Davy Chou’s Top10

Born in 1983 and based in Paris and Phnom Penh, Davy Chou is a French Cambodian director and producer. He cofounded the French production company Vycky Films and the Cambodian production company Anti-Archive. His first feature, Diamond Island, was awarded the SACD Prize at Critics’ Week at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival. His second feature, Return to Seoul, was selected for the Un Certain Regard lineup at Cannes 2022 and shortlisted for an Academy Award for Best International Feature Film.

-

1

The Koker Trilogy

When I watch a film by Kiarostami, I think: this is the definition of cinema at its best. He’s a master, and The Koker Trilogy contains elements that can be found in all his cinema, including the innocence of childhood as a moral lesson for adults, the road movie and the possibility of adventure that it represents, and the infinite interplay between fiction and various realities.

I copied a shot from Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love in my film Return to Seoul—a scene with a reflection in a car window. Sometimes when directors shoot outside of their home countries they make their worst work, but in this case, the way Kiarostami shot in Tokyo was so fascinating.

-

2

Satyajit Ray

The Apu Trilogy

I only recently discovered the work of Satyajit Ray, during the first COVID-19 lockdown. I fell in love with it immediately. I could watch The Apu Trilogy again and again. I’m absolutely fascinated by the economy of Ray’s cinema—the simplicity of the form and the way he tells a story that captures the small moments of life but with so much complexity. I find that so inspiring. I would also compare these films to the Godfather trilogy. Like The Godfather, Pather Panchali is an example of pure mastery, in terms of structure and story and how every shot fits into place. And yet I have a bigger crush on the second one, Aparajito, just as I prefer The Godfather Part II to The Godfather.

-

3

Jean Renoir

A Day in the Country

This is my favorite Renoir film. It’s so short but so powerful, and each time you watch it, it breaks your heart. Maybe I have an affection for films that do that. It’s a movie that captures the here and now of its time as well as any I’ve seen. You just forget about the storyline and sometimes even the characters, because you’re purely in the moment. I’m so interested in films that achieve that. Many try, but it’s rare to succeed. A Day in the Country is just a block of time in its characters’ lives. You enter into it, and then what’s happening to them becomes your own memories.

I associate Renoir with the best of the realist directors. I don’t always watch a lot of naturalistic filmmaking, but when I do, it blows my mind and I think, this is exactly what cinema should be. I can’t say Renoir has had a direct influence on my films, but the way he captures life’s greatest complexities in the simplest form is a kind of horizon for me. If you believe, as Tarkovsky did, that cinema is the art that best captures time, A Day in the Country may be the ultimate film for you.

-

4

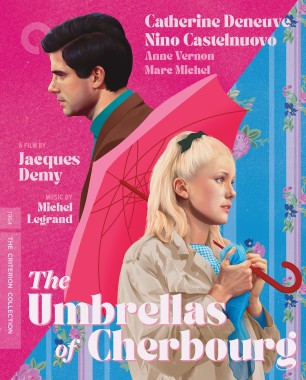

Jacques Demy

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

If I had to go to a desert island for the rest of my life, I would take The Umbrellas of Cherbourg with me. It’s a film I could sing along to every day, feel love with every day, and cry to every day. The Young Girls of Rochefort is a perfect twin. These two films convey very different things, and I have some friends who adore one and not the other. Rochefort is pure exaltation; Umbrellas, on the other hand, has some joy in the beginning, but you always feel the tragedy underneath it and then see how despair and regret eat away at the characters’ souls. I love both films, but if I had to choose between them, I would choose to cry.

-

5

Claire Denis

Beau travail

Claire Denis’s work exemplifies what Godard said about filming between the acts. In the best of her films, it seems like certain beats in the plot are missing. Watching Beau travail, the audience is hypnotized by its mood and by the act of entering into the minds of its characters. And of course, there is the dance scene at the end, which is an impossible model for any director to surpass; I made my first attempt at a dance scene in Return to Seoul.

I’d like to mention here that the Denis film I feel closest to is Trouble Every Day, which I think is a bit underrated. It’s one of the best films about the kind of desire that reaches such heights of intensity that it becomes madness and obsession. It’s always a shock when I watch it. You get the sense that Denis is feeling what the character is feeling, and it’s extraordinary and brave that she brought the audience into that extreme experience.

