Azazel Jacobs’s Top10

Son of avant-garde filmmaker Ken Jacobs, Azazel Jacobs was raised in lower Manhattan surrounded by artists. He received his bachelor’s degree in film from SUNY Purchase and his master’s from the American Film Institute. His credits include The Good Times Kid (2005), Momma’s Man (2008), Terri (2011), The Lovers (2018), and French Exit (2020), along with both seasons of the television show Doll & Em (2014, 2015).

-

1

Aki Kaurismäki

La vie de bohème

La vie de bohème is a film I’ve loved for a long time. It’s probably my favorite Kaurismäki because it’s his most romantic and, in some strange way, his most hopeful. It also turned out to be the movie that helped me woo Lucas Hedges to be a part of French Exit. When we had our first meeting, I talked with him about influences and references, and I mentioned this film in particular and that it was showing at Metrograph. I didn’t really expect him to show up, but I got to the theater that evening and he was in the lobby, so we watched it together. When you’re showing someone something you feel so deeply connected to, it almost becomes your film. It felt like a strange audition. Kaurismäki’s humor is so particular; either it’s for you or it’s not. Immediately after the screening we ended up walking through the streets of New York talking about it and connecting it to Malcolm, Lucas’s character in French Exit. There was this idea that Malcolm lives in his suit, and that’s true of all the characters in La vie de bohème. This was our jumping off point.

-

2

Ernst Lubitsch

Trouble in Paradise

The way into the character of Frances in French Exit was Kay Francis. Trouble in Paradise also played at Metrograph, and that screening brought me back to it. The strength and individuality that Kay Francis put into everything she did, no matter how glamorous—that felt like something Frances had as well. I gave this movie to Michelle Pfeiffer to watch because I think of French Exit as a screwball tragedy, and I wanted her to see the daringness of Trouble in Paradise, the rhythms it played with, and the sense of celebration and love of filmmaking that comes through in a great screwball comedy like this one. You can also feel the presence of what was going on in the world at that time. I can only imagine what Lubitsch was going through thinking about so many people on the verge of being slaughtered in Germany, his homeland—and that carries a weight in the film, whether it’s readily apparent or not.

-

3

Jacques Tati

PlayTime

I grew up watching Tati films with my father [the filmmaker Ken Jacobs] and my mother and sister. These were films we could enjoy and find humor in as children. I’ve loved them for a long time, but the more experience I have as a filmmaker, the more it feels like what he pulled off was impossible.

Like Malcolm, Hulot is a person who is half in this world and half out of it. He’s being pushed by the wind, by forces bigger than himself. You don’t realize how much strength it takes to be in that kind of environment until you sit with a person like Hulot for a while. He is the backbone of the story, and though he may seem passive, he’s someone defining himself in a silent, watchful, and very powerful way.

-

4

Federico Fellini

La dolce vita

I wouldn’t say that this is the Fellini film that impresses me most (that would be Nights of Cabiria or The White Sheik), but this one deals with death in a way that’s similar to how I approached the subject in French Exit. La dolce vita looks at the reality behind glamour and the glamour behind reality: people wanting something and not getting it and trying to be something they aren’t, and then going through a process of letting go. That balance between fantasy and reality is something I always strive for. I gave the film to Michelle during an extended rehearsal period. With French Exit we had to walk a fine line between playfulness and seriousness. If I remember correctly, La dolce vita gave Michelle a bit more of an understanding of the world that we were bringing her into.

-

5

Samuel Fuller

Shock Corridor

Shock Corridor was a film that my cinematographer, Tobias Datum, and I studied in preparation. In the extras on the Criterion release, it’s said that it was shot in twelve days—and although we had more time for French Exit, it wasn’t much more. There is something Sam Fuller does, especially in this film, with his master shots; he shoots many access points within the long takes so that when he does singles and cutaways, it feels like there’s a lot more coverage than there actually is. This film is such an amazing illustration of how to do this well. For French Exit, I knew we didn’t have as much time as we’d like, but I wanted the story to shift and evolve, and I needed to figure out how to move the camera in such a way that it would feel like we had a lot more coverage than we actually did. For this I was completely influenced by Shock Corridor.

