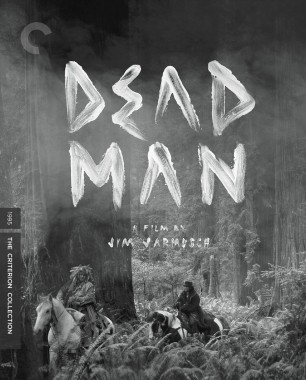

Jim Jarmusch

Dead Man

There are a lot of westerns out there, but not that many northwesterns. As a longtime Portlander, I’m always on the lookout for historical backdrops lacking big skies or tabletop mesas. For a long time, there was one big one: McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Then along came Dead Man, Jim Jarmusch’s visionary Symbolist poem of the American West that begins in the Great Basin (more or less) and ends in the ferns and moss and finally the ocean beyond the Cascades. Johnny Depp plays a callow Ohioan called William Blake (no relation) who travels cross-continent only to be injured by a bullet that lodges near his heart. He’s rescued by a man named Nobody (the great Gary Farmer), who leads him on a voyage into a landscape of increasing mystery and violence, populated by wanderers, maniacs, and hired killers, all with odd stories and quirks, most of them packing guns of various gauges. Filmed by Robby Müller in hallucinatory, Night of the Hunter–style black and white, the movie gets its soul from Neil Young. The sweet thunder of his guitar becomes a kind of lullaby inside this melancholy, hilarious, psychedelic journey into the setting sun.

-

3

Claire Denis

Beau travail

On a level I think I get this movie: a French Foreign Legion Adjudant-Chef named Galoup bears an unrequited love for his elder, more worldly Commandant, Bruno Forestier, who in turn bears a paternal kind of love for a young recruit, Gilles Sentain. The jealousy created by this triangulation leads Galoup to torment Sentain and ultimately almost kill him, a transgression for which Galoup is expelled from the Legion, his home. But how this is all expressed in the film is utterly mysterious. In shards of sky-hammered desert imagery, Claire Denis patches together shots of young men training, men eating, men walking the streets of Djibouti at night. There are shots of men swimming, young African women dancing. A few voice-over fragments orient us, barely, in the mind of Galoup, with his soldierly turpitude, and recurring shots of his acne-scarred face watching the other men create a troubled psychic ambiance. But the gaze structure is always fascinatingly complex, at once homo- and heteroerotic, male and female. Could Pasolini and Riefenstahl collaborate? Is Joseph Conrad in there somewhere? Gay Conrad? (No, it’s actually an adaptation, of sorts, of Melville’s Billy Budd.) At times, the film verges on beefcake, all the guys lounging in their Legionnaire short shorts, but the energy is overwhelmingly spiritual-sexual, as daddy love and son love and brother love and soldier love become involuted and threatening. And then, bizarrely, Neil Young turns up! Again! As the men march through a wasteland, his song “Safeway Cart” plays. Why? I don’t know! Nor do I know why the last image of this film is so revelatory, but it is. In memory or maybe in death, it seems to suggest, what was once hell becomes heaven.

-

4

Satyajit Ray

The Music Room

Let’s stick with the music thread and go with this stately tale by Satyajit Ray of a dissipated feudal lord who loves music above all else. For awhile things are okay for Biswambhar Roy. He spends his days lounging in the palace, staring out at the horizon, eating sherbet, not bothering to exploit his lands or oversee any improvements. Mostly he likes throwing lavish recitals in his music room, where he hires groovy sitar and dilruba and tanpura players to entertain his male subjects/buddies. The men sit on the carpets under the glowing chandelier and bob their heads, smoking hookahs, drinking wine, and sniffing drugs much as men have done throughout the ages. But when Roy’s son is killed in a cyclone at sea, his lordly life of indolent sensualism ends. Roy’s estate, already precarious, crumbles around him, and the precious music room goes silent. In the end, he throws one last party, draining his coffers, and although it’s a real banger, he’s thrown from a horse directly afterward and dies. I’ve never seen a character like Roy before: sad, lazy, imperious, doting. He’s a guy who loved music and his son. What else is there to love, really?

-

5

John Waters

Pink Flamingos

I first saw this film at the Castro Theater in San Francisco in the early nineties at about age twenty or twenty-one. It was a good time and place for it. I’d heard about the movie of course—someone eats dog shit!—but the whole idea of John Waters and Divine was still more like a rumor to me. The theater was sold out that night, the crowd rambunctious and a little intimidating. The movie started, and as it turned out no one there was remotely shocked. They were all laughing along with the scenes, talking back to the screen, engaged in some kind of ritual appreciation. Gradually, it began to dawn on me: these people—both in the theater and on the screen—were sophisticated beyond my comprehension. They were connoisseurs of sleaze and camp and everything, but they were also tuned to deeper frequencies, seeing something underneath the images that went beyond mere exploitation or transgression, beyond even mercy or forgiveness, and into something like maniacal acceptance and monstrous empathy. John Waters would probably hate to hear this, but I felt like something almost saintly was going on. I walked out of that screening a disciple for life.

