Kazuo Ishiguro’s Top10

Kazuo Ishiguro is a Nobel Prize–winning novelist, screenwriter, and song lyricist. Born in Nagasaki, Japan, in 1954, he moved to Britain with his parents when he was five years old. His books, translated into over fifty languages, have earned him many honors around the world, and The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go were adapted into acclaimed films. He received a knighthood in 2018 from the United Kingdom, and also holds the decorations of Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, from France, and the Order of the Rising Sun – Gold and Silver Star, from Japan. His most recent screenplay is Living, a reimagining of Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru. He has served on juries at the Cannes, Venice, and London film festivals.

-

1

Josef von Sternberg

Shanghai Express

Shanghai Express is a train movie, and I love train movies. I mean movies that are predominantly set on trains, in which the train becomes the whole world—North by Northwest doesn’t count just because the characters go on a train.

This film represents Marlene Dietrich at her best. Her performance here rivals the one she gives in Dishonored, and it shows her before she became too self-conscious about her image. Here, her world-weary eroticism is deployed to reveal layer upon layer of important character traits. You also have great performances by the rest of the cast, including Anna May Wong, who almost overshadows Dietrich in their scenes together. The film is beautifully shot, with an almost expressionist visual style. For its time, it was pretty brave, in terms of both its attitude toward sexual mores and its attitude toward race. And although it’s not a particularly long film, you feel at the end like you’ve come through an epic.

-

2

Frank Capra

It Happened One Night

I’ve chosen this one because it’s paradigmatic of a particular genre I really love—screwball comedy of the 1930s. Those films are a fascinating blend of romantic comedy and social commentary. During the Depression, Hollywood had to figure out how to keep entertaining the masses as the whole American Dream (which it had been romanticizing, to some extent) was collapsing. These movies are beautifully entertaining and full of love stories while also being protofeminist. The female characters are unlike the ones you see before and after that era. Typically, they’re women who, like Claudette Colbert in this movie, are determined to not let their lives be shaped by their social position or the roles that are being prescribed to them. Colbert’s character is an heiress who gets an education on the realities of Depression-era America when she goes out on the road and meets a lower-class hero played by Clark Gable. This film is a meditation on the instability of the American Dream, but it remains light and romantic and funny.

-

3

Stanley Kubrick

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Kubrick made many masterpieces, but this is my favorite. I watched it on television when I was quite young. It’s a remarkable blend of things that shouldn’t go together; it’s miraculous that Kubrick created the darkest vision you could have of nuclear war and combined it with out-and-out comedy. Watching it, I can see that it tops Fail Safe, which was made almost at the same time. Kubrick’s film interprets the same story as a very bleak comedy. I love the three roles played by Peter Sellers, which are completely different from each other. But the film also contains a few other remarkable performances, including Sterling Hayden as a general going haywire. Hayden always looks like a heavy object has just hit him on the head, and here he pulls that off to magnificent effect.

It’s a stroke of genius—the moment you realize the human race is going to be wiped out, you’re watching a cowboy whooping and riding an atomic bomb. What a way to announce the end of humanity!

-

4

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

This film isn’t nearly as well known as I think it should be. I was at a dinner just three nights ago where somebody mentioned the movie, and nobody else there had heard of it. For me, it’s the greatest English movie. Until I saw it, I thought all English movies were these modest black-and-white things, but this is so sweeping, both visually and thematically. It spans four decades in the life of a military officer, played by Roger Livesey, and it’s about his friendship with his German counterpart, played by Anton Walbrook, over the first half of the twentieth century and what happens to it as Nazism starts to take over Germany. The film was made in 1943, so the filmmakers didn’t know how the war was going to end yet. Walbrook’s character has become an anti-Nazi and a refugee. He’s lost everything, but their friendship continues. The film also explores the idea of Englishness—what’s magnificent about it and what’s downright stupid about it. I watched this film in the mideighties, when Martin Scorsese brought it out of obscurity and got it restored. It was showing in cinemas, so I went to see it, and it was a complete revelation. Then I went home and wrote The Remains of the Day.

-

5

Guillermo del Toro

Pan’s Labyrinth

I think Guillermo del Toro is one of the most remarkable artists in contemporary cinema. Everyone who sees Pan’s Labyrinth is overwhelmed by it. It’s a great movie about how human beings need fantasy. When life gets to be too much, we need to have a place to escape to. The film combines elements of fantasy, animation, and a war epic with themes of domestic trauma and a child’s point of view—and with every one of those things the film excels. What I find remarkable is the idea that fantasy is not just some pill you take to forget everything happening around you. The place the young girl in the film escapes to is where she works out who she is and what her values are. That’s what makes this both a tragic and a triumphant film. It celebrates human decency and courage while acknowledging how horrible the world can get.

