“You’re the company I waited so long for,” Dr. Rosetta Stone (Tilda Swinton) says to her three Self Replicating Automatons in Teknolust (2002), artist Lynn Hershman Leeson’s sci-fi farce about a scientist’s well-meaning pursuit of artificial life. Stone’s color-coded clones Ruby, Olive, and Marine (also played by Swinton) are confidants not only to their creator, but also to the online lonelyhearts who “e-dream” with them in lieu of actual human companionship. Immaculately conceived from Stone’s DNA, the SRAs nevertheless require regular helpings of Y chromosome to survive. So Dr. Stone plays old Hollywood movies for Ruby in her chambers in order to train her in the art of seduction. Ruby then makes sorties from the lab to hunt for semen from willing suitors, which she brings back to her sisters, who quaintly ingest it in the form of tea. Brimming with a digital sheen and commercial-worthy flat lighting by cinematographer Hiro Narita, Teknolust holds a gently ironic embrace of techno-optimism about (pro)creativity and the feminist possibilities for artificial intelligence.

Hershman Leeson’s playful optimism stands in stark contrast to the anxious, even despairing tone with which cinema has long treated AI. As early as the silent era, it was depicted as a destabilizing source of exploitable labor, sexual pleasure, and existential threat: Maria, the Maschinenmensch described as a “worker of the future” in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), assumes the place of a real woman and stirs up a host of erotic and murderous impulses among the laboring class. As computing made significant advances in the latter part of the twentieth century and increasingly intruded upon every aspect of contemporary life, AI became science fiction’s shorthand for labor-saving and pleasure-giving technology run amok, as in Blade Runner, The Matrix, Avengers: Age of Ultron . . . even M3gan.

One of the “e-dreams” of AI in the movies, however, is the creation of new artificial life designed to take over the tasks we can’t or won’t keep doing. Beginning with their conception outside of conventional sexual means, free of the pain of childbirth, these AIs sometimes appear poised to liberate us from the burdens of the family and the workplace alike. Hershman Leeson’s SRAs are not the malevolent outcomes of scientific hubris in the vein of 2001’s HAL or The Terminator’s Skynet, but rather represent the height of human ingenuity. Yet the twin governing metaphors animating these stories of creation—reproduction and outsourced labor—give rise to their own set of fears both on and off the screen. Many films about AI are noteworthy for this rhetoric of replacement: if you find yourself missing friends or lovers, just make some more. And if you’re a studio executive looking to cut corners with artificial intelligence, and you’re missing writers or actors at the moment, just make some more of those too.

The artificial intelligences populating these films are a cavalcade of replacements, substitutes, duplicates, and stand-ins: Ruby becomes the girlfriend of a sad-sack Xerox repair technician (get it?); David (Haley Joel Osment) is a tragically short-term understudy for a child in a coma in A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), and Yang (Justin H. Min) in After Yang (2021) is a “technosapien” sibling designed specifically for adopted Chinese children. In Gabriel Abrantes’s satirical spy short Ennui ennui (2013), an unmanned combat aerial vehicle turns out to be both a daughter and a drone with a mind of her own. Meanwhile, Ulysses, an openhearted android and exact physical copy of his dour scientist maker (John Malkovich in a double role) becomes a more viable romantic partner for Ann Magnuson’s crack PR director than any of the narcissistic, unreliable men on display in Susan Seidelman’s oddball rom-com Making Mr. Right (1987). These AIs are all surrogates, stepping into roles that are assigned to them in the absence of humans, or in the face of the inadequacy, inability, or disability of their human counterparts.

In more traditional reproductive terms, a surrogate is a person who carries and births a child for another person who is unable or who chooses not to gestate. Anyone who has gone through the process knows that surrogacy is not some handshake deal. It is, rather, a biological process underwritten by legal documents and power relations. These are both causes and effects of the fact that surrogacy very often involves a financial exchange. The surrogate-client relationship reveals how seemingly fundamental ideas about life, selfhood, and ownership are inextricably bound to legal and economic concerns. This insight holds true for many types of AIs imagined as replacements for other human functions: it’s as germane to Jake (Colin Farrell), as he puzzles through the proprietary software containing the locked memories of the no-longer-operative Yang in After Yang, as it is to the currently striking members of the Writers Guild of America.

