The Sprightly Civil Servant: Norman McLaren at the National Film Board of Canada

One of the key issues in understanding a national film culture—who are we?—is understanding who we are not. In the case of Canadian cinema, part of that definition has always been clear from the outset. “We are not Hollywood,” that unavoidable behemoth down south. The need to figure out what a uniquely Canadian cinema might look like was, for a time, such a point of national pride that it resulted in the creation of government funding bodies, the likes of which Americans could only dream of.

Today, however, in the post-Reagan-Thatcher-Mulroney years, such government largesse is constantly under threat. It’s not even so much that the funds have dried up, although there is not nearly as much grant money as there used to be. It’s more of an attitude that anything creative and meaningful can only emerge from the private sector. Since the 1980s, we have been taught to expect that national governments are lumbering and inefficient, and that they can only stifle individual initiative. Certainly genius could never flourish on the federal dime.

But the career of the great Canadian animator Norman McLaren gives the lie to this anti-government bias. McLaren’s earliest works from the 1940s may have been utilitarian in nature, promoting war bonds and wartime price controls. But the films were never just “propaganda.” And in time, McLaren was able to abandon that didactic impulse altogether and focus on experimental works that stretched the boundaries of the cinematic form. We can look back at this body of work, spanning five decades from 1933 to 1983 and almost all of it created under the auspices of the National Film Board of Canada, and see exactly how the vision of a free man could in fact thrive and find a wide audience with the support of his government.

Like his NFB colleague John Grierson, McLaren was Scottish by birth, and the two men initially worked in Great Britain making films for the Film Unit of the General Post Office. Grierson, who many credit with inventing the term documentary film, was equally inspired by the poetic realism of Robert Flaherty and the precision montage of Dziga Vertov. As such, he was drawn to men and women who could communicate concepts in accessible yet unconventional ways. He hired McLaren after seeing some of his student films, and the two men worked together at the GPO from 1936 to 1939.

