Stool pigeons are among the lowest of the underworld’s bottom-feeders, despised alike by the crooks they inform on and the cops who make use of them. Leave it to Sam Fuller, ever the maverick, to make a hero of a stoolie—or rather a heroine. In

Pickup on South Street (1953) he created the role of Moe, the streetwise peddler of neckties and information, for Thelma Ritter, Hollywood’s queen of character actresses.

Few actors have earned so much love with so little screen time. (George Cukor’s charming 1951 The Model and the Marriage Broker gave Ritter a rare and welcome leading role.) That she was nominated six times for best supporting actress without ever winning seems in a way like a perfect tribute to her expect-the-worst persona. She won by losing. Ritter was in her forties when she made her screen debut as a harried shopper in Miracle on 34th Street (1947), but seemed older, with that preserved-in-brine quality that long-time New Yorkers get, at once worn out and indestructible after decades of riding the subway and fighting through the crowds. Born in Brooklyn in 1902, Ritter worked on stage and in vaudeville in the 1920s, and later on radio, and raised two children before making her first movie. She immediately cornered the market in lovably blunt, wisecracking maids and sidekicks, shooting down genteel pretensions with a voice that emanated straight from the asphalt.

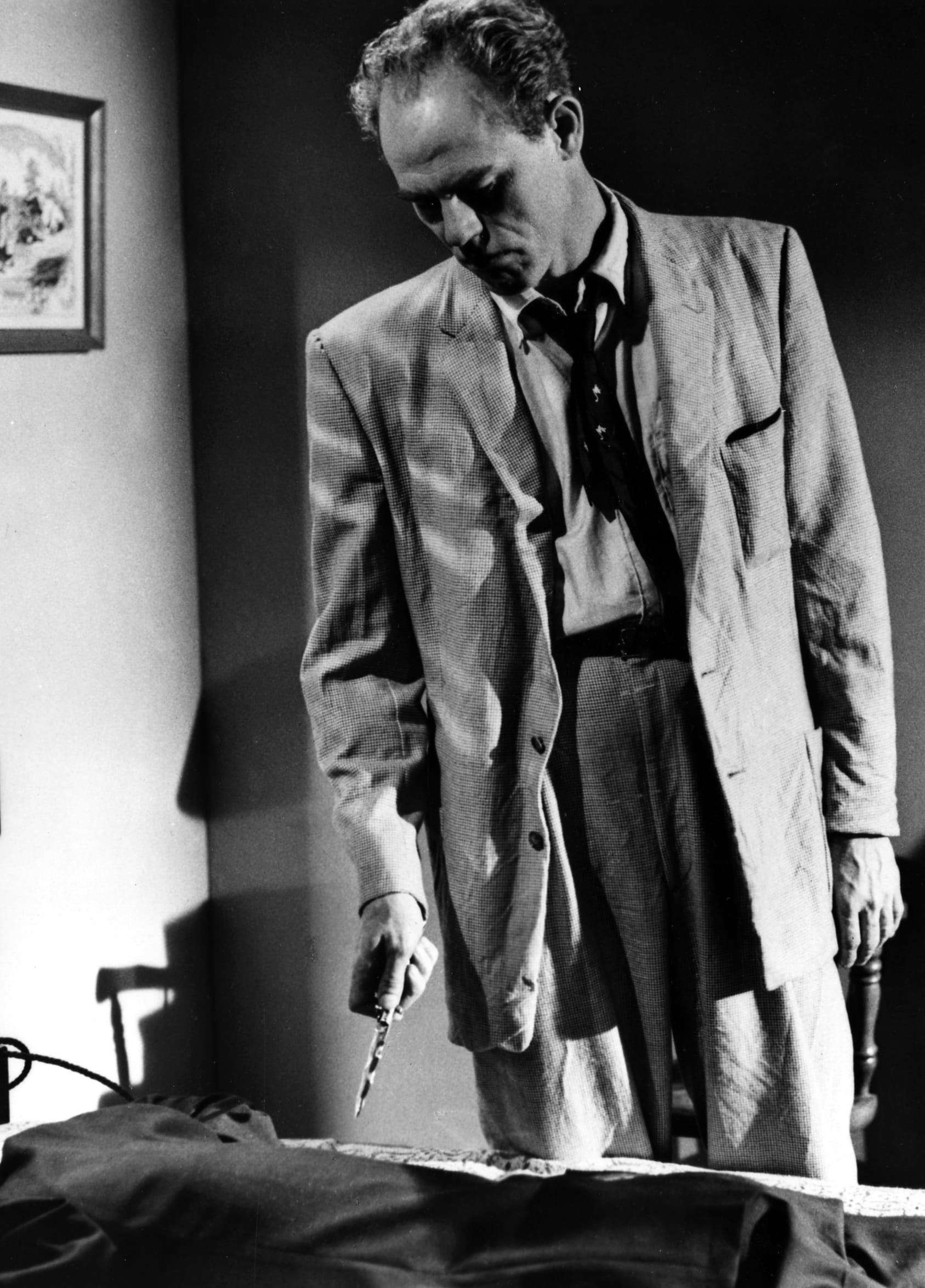

Pickup on South Street is a movie about marginal people, in which—on the face of it—America is saved from communist espionage by a petty thief, a tramp, and a mercenary police informant. The star is Richard Widmark, irresistibly raffish as the pickpocket Skip McCoy, but Ritter shows him a thing or two about larceny, filching the movie out from under his nose. In her first scene, as she haggles and banters with the cops who want her help fingering a “cannon” who “buzzed” a woman’s wallet on the subway, Ritter is her familiar, adorable self. The frumpy floral-print dress and squashed hat, the squawky voice with its Brooklyn accent thick and pungent as a pastrami sandwich, are the same as they were in A Letter to Three Wives (1949) and All About Eve (1950), the same as they will be in Rear Window (1954) and Pillow Talk (1959). But here she transcends her usual character turn; in just a few scenes, Ritter takes a slangy comic sketch and shades it into a fully human portrait, baring the weariness and vulnerability of an aging woman alone in the world, bone-tired from hustling to survive. This is all the more affecting because Ritter’s type was tough as leather, always armed with a punchline and a gimlet eye; rarely did she reveal any weakness.