-

6 (tie)

Hal Ashby

Being There

-

Hal Ashby

Harold and Maude

Being There is a perfect film. I go back to it on a yearly basis and see more and more in it each time. It’s inspiring but also extremely daunting. It’s magical in a way that my films can only aspire to. The nature of our news has changed since then, but Being There is still completely on time.

Harold and Maude is another film I grew up loving and watching repeatedly. It also gave me a road map for French Exit. Rhythmically it’s just so distinct and so individual. It follows its own sense of humor, its own sense of self. It’s such confident filmmaking. It’s so clearly beautiful and alive. Hal Ashby had the precision it takes to balance tones and create his own. He’s completely in control, but at the same time the movie feels so egoless. There’s something so strong there, but it’s delivered with a very controlled humility, which you could also say about Kaurismäki’s films. In their own way, both of these directors make films in which you can feel how much they love what they’re doing and how much they respect their audience. You can also tell that Hal loved acting and marveled at it. I feel the same way when I’m watching actors; these artists who find moments of truth and intimacy while still being surrounded by all the people, machinery, and artifice that movies take.

-

7

John Hughes

The Breakfast Club

It wasn’t until I rewatched The Breakfast Club after not seeing it for years that I realized there’s a lot more to it than I could have ever known when it came out. I guess the tip-off was that Dede Allen edited it—that made me think, oh, this is something. I love art that looks easy, but as I mentioned with regard to Tati, the more experience I get as a filmmaker, the more it feels impossible.

The movie is full of long takes and particularly strong choices, not only in the casting and writing but also on the technical side, which you’d never know because it doesn’t call any attention to itself. The Criterion edition has hours’ worth of extra footage, which was amazing for me to see and feel. Hughes was so detail-oriented, in the way that Kubrick was, and although you’re seeing him do all this precise camera work, he appears incredibly present and alive, ready to pursue whatever occurs that feels truthful and interesting to him in the moment.

-

8 (tie)

Luis Buñuel

The Exterminating Angel

-

Luis Buñuel

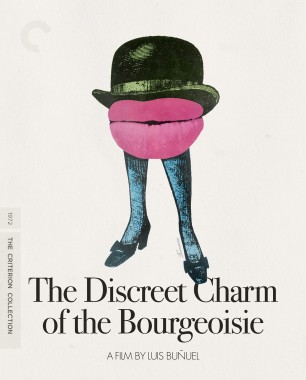

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie

The Exterminating Angel influences everything that I do. And The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoise—which is about these wealthy people searching for something amid dreams and impossible situations—gave me strength as we were approaching French Exit. It gave me the courage to go for it. I really needed that. And of course Buñuel had to be connected to our film, because there’s something surreal about the spirit of it. Buñuel was having so much fun, but he was always caring, not careless.

-

9

Charles Laughton

The Night of the Hunter

The Night of the Hunter is another film I grew up watching. It’s a story about truth and illusion, and about how a child’s vision is a reality that can get lost and stopped by adults. The Criterion disc has about an hour of footage that shows Laughton directing scenes. You rarely get the chance to see a filmmaker at work like that, especially such a master. It was great to just hear his voice and how he went over things again and again, in search of what he wanted, and not stopping until he got it. He was very clear and unrelenting, and seeing that gave me the strength to push for final cut, to do whatever I could to make sure that I was making the film I hoped to make. That footage of Laughton directing should be required viewing for anybody who is interested in filmmaking.

-

10

Stan Brakhage

By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volumes One and Two

When I was making this list, I was thinking about this idea that children can see the truth in a way that adults can’t, and that led me to the Stan Brakhage collection. His whole thing was returning viewers to a childlike vision, to the time before we’re taught to think “the sky is blue” or “the grass is green.” He wanted us to see all of these different colors and textures that we overlook as we get older. Because of my father’s close relationship with Stan, I was lucky to grow up knowing him, and through that I was able to study with him one summer out in Boulder. I think about those lectures all the time. He talked so much about the screen being not only a place where we look for truth and life but also a place of death, especially because everyone in these films—on-screen and behind the camera—eventually passes away. The screen itself, as its own type of gravestone.