-

6

Mike Leigh

Topsy-Turvy

Is there a better depiction of the joys of artistic collaboration than Topsy-Turvy? In this well-appointed double artist biopic, Mike Leigh doesn’t waste time on fake dramatics or boring tropes about tortured genius or fickle muses. We meet Gilbert and Sullivan at an impasse in their creative partnership, seeking a way forward that’s not merely repetition or weird departure. Doubts are aired. Personalities chafe. That’s drama enough! When Jim Broadbent captures the first flicker of his next idea at a Japanese arts-and-crafts exhibition, it’s thrilling, almost like having the idea yourself. From there, we get the luxurious pleasure of watching a group of incredibly talented people (Shirley Henderson: fantastic) engaged in the best, most absorbing labor in the world, using their imaginations to make something beautiful.

-

7

Charles Burnett

Killer of Sheep

As with Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles—another fragile realist masterpiece set in hardscrabble Los Angeles that also happened to fulfill a thesis requirement—the fact that Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep even exists is amazing. The fact it’s amazing is even more amazing. Shot over multiple years with almost no resources, beset by music-clearance problems, the movie follows a loose, lyrical pattern as it keeps an eye on Stan, a guy who works in a slaughterhouse in Watts. We get moments with his family, moments at the store. Kids and neighbors drift through, sometimes drawing our attention to their own lives. One of the larger episodes involves going to pick up a used engine and trying to drive it home in a truck. Stan’s life is mostly built of dead ends, but the gravity and texture of his world is always poignant, if not piercingly lovely. As with the characters it depicts, the movie’s odds are stacked against it, but the poetry is indomitable.

-

8

Alan J. Pakula

The Parallax View

Alan Pakula’s Paranoia Trilogy—Klute, All the President’s Men, and The Parallax View—springs from that rattled moment in American life when our entire nation turned into conspiracy theorists. And like the conspiracies our nation spawned, the movie itself is maybe a little derivative and half-baked while never becoming uncompelling or even entirely untrue. Warren Beatty plays a journalist who uncovers a corporation recruiting Oswald-like sociopaths to commit political assassinations. What’s the corporation’s political agenda, exactly? Hard to say. Are there really that many assassinations necessary? And then who assassinates all the witnesses, as keeps happening in the movie? Certain critical thinking remains unfinished. But for me, the big pleasure of The Parallax View—and the other films in the trilogy, too—is less the political insights they offer than the long lenses and natural light. Gordon Willis shot all of them, and in The Parallax View he captures the watery grain and hard slant of the Pacific Northwest sun with delicacy and grace. There’s a lot of negative space to let everything breathe, and the graphic elements of the compositions are arranged with great daring and precision. It turns out 1974 was a moment of creeping paranoia and also excellent film stock.

-

9

Amy Heckerling

Fast Times at Ridgemont High

When this movie came out in the early eighties I remember thinking it was vulgar in the manner of Van Halen, Motley Crüe, and skateboarding. I guess I was kind of a prig as a kid. And while I never did come around to skateboarding, on the question of Fast Times I can admit now that I was wrong. It isn’t vulgar at all. It’s sweet. It’s about a group of young, humanly scaled characters groping through humanly sized situations, like having sex in pool houses and throwing their Long John Silver costumes out the car window. When Judge Reinhold picks up his sister, Jennifer Jason Leigh, after her secret abortion, meeting her outside the clinic with a mixture of exasperation, concern, and ultimate loyalty, that’s exactly how it would be. And the fact that her boyfriend failed to drive her doesn’t make him bad, exactly, it just makes him . . . himself. Compared to the steroidal garbage churned out by the culture industry these days, Fast Times is practically Chekhov.

-

10

Nuri Bilge Ceylan

About Dry Grasses

I saw this just a few weeks ago. At first I thought it was going to be a detailed procedural about a rural schoolteacher accused of inappropriate behavior and ultimately getting devoured by a grim state bureaucracy. But it turned out that was only the preamble. The disciplinary episode at the beginning launches us on what instead becomes a portrait of Samet, the rural schoolteacher in question, as he grapples with his own misanthropy and thwarted dreams against the bleak, mountainous landscape of eastern Anatolia. A love triangle emerges, a lot of conversation goes down, a betrayal occurs, all within the dense visual weave and fuzzy moral parameters of actual lived life. The characters have ideals, but do they believe in their ideals? Is Samet merely an asshole? In the end, yes, he is, but so much more than that. Spending time with these characters didn’t feel like watching a movie, it felt like living.