Cinema Revolutionary: Fernando de Fuentes in Morelia

The films of Fernando de Fuentes find beauty in crowds. Rivers of people flow across the screen: soldiers wearily slogging along dusty roads or villagers parading euphorically behind the victor of a horse race. His camera loves to mingle among the celebrants at fiestas, wedding feasts, or even dull cocktail parties; it loves to track through big groups, scanning tableaux of faces and bodies. This director’s feeling for people en masse—the way they move, the patterns they make, the energy they generate—gives his films a charge of body heat.

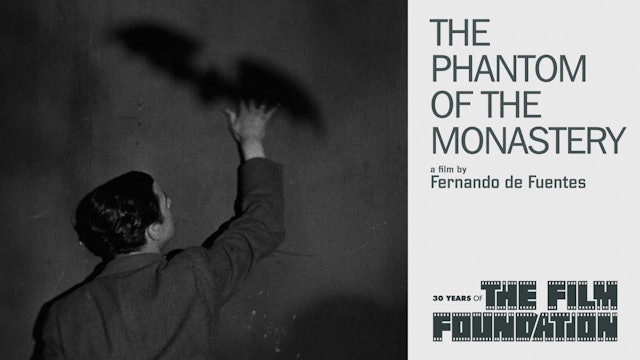

It is hard to overstate de Fuentes’s importance as a pioneer of Mexican cinema. In the space of a few years in the 1930s he created a defining portrayal of the Mexican Revolution and a seminal horror film (The Phantom of the Monastery, 1934), and, with Out on the Big Ranch (Allá en el Rancho Grande, 1936), he not only launched the genre of comedia ranchera but won the first major international award for a Mexican film, at the Venice Film Festival. This beloved movie would come to be seen as marking the start of the época de oro, the golden age of Mexican cinema, and the emergence of a film industry that would dominate the Spanish-speaking world for decades. Though recognized as landmarks, de Fuentes’s groundbreaking films are rarely screened in the United States. Nine of them were presented at the twenty-first Morelia International Film Festival, in October 2023, and the sampling revealed a cinema at once popular and sophisticated. Passionately dedicated to Mexico’s history, culture, and people, the films’ proud rootedness in a place and time nourishes a humanism that spills over borders and eras like a joyful, unruly throng.

Living History

Born in Veracruz in 1894, Fernando de Fuentes studied philosophy at Tulane University and later worked for a time at the Mexican Embassy in Washington, D.C. After his return to Mexico, he wrote poetry and journalism before entering the film industry. In 1932, he codirected Una vida por otra with the Hungarian John H. Auer, who would go on to a career in Hollywood, and he made his solo debut the same year with El anónimo. After this, de Fuentes embarked on the work that would make his name: a trilogy of films about the Mexican Revolution that portrayed the nation’s formative conflict with ambivalence and disillusioned realism, just two decades after the events they recreated. From the chamber drama of Prisoner 13 (1933), a caustic parable about the price of corruption, the trilogy builds to the teeming panorama of Let’s Go with Pancho Villa (Vámonos con Pancho Villa, 1936), with its magnificently detailed crowd scenes and chaotic battles. At the heart of these three films is not a political or ideological vision, but an intimate focus on people living through history, enmeshed in personal dramas of loyalty and betrayal, greed and idealism, loss and compromise. De Fuentes’s subtle, antiheroic treatment of the conflict, laced with bitter ironies, aroused some controversy and censorship.