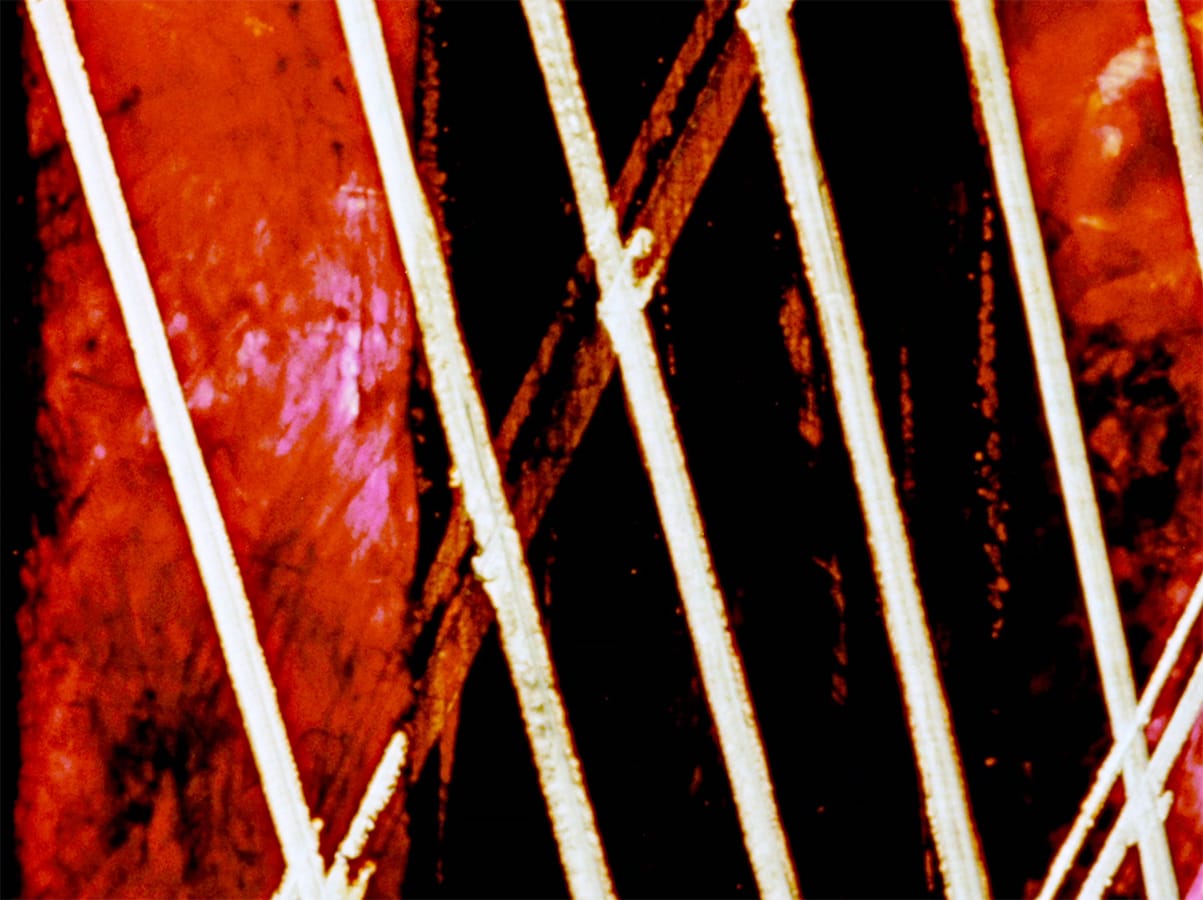

In 1938, Grierson was hired by the Canadian government to conduct an audit of the nation’s promotional film services. After providing his report, he returned to Scotland but was invited back to implement his own recommendations. So he moved to Canada in 1939 to form the NFB. McLaren followed him shortly thereafter, in 1941, as did director Guy Glover, McLaren’s life partner. Initially the Film Board was making war propaganda films, many aimed at the U.S., which had still not entered the war. McLaren’s unit was tasked with making animated commercials encouraging Canadians to buy war bonds. Among these films are two of McLaren’s early classics, Hen Hop (1942) and Dollar Dance (1943). Both were drawn directly on celluloid, frame by frame, although with their broad pen work and solid color backgrounds, they only hint at the intricacies of McLaren’s later films.