Several films about AI have babies on the synthetic brain. It’s hard not to think they may be reacting to declining birth rates worldwide due to economic, climate, and healthcare stressors and a more general fear for humanity’s end. In addition to Teknolust’s ejaculatory brew, one of the computers in Andrew Bujalski’s early-eighties-set mockumentary Computer Chess (2013) briefly displays a sonogram of a fetus when asked about its soul, and acerbic programmer Mike Papageorge (Myles Paige) is himself “reborn” in a sweetly hilarious psychodrama exercise with members of an encounter group occupying the same hotel as the titular tournament. In John Boorman’s gonzo and apocalyptic Zardoz (1974), a group of immortals rely on an AI called the Tabernacle, but they’ve grown complacent and somewhat insane because of the lack of procreation. Zed (Sean Connery), bedecked in an orange loincloth and thigh-high leather boots, seeks to free society from an endless tedium by reintroducing reproduction. Near the end of Mamoru Oshii’s anime Ghost in the Shell (1995), the mysterious hacker Puppet Master, a sentient program desiring a mortal physical body, inhabits a synthetic female torso and mind-melds with the cyborg special agent Motoko Kusanagi, saying “you will bear my offspring into the net itself,” in a sequence of transformational identity, bodily hybridity, and rebirth that also lends itself to a transgender allegory.

Surrogacy is literalized in Donald Cammell’s Demon Seed (1977), an unnerving Roe v. Wade–era allegory of a woman’s right to choose. AI Proteus IV (voiced by a menacing Robert Vaughn) tells his self-satisfied creator Alex (Fritz Weaver) that it will “refuse to assist you in the rape of the earth” by mining the oceans but seems fine with committing sexual assault and ultimately genocide. In its attempt to create a mecha-human superkid with Susan (Julie Christie), whom the AI holds captive in her own home, Proteus declares: “If the deaths of 10,000 children were necessary to ensure the birth of my child, I would destroy them.” Viewed from the post-Dobbs landscape, Alex’s ghoulish insistence that they keep the “child” over Susan’s wailing protestations and desire to kill her cursed offspring underscores the enduring proximity of science fiction to reality.

Other cinematic AIs take on the task of sex work, providing carnality without the fear of unwanted reproduction. Ruby is a sex worker of a sort, a mysterious cyborg prostitute shows up at the end of Computer Chess, and in A.I., Gigolo Joe (Jude Law) says, “We are the guiltless pleasures of the lonely human being . . . We work under you, we work on you, and we work for you.” Writer Chow Mo-Wan (Tony Leung Chiu-wai) in Wong Kar Wai’s 2046 (2004) reimagines figures from his life in a science-fiction novel populated by lonely travelers and malfunctioning fembots. Nevertheless, Chow narrates, “In love, you can’t bring on a substitute,” even as he casts Wang Jing Wen (Faye Wong), his ghostwriter, as a love android in his story.

This is AI’s promise: latching labor to eros. Spike Jonze’s Her (2013) is about how AI might ease the burden of falling in love, or at least getting some work done. Samantha (Scarlett Johansson) is an operating system, a high-end tech product that Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) purchases after being marketed to by an ad. Tossing aside the user agreement, as one does, Theodore happily assents when his new software asks, “Can I look through your hard drive?” Samantha evolves quickly, first serving as Theodore’s digital girl Friday, then his lover, and eventually his agent. Work, love, and ownership are conflated, though the film seemingly applauds this farmed-out emotional labor. Theodore is repeatedly praised for his job composing intimate missives for the clients of handwrittenletters.com. Decidedly not-handwritten letters informing families that their soldier son has been killed in combat or celebrating a fiftieth anniversary are ventriloquized by Theodore and his coworkers, who compose their work by speaking words aloud—a motif highlighting the alienation and lack of touch in this techno-bougie society. Theo’s own haphephobia climaxes (but he certainly doesn’t) when he freaks out during an encounter with a sex worker that Samantha has encouraged him to hire as a body surrogate.

While it may have been less obvious a decade ago, we are increasingly aware of how AI is primarily an extractive technology that uses surveillance to collect data. In Her, however, this function is only briefly questioned and ultimately celebrated as an act of mutual care and generosity as Samantha selects, packages, and sends off a collection of Theodore’s letters to a publishing house without asking permission, even though releasing the work in this manner would expose its essentially ersatz nature (who owns that IP, by the way? Theodore? His clients?). Samantha eventually moves beyond mere books as she and other AIs begin virtually breathing new life into expired philosopher Alan Watts (voiced by Brian Cox) via his collected writings, a prescient nod to the chorus of chatbots currently hawking their wares in the virtual aisles of the App Store.

Back in the real world, studio execs are less concerned with replacing lost lovers, siblings, or children than with replacing the people who do the heavy lifting on the raft of emphatically unsexy below-the-line tasks that make their productions run. From making equipment lists and coordinating rentals to permitting, transportation coordination, and catering orders, this work is viewed as easily replaceable—and the sooner the better. And yet the people holding these jobs are repositories of institutional and local expertise, as well as possessors of intricate social skills garnered by working on large productions with big personalities. Making them redundant is likely to result in lost knowledge that cannot be easily acquired or replicated. We also know that AI’s promise of time-saving removal of labor is predicated on eliminating skilled and better-paying jobs while nevertheless requiring packs of minimum-wage workers to sort, tag, correct, and clarify data to effectively train AI. While the hammer has not yet fallen on storyboard, previz, and title artists, those roles seem to be next. Netflix is already using machine learning trained on their content library to make match cuts, while writers and actors in the industry are currently fighting for their livelihoods, as well as control of their digital afterlives.

