The Labyrinth and the Plague

Of all the weird scenes that populate seventies science-fiction cinema, the most bizarre might be in 1971’s The Omega Man. Based on Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, the film imagines a world in which fallout from a distant war has eradicated most of humanity, turning survivors not into vampires (per Matheson) but feral albino Luddites.

But the strangeness occurs before we even know this much. Robert Neville (Charlton Heston) careens through the city’s bright and desolate streets, an easy-listening eight-track playing in his red convertible, only to stop in front of a movie theater. On the marquee is Woodstock, the 1970 film of the 1969 concert, a quintessential sixties event.

“Great show,” he remarks to no one. You might expect Neville to riddle the theater with his assault rifle, just as he did moments before, shooting at a ghoulish silhouette in a window. (You also might expect it based on Heston’s later incarnation as president of the NRA.) Instead he gets the projector running and takes a seat, and suddenly . . . we’re watching Woodstock.

Country Joe and the Fish announce their brand of “rock and soul music.” Neville grimaces, hand on the barrel of his gun, as a hippie raves about his recently elevated consciousness: “This is really beautiful . . . just to really realize what’s really important,” he rambles. “The fact that if we can’t all live together and be happy, if you have to be afraid to walk out in the street, if you have to be afraid to smile at somebody, right, what, what kind of a way is that to go through this life?”

The gun stays put. As the hippie speaks, Neville mouths the words along with him. We realize he’s done this lonely ritual many times before.

“Yup,” he concludes, “they sure don’t make pictures like that anymore.”

In other words, the sixties are over. Here come the bonkers seventies.

The decade’s science-fiction legacy is partly obscured by the extraterrestrially inclined blockbusters appearing near its end: George Lucas’s Star Wars and Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). But before that, filmmakers were using the genre to construct bleak, paranoid scenarios right here on earth: claustrophobic labyrinths and lethal plagues. Consciously or not, some films read like responses to the ongoing war in Vietnam, corruption in the shadow of Watergate, environmental degradation and urban decay, and the rise of a new machine age. Some of the films snap back at the excesses of the sixties, too: it can’t be coincidence that the slavering creeps whom Neville battles every night call themselves the Family, à la Charles Manson.