-

6

Hou Hsiao-hsien

Flowers of Shanghai

Hou Hsiao-hsien is one of my ultimate masters. I’ve watched all his films and love them all—from his youthful comedies in the eighties to the historical films of his midcareer period to his films from the nineties like Goodbye South, Goodbye and Flowers of Shanghai, which helped create modern Asian cinema. I love to lose myself in Flowers of Shanghai. It’s a film that captures the invisible and takes you down a path you don’t expect to go down. You just flow with the camera movements and the repetition of places, music, and shots. The whole film consists of two kinds of scenes presented over and over again. The repetition creates an intoxicating experience that feels like smelling the perfume of that time period.

-

7

Michael Cimino

Heaven’s Gate

I became a cinephile when I fell in love with New Hollywood films. Among the directors of those movies, Michael Cimino is quite unique, because he always succeeds in making us feel the love within a group of characters. He usually sets this up at the opening of a film, in just a few shots. I find that to be the heart of his cinema—this strong affection between characters, and how they are affected by the evolution of their bonds throughout the film. The only other director I see having this talent for so economically depicting love within a group in the opening scenes of his films is James Gray, who achieves this in The Yards and We Own the Night.

I had the rare experience of watching Heaven’s Gate at a screening in Paris where Cimino was showing the restored version. This film contains the ethos of New Hollywood—both its decadence and what led to its end.

The scene that really breaks my heart is the one in which Christopher Walken brings Isabelle Huppert to his house. He’s redecorated it for the occasion, but because he doesn’t have money for wallpaper, he’s dressed up the place with newspaper. His character dances around and is so nervous, trying to be elegant and clean up the dust. The most touching moment is when you see Huppert start to cry. You don’t know if she’s just so happy to receive love or if she’s sad because she understands that her future will be spent in these poor conditions. Maybe she’s feeling both those things at the same time.

-

8

Jean Grémillon

Remorques

I was very happy and surprised to see Jean Grémillon’s films in the collection. He’s less discussed than other masters of French cinema. But Remorques is an amazing film, and I wish more people would watch his work. I discovered this one during lockdown while watching hundreds of films with my partner in a studio in Amsterdam.

For me, this is the best film about amour fou. It’s a storm of sentimentality. There’s a straightforwardness to how Grémillon deals with feelings. I truly love that, because it’s rare. You really feel the emotions, and then they just grow inside you, and suddenly you’re taken over by the storm that the actors are bringing to life. There’s also a lyricism to his films, a poetry that imbues every shot.

What Jean Gabin does in this film is different from anything he did with other directors. There’s a vulnerability to his performance that feels daring. Throughout his career he often embodied a certain idea of masculinity and virility, so I was surprised to see that he could be so vulnerable on-screen.

-

9

Edward Yang

A Brighter Summer Day

This is a magnificent film. In response to the question “Do you prefer Edward Yang or Hou Hsiao-hsien?” I always give myself to Hou. But of course A Brighter Summer Day is a masterpiece.

This was the first film I showed when I opened my private cinema club in Phnom Penh, and it felt like a risky choice, because it’s four hours long. But people loved it. After those four hours are over, you emerge with the feeling that you’ve crossed through life. This movie has everything: life, death, love, friendship, youth, history, melancholy. And it explores the confrontation between American culture and Taiwanese and Chinese culture. It’s a full world.

I love Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders and Rumble Fish—two of the main influences on my film Diamond Island—and I love that we can feel A Brighter Summer Day in conversation with those films. Yang made his own Taiwanese version of these very masculine movies about youth.

-

10

Bob Rafelson

Five Easy Pieces

As I mentioned, New Hollywood is the foundation of my cinephilia, and I was so in love with the directors of that movement. But I only recently discovered Five Easy Pieces, at the end of writing Return to Seoul. I was so blown away by it—and it also has one of the best endings I’ve ever seen.

The film feels like this perfect encounter between the influence of the French New Wave (even though the film isn’t that crazy on a formal level, its shape is formed by the impulsiveness of the main character) and something very purely American, which can be found in the movie’s sense of individualism and its road-movie elements. Many New Hollywood films are character-driven, but Jack Nicholson’s Bobby Dupea is such a unique protagonist because of his anger and the deep pain that he does everything to hide. Bobby is trying so hard to be an asshole (and succeeds), but then there are scenes where you feel for him so much, which is a testament to the great writing and acting. I think this is one of Nicholson’s best performances.

I will also add that when I watched the film I was amazed by the similarities between Bobby and the protagonist of Return to Seoul. Everything that Nicholson’s character was doing in Five Easy Pieces, I could imagine Freddie doing in my film. And these characters have a similar relationship to music, which was completely coincidental and miraculous.