RELATED ARTICLE

Reign of Destruction

By Steve Ryfle

The Criterion Collection

D irector Ishiro Honda gathered his crew and gave them an ultimatum. He was about to put his career at risk, and he would only work with those who approached his current project—a movie about a radiation-spewing prehistoric reptile that destroys Tokyo—with the utmost seriousness, as he himself did. “He told them . . . ‘Read the script. If you are not convinced, please let me know immediately and leave the project,’” Kimi Honda, the director’s wife, recalled years later. “He only wanted those who had the absolute confidence to work with him on this film.”

It was the spring of 1954, and Honda was readying to direct Godzilla. As the first movie of its kind produced in Japan—and one of the most expensive movies made in the country to date—it was an audacious project for the filmmaker, for Toho Studios, and for a domestic film industry that had been left devastated and demoralized after World War II but was now resurgent. During the fifties and sixties, the masters of postwar Japanese film (Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, Masaki Kobayashi, Mikio Naruse, Nagisa Oshima, Kon Ichikawa, and many others) would produce a bumper crop of exemplary, enduring cinema, acclaimed at home and abroad. Concurrently, a generation of studio-contracted directors would crank out commercial program pictures for the domestic market—dramas, comedies, period pictures, gangster pictures, and musicals—with efficiency and hit-making skill. Honda was among the latter group, but he would forge a unique path as Japan’s foremost director of kaiju eiga, or giant-monster movies. While the works of Kurosawa et al. were limited to art-house distribution abroad, Honda’s films played to mainstream moviegoing audiences in the U.S. and across the West, and they have subsequently become ensconced in the pop-culture pantheon. Honda’s influence is undeniable: as one of the creators of the modern disaster film, he helped set the template for countless blockbusters to follow, and a wide array of filmmakers—including John Carpenter, Martin Scorsese, Tim Burton, and Guillermo del Toro—have expressed their admiration for his work. Yet the full scale of his achievements has only recently begun to be appreciated.

But it all started with

Honda’s sober-minded approach to the original Godzilla. Other directors

had begged off the project, believing it was ridiculous, and that it would

likely end up a laughingstock. But to Honda, this was no joke. Working with the

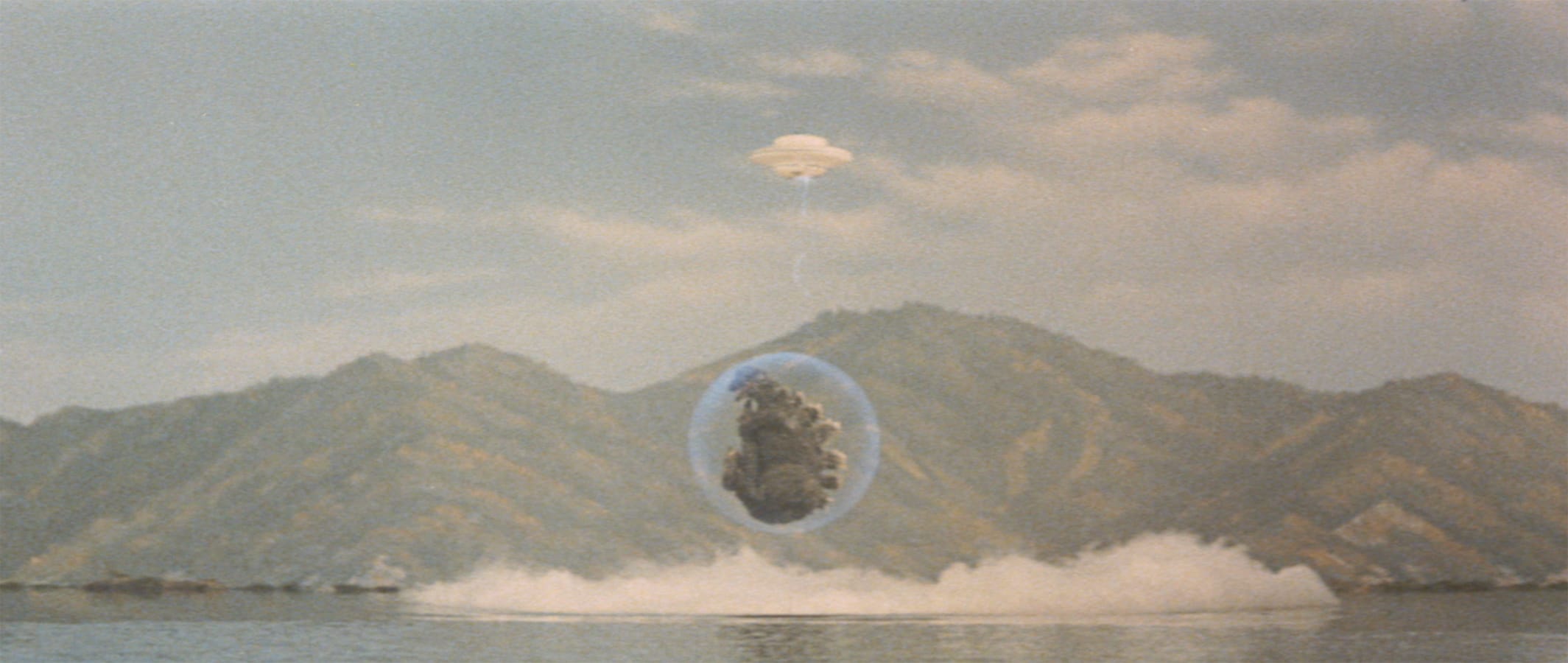

special-effects genius Eiji Tsuburaya, who devised the genre’s signature

combination of “suitmation” (a man-in-suit monster) and precisely constructed

miniature sets, Honda created a monochrome masterpiece of sci-fi horror

punctuated by extensive destruction sequences that elicited real-life fears of

nuclear terror. Images of Tokyo smoldering in the wake of the monster, of

irradiated civilians setting off Geiger counters, and of the Japanese military

overmatched by the seemingly indestructible foe helped turn Honda’s

entertainment spectacle into a cautionary tale about the atomic power that had not

long ago been unleashed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“Honda became known as a director with a subtle way of coaxing performances from actors, and one who never raised his voice on set.”

Godzilla (1954)

Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965)

The War of the Gargantuas (1966)

Destroy All Monsters (1968)

All Monsters Attack (1969)

Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975)

“Honda’s films were distributed around the world more widely than those of any other Japanese filmmaker prior to Hayao Miyazaki.”