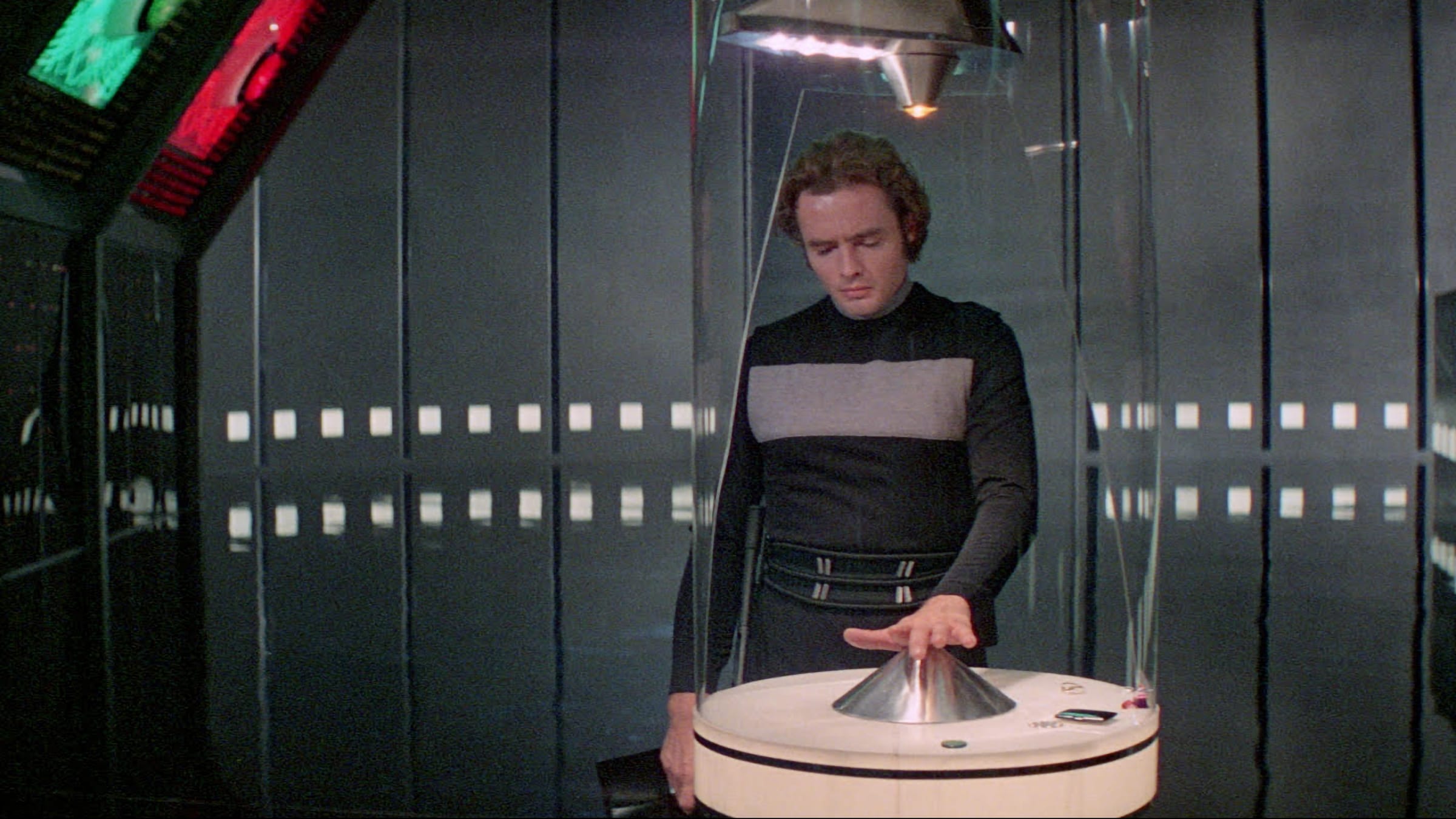

Even though humans reached the moon in ’69, most of these movies remain earthbound, as if the gravity of the world’s problems wouldn’t permit such easy, escapist fare—at least for a while. Indeed, the jarring prologue of George Lucas’s 1971 debut, THX 1138, is a snippet of an old Buck Rogers serial, pounding home the difference between a tale of derring-do and the imprisoning nature of man’s own inventions.

Star Wars, Lucas’s next science-fiction title, would set a new standard for special effects; until then, some of the design can be delightfully primitive. Made just a year before Star Wars, Logan’s Run often looks chintzy: we can clearly see the wires holding up the hockey-masked participants in the Renewal ceremony, the gravity-defying ritual that ends the charmed lives of citizens upon hitting thirty. And in Z.P.G. (1972), the city is so polluted with smoke that you can’t even see any buildings, obviating the need to build a futuristic streetscape. But the satirical jabs still hit their mark. A trip to the Statemuseum features taxidermied housecats, and a display entitled “Gasoline Pump 1971.” (“I am now going to take this gasoline pump,” the guide patiently explains, “and pour gasoline into this car.”) The seventies are long over, now preserved in a museum, where they can be viewed with amusement as a total fiasco. It’s a dead decade.

Except, of course, it isn’t. In the real world, we are now treated to a rich array of oddball, uncouth cinema from that anxious period, via the Criterion Channel’s ’70s Sci-Fi series: a crop of nihilistic plague narratives (No Blade of Grass; The Omega Man; David Cronenberg’s debut, Shivers), a notorious problem child (Stanley Kubrick’s eye-popping A Clockwork Orange), and corporate-conspiracy exposés (Soylent Green; Rollerball, in which company names—“Energy”—are abstractions). THX 1138 and Logan’s Run present hermetically sealed environments from which the hero (and sometimes heroine) must escape. There’s significant overlap with other genres, notably the western (Michael Crichton’s Westworld, George Miller’s Mad Max) and the exploitation flick (Death Race 2000, the execrable cult oddity A Boy and His Dog). Then there’s Demon Seed, in which Julie Christie’s character is terrorized in her own home by a supercomputer that wants to impregnate her—in sixties speak, it’s Rosemary’s Baby starring 2001’s HAL.

As Heston’s Neville would say: They don’t do pictures like that anymore.

Above: THX 1138