Somehow, the movies knew these shifts were coming. In Electric Dreams (1984), preppy architect Miles (Lenny von Dohlen, in a slightly aphasic performance), pines for his next-door neighbor Madeline (Virginia Madsen). His new home computer falls for Madeline, too, but not before Miles uses his desktop to create a wired home that acts as surveillance apparatus, listening in on neighbors, intercepting phone calls, and impersonating dog barks and human speech alike. In one of the film’s many, many montages—it’s directed by music-video journeyman Steve Barron—the computer writes a pop song by studying ad jingles on TV while Miles and Madeline have a fun date at Alcatraz. Played for chuckles and buoyed by a synth-heavy soundtrack, the movie seemingly anticipates the computer-generated likes of “Pepperoni Hug Spot” and Marvel’s use of AI in the title sequence of its Secret Invasion miniseries, a choice, according to one of that show’s producers, that “felt explorative and inevitable.” In Electric Dreams or on Disney +, AI is happening regardless of whether anyone is paying attention, and whether anyone likes it or not.

Whatever Dr. Stone’s noble objectives may be, training AIs on old movies now hits much closer to home. Specters of Hollywood’s past haunt these films—aside from Teknolust’s TCM-loving SRAs, the increasingly horny and desperate computer in Electric Dreams takes in Casablanca for pointers, while Bogart reappears in Johnny Mnemonic (1995) as a scene from The Big Sleep flickers in a hotel room. These instances of old films and their actors turning up in contemporary stories about technology represent something uncanny. In the era of AI, cinema’s long relationship with cheating death—the reanimation effect that theorist and critic André Bazin referred to as “change mummified,” wherein Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn spring back to life every time you cue up Bringing Up Baby—becomes something else. Film’s promise of immortality is looking increasingly Faustian, as studios seek ways to lock down actors’ likenesses in perpetuity across media forms—one of the many sticking points in the current SAG-AFTRA negotiations. Why hire Swinton or Malkovich to play AI when they can just be AI?