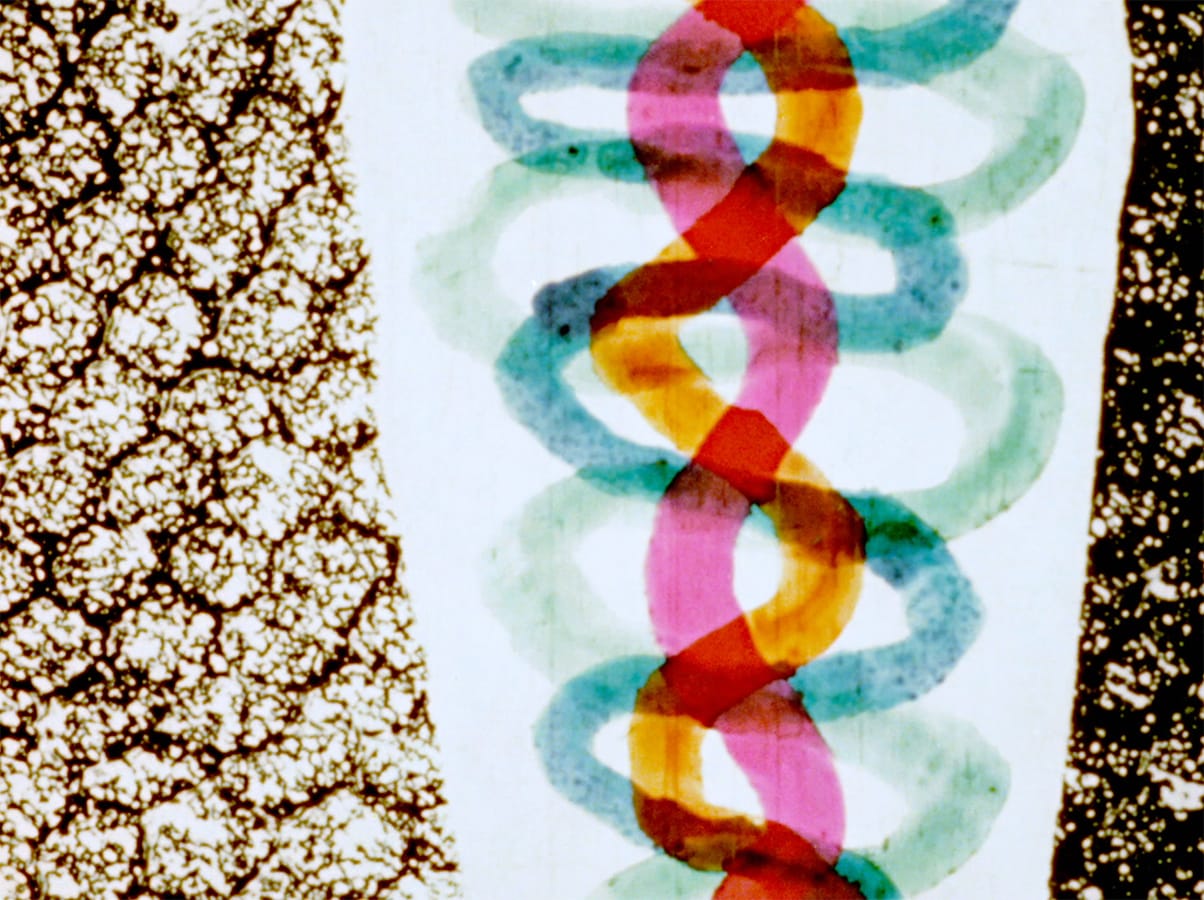

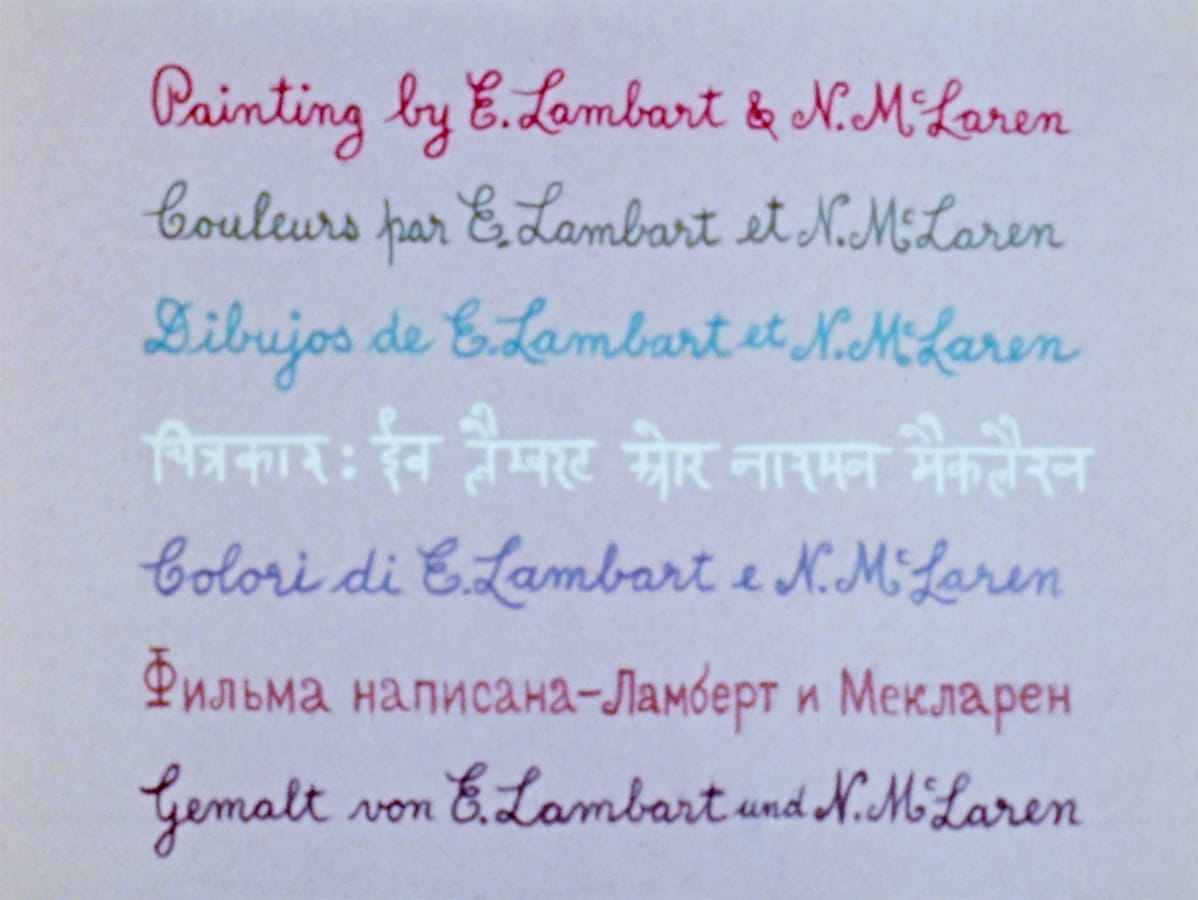

Starting in 1942, McLaren was given the freedom to assemble a team of animators with whom he would work for most of his career. These included Jim McKay, George Dunning, and Evelyn Lambart, McLaren’s collaborator on Begone Dull Care (1949). This group, with McLaren as the head animator and mentor, came to be known as Studio A, and worked within the NFB with relative autonomy. The NFB’s stated mission was “to produce and distribute and to promote the production and distribution of films designed to interpret Canada to Canadians and to other nations.” They answered the call by creating a distinctively Canadian animation form for an international audience, with a focus on a combination of modernist experimentation and populist modes of address.

“There is an emphasis on pleasure in McLaren’s work, understood as a dialectic between the known and the unknown, the radical and the familiar.”

Begone Dull Care