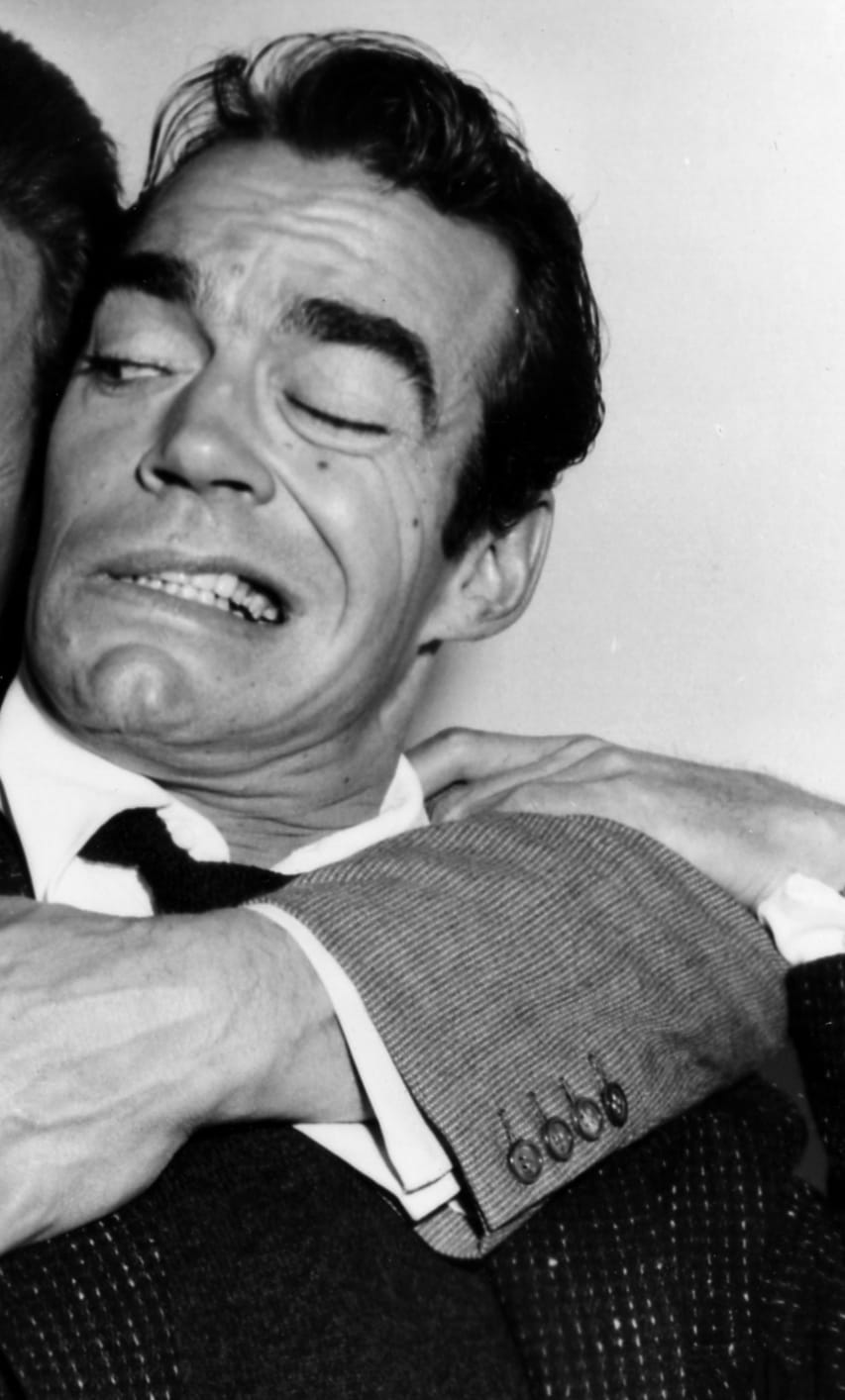

Moe cherishes a bankroll with which she plans to buy herself a plot in an exclusive cemetery. “If I was to be buried in Potter’s Field, it’d just about kill me,” she quips, dead serious. Beneath the black humor of her fixation is the real sadness of a woman whose only remaining ambition is to die decently, but whose bedrock sense of right and wrong elevates her to a heroic end. It comes in a justly celebrated scene that is one of the finest Fuller ever wrote, a worthy gift to the actress he so admired. As Moe comes home to her little room after a long day fruitlessly pushing her neckties, the way she moves and breathes, the look on her face, all speak of exhaustion, frailty, aches, and heart trouble. She props herself up in bed, listening to a record of a singer wistfully crooning the faux-French chanson “Mam’zelle.” This could all be terribly sentimental; it could be laughable when she then confronts a ruthless commie spy who tries to bribe and then threaten her into selling out Skip McCoy, who has inadvertently stolen some pilfered microfilm.

Instead, it is a scene that breaks your heart cleanly but mercilessly. As Moe begins to talk about her weariness and her ailments, how hard it is to keep going, her sense of running down like an old clock, the camera moves in on her slowly in an unbroken take that lasts more than a minute. In close-up her face has a delicate, weathered prettiness. Her lips visibly tremble, and her voice cracks as she laments, “I gotta go on making a living so I can die,” but she faces with simple courage and dignity not merely death, but her worst fear: ending up in Potter’s Field with the rest of the poor, the unknown, and the unloved. Into her last line, she puts more genuine, unaffected pathos than many actors muster in a career. When Skip, in his first unselfish act, later rescues her coffin from the municipal barge in the gray dawn and takes it back for a proper burial, the film pauses to honor her as she deserves.

The art of the character actor is to create, with only brief lines or scattered scenes, the sense of a whole person. Some do it with looks and mannerisms that invoke a type, the way a caricaturist can suggest a familiar face with a few bold lines. Others, like Thelma Ritter in Pickup on South Street, do something different: they give us a whole life in a flash, like a landscape glimpsed from the window of a moving train, gone in an instant but impossible to forget.