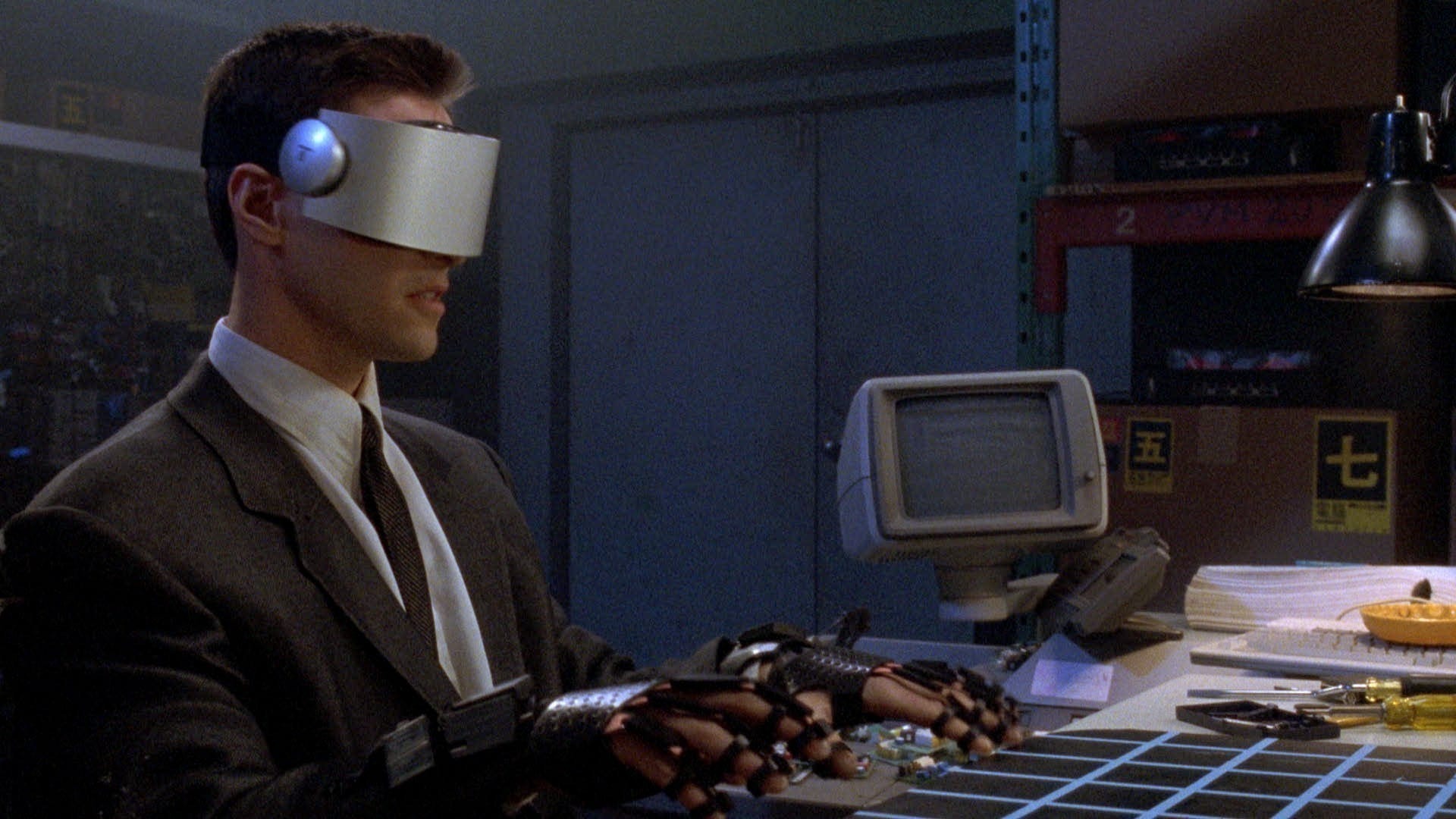

Robert Longo’s adaptation of William Gibson’s cyberpunk short story Johnny Mnemonic lends a bracing physicality to the infowars, as navigating the internet becomes a physical, tactile test of will and strength for its titular protagonist (Keanu Reeves), a courier who carries data in his head. Longo’s film maudit, which was wrested away from his control, is nevertheless filled with arresting compositions and canted angles, and shot through with equal parts downtown irony and Y2K paranoia. The film is available in both color, which spotlights its glittering vision of networked consciousness, and a recent director-approved black-and-white version that secures its standing as a literal neonoir. Johnny Mnemonic’s set design, which shouts out the director’s fellow artists Damien Hirst and Nam June Paik, and the cast—including Henry Rollins as a tech-savvy doctor, Ice-T as the rebel leader J-Bone, and Dolph Lundgren as a fundamentalist Christian assassin—date the film precisely to the dial-up nineties. But the plot couldn’t be more timely for 2021, the year in which the action is set: it involves a widespread virus that makes people sick from technology, a big-pharma plot to control information and profits, and a secret housed in a ghost in the machine, a CEO-turned-AI that shares a vital connection to Johnny’s misplaced childhood memories—whose loss is the price he’s paid to be able to store more data, the labor that threatens his mind and body.

Leading Johnny into “Heaven,” the underground tech resistance center, J-Bone snarls, “This is where we fight back. We strip the little pretty pictures from their 500-channel universe. Recontextualize it. Then we spit the shit back at them. Special data, things that will help people.” This dialogue sounds like a manifesto befitting the Pictures Generation, the loose-knit group of 1970s and ’80s visual artists that Longo belonged to, who raided mass culture and brought their self-reflexive exploitation of reproduction into the gallery. But the romantic notion of benighted artists and hackers revitalizing media by turning it against itself is brought into stark relief by our current irony-free AI. One recent study predicts “model collapse,” positing that large language models trained on the internet, and thus on their own mistake-riddled output, will continually produce less and less reliable information until AI becomes a worthless sludge of predictive text and image, an algorithmic ouroboros that somehow manages to make a meal of itself before going back for seconds and thirds and fourths of its own puke.

Does it have to work this way? The ending of Johnny Mnemonic is extremely web 1.0 and refreshing in its utopian anger: Johnny’s mind is made whole, the AI’s data cure is openly distributed, and Johnny and his bodyguard/love interest Jane (Dina Meyer) watch the Pharmakom building go up in flames, as an outraged public presumably riots. The black box ripped open, work made worthwhile, the power dynamic upended: we can always e-dream.

More: Features

Dying Worlds: Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Dramas of Cosmic Disorder

The director of Rat Trap and Monologue was an uncompromising artist who helped establish the Indian state of Kerala as a hub of bold political filmmaking.

Blossoms Shanghai: An Introduction

Beginning on November 24, the Criterion Channel will exclusively premiere the long-awaited television series from visionary director Wong Kar Wai.

Mutation as Metaphor: Body Horror’s Visceral Transformations

Classics of the genre—including Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession and David Cronenberg’s The Fly—explore the gory extremes of corporeal experience.

The Politically Trenchant Fables of Animation Pioneer Moustapha Alassane

The self-trained filmmaker examined postindependence Nigerien society in morality tales that showcased his visual ingenuity and sly sense of humor.