-

6

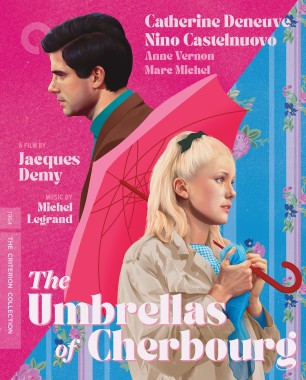

Jacques Demy

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

When people think of this film, they remember Michel Legrand’s music—the beautiful, exhilarating score that runs all the way through it. Every single line in the film is sung rather than spoken. People also often remember the very bold use of matching colors. But what’s so profound about the movie is that, in contrast to all this cinematic exuberance, it tells a story about how most of our lives cannot be controlled. It’s a film about fate. Even when you’re deeply in love, you’re unable to control things; circumstances will just push you around and circumscribe what you can and can’t be, what you can and can’t do. I think the ending is the absolute definition of bittersweet. I came to the film quite late, in the midnineties, after it had been restored. It wasn’t a movie I’d made any effort to see before. After I watched it, I just couldn’t believe it. It’s an incredible creation.

-

7

Alfred Hitchcock

The Lady Vanishes

I used to say this was my favorite movie Hitchcock made before he came to America, but it might actually be my favorite Hitchcock movie, full stop. It’s genuinely romantic, and it works as a romantic comedy. In so many movies from earlier eras, when you watch the way people court each other, it seems weird and makes it quite difficult to get into the relationship. But the chemistry between Michael Redgrave and Margaret Lockwood doesn’t feel dated at all. They’re full of the love of youth, and we’re convinced they’re attracted to each other.

The movie was made before the Second World War, and it ends with a real political statement about one of the biggest issues of the day: whether or not to appease Nazi Germany. The film addresses this effortlessly. It’s beautifully directed, and it has a sublime script and great character actors. I like some of Hitchcock’s later masterpieces, but this is the film of his I always come back to.

-

8

Yasujiro Ozu

Late Spring

I had to choose something by Ozu, who is probably my favorite filmmaker of all time. The father-daughter relationship at the heart of Late Spring is something that Ozu returned to several times, and it’s a subject that surprisingly isn’t dealt with in cinema very much. The film is about the generosity that’s required for a parent to let go of a beloved child, which is something all parents have to do if they care about their children’s happiness. Ozu typically tells these stories from the point of view of the father, usually played by Chishu Ryu, a great actor who reminds me of Bill Nighy. The father in Late Spring is faced with aging in isolation and loneliness, but he nevertheless makes a great effort to push his daughter into marriage because he knows that’s the way to secure her happiness. Love isn’t just about two people meeting on a train and deciding to get married; it’s also about things like this. People often have to make real sacrifices for the people they love, and all of Ozu’s deepest films touch on that.

-

9

Akira Kurosawa

Ikiru

I first saw Ikiru when I was a child growing up in England, and it had a profound influence on me. That’s not just because it was one of the very few Japanese movies I was able to see at that time, but because it said something really encouraging to me, something I held with me all through my student years and as I was becoming an adult. It told me you don’t have to be a superstar. You don’t have to do something magnificent that the world applauds you for. Chances are that life is going to be relatively ordinary—at least that’s what I had imagined for myself. For most of us, life is very circumscribed and humble and frustrating; it’s a daily grind. But with some supreme effort, even a small life can turn into something satisfying and magnificent. This is a very different message from, say, the one you find in A Christmas Carol, which tells us that if you should discover you’re a pretty shitty person, you can change yourself overnight and transform. The message is also different from the one in It’s a Wonderful Life, which says you might think your life is nothing but all along you’ve actually been doing wonderful things. Maybe that’s true, but usually it isn’t. I like that Ikiru says you can’t be passive about life. It’s not easy, but you don’t have to end up a shell. That’s what I hope a new generation of filmgoers will take from Living, the adaptation of Ikiru I made with the director Oliver Hermanus.

-

10

Jean-Pierre Melville

Le cercle rouge

This might be a controversial thing to say, but I find postwar French genre movies much richer and more real than the films of the French New Wave. It’s in the gangster films and thrillers where French cinema confronted all the bad things that happened under German occupation. France comes out of the war, and the New Wave starts to produce these films that don’t make any reference to history or the traces of the war that linger in French society. But that’s what these thrillers are all about. They explore honorable men operating in the criminal underworld as well as a very corrupt class of politicians and police who are treacherous and venal. These films are all about how much you can trust a comrade. Le cercle rouge is about the friendship between two guys—though maybe it’s a romantic relationship (it’s never made explicit)—and it contains a completely silent heist sequence that goes on for more than twenty minutes. There’s no sound in it, let alone dialogue! Alain Delon gives a virtuoso performance, one of his greatest. I could recommend any number of the French noirs by Henri-Georges Clouzot, Jacques Becker, or Julien Duvivier, but Melville is a true artist, and Le cercle rouge is my favorite of those films.