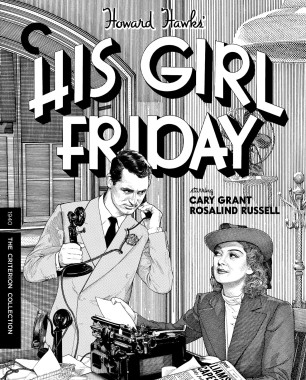

The Funny Man with the Pardon: Billy Gilbert in His Girl Friday

As Howard Hawks was preparing to make His Girl Friday, his 1940 version of the classic Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur play The Front Page, he was determined not to repeat what he felt had been a problem with his earlier comedy Bringing Up Baby. Although we now think of that film as a classic, it was a commercial failure when it was originally released, and Hawks thought audiences rejected it because all the characters were “crazy,” so “that poor guy and the girl don’t reach for a laugh of any kind.” The events in The Front Page had been inspired by Hecht’s real-life experiences during his days as a newspaper reporter in Chicago, and Hawks clearly felt that by grounding the characters in plausible reality he would not only be true to Hecht’s story, he would also make it easier for audiences to connect with what might otherwise seem to be outrageous events. “We got more fun for our leading characters, Grant and Russell, by keeping the other characters straight,” Hawks explained. “Outside of one reporter and the funny man with the pardon . . . they were all pretty legitimate.”

The “pardon” is a slip of paper that serves as

the deus ex machina upon which the entire plot of The Front Page ultimately turns. And in His Girl Friday, the “funny man” who carries it is a

forty-six-year-old comic actor named Billy Gilbert. At the time His Girl Friday was made, Gilbert had

been acting in shorts and features for ten years. This was his 170th screen

performance, and he appears in two scenes for roughly six minutes. But he is so

hilarious in that brief time that if you ask the average viewer who the film’s most

memorable characters are, they’d likely include the FM with the P.

Gilbert was born in 1894. The son of show business professionals, he entered vaudeville at twelve and over the next two decades began to make a name for himself on Broadway as well. The man who brought him to Hollywood and changed his life forever was probably the greatest comedy film producer of all time, Hal Roach.

A large man with a big head, wild black hair, a mustache, and raccoon eyes, Gilbert was naturally cast as the antagonist to Roach comedy stars. But if there was one thing that sealed his comic typing, it was his voice. As big as he was, his voice was bigger. This might well have been genetic—his parents were singers in the Metropolitan Opera. When he unleashed that voice in anger, the results were volcanic. One word that invariably accompanies descriptions of his early characters is blustery—no one could bluster like Billy could bluster. He blustered at Charley Chase, and he blustered at Our Gang. In his spare time, he went to Columbia and blustered at the Three Stooges. Most famously, in Laurel and Hardy’s Oscar-winning short The Music Box he was the man who hates pianos. No, let me correct that. He was the man who HATES PIANOS!!! Such is his rage at our poor heroes, who are only trying to deliver said piano to his house, that the viewer could be forgiven for imagining actual steam escaping from his ears.

By the midthirties, Gilbert had become a welcome presence in features as well as shorts, and in 1937 he sneezed his way into cinema immortality by voicing Sneezy in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Gilbert’s character in His Girl Friday derives from the play, where he goes by the name “Pincus.” The world Pincus will enter is the pressroom of the Criminal Court building, as reporters, policemen, and politicians await the hanging of accused cop killer Earl Williams. The corrupt mayor and sheriff need the execution to happen for their own political purposes. When a messenger named Pincus arrives with a reprieve from the governor, they endeavor to get rid of him until Williams is dead. He agrees to leave and the mayor suggests he visit a place he knows where “you can get anything you want,” which in 1931 meant a speakeasy, a brothel, or both. Pincus returns toward the end, the worse for drink. Insisting that he can’t be bribed, he drives the play and film to its conclusion.

In the first film version, made in 1931, the part is played by Slim Summerville, himself a skilled comedian known for slow-talking country bumpkin types. And that’s how he plays Pincus. His very presence, rustic and dim, is a comic contrast to the hyperactive Chicago characters, and we know immediately he is out of his league. But when Billy Gilbert, now called Pettibone (a funnier name—just trust me on this one), enters His Girl Friday, we see the brilliance of Hawks’s casting. Because Pettibone is not the hayseed played by Summerville. Nor is he the traditional outsized Gilbert character. Instead he’s a timid soul—a little man in a big body. The contrast is funny from the moment he opens his mouth. In the original, Pincus only speaks when spoken to. But nobody can keep their mouth shut for that long in a Howard Hawks comedy, so the director, along with screenwriter Charles Lederer, ensured that Pettibone has something to say, usually wrong or irrelevant, between or during lines by the mayor and the sheriff (it’s entirely possible that some of this was ad-libbed by Gilbert, improvisation being something Hawks generally encouraged).

But while the expansion of the dialogue helps turn a one-note role into a fuller and more immediately amusing one, I would suggest that much of what makes Gilbert so effective in this film could be traced to his physical expressiveness, which he mastered in his years with Roach. One signature that runs across the Roach comedies is the value of the reaction shot. Roach, his players, and his directors realized that laughter driven by a big sight gag could be extended by cutting to the reaction of the comedian directly affected by it. Think of the multivalent camera looks of Oliver Hardy or the fogged visage of Stan Laurel, whose rising and falling eyebrows signaled the slow grinding of rusty gears behind them. Other Roach comics found reactions that suited their own personas.

There’s a crucial difference, however, in the editing style of Roach and Hawks comedies. The deliberate pacing of Roach and his directors called for a gag in one shot to be followed by the reaction in another. Hawks’s fleet comedy style doesn’t work that way. With all his actors in a master shot jumping on or through each other’s lines, Gilbert reacts continuously to what he hears or thinks he hears, shifting from befuddlement to astonishment to anger within one shot. And because his comprehension usually runs a beat behind his reaction, those shifts are often hilariously wrong.

Hawks’s choice to have the other characters in the film play their parts “legitimately” pays dividends here. In a traditional comedy team, you have a straight man and a comic. The questions and comments of the straight man triggerthe jokes of the comic. In Gilbert’s first scene, what Hawks effectively gives us are two straight men doing their best to ignore the comic. Gilbert is fitting the “jokes” into their barely existent pauses. The traditional straight man has to deal with the comic throughout the scene or sketch. By contrast, the sheriff and the mayor in His Girl Friday are desperately trying to get rid of the comic and are frustrated by Pettibone’s incessant reactions, both in word and action, to everything they say.

In the second scene, it is clear that the clown has won the war. Hawks told Grant and Russell that this was Billy’s scene and you can see them lay out and let him run. They can’t take their eyes off him and neither can you.

Later in 1940, Gilbert would memorably play Herring in Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. He continued in features throughout the forties, adding television in the fifties. He retired in 1962 and passed away in 1971. IMDb lists 229 places you can go to see the great Billy Gilbert but if you don’t have that kind of time, may I suggest you look at the clips above if you haven’t already (and why haven’t you?). A man is about to walk through that door clutching a piece of paper and all he wants is a moment of your attention.