In a tribute to Elvis Presley that aired on Turner Classic Movies, Kurt Russell says that “an Elvis movie is always worth watching because of Elvis.” This insight gets at a core truth about a much maligned and mostly dismissed body of work. From his big-screen debut in 1956 to his final film in 1969, the rock-and-roll superstar appeared in thirty-one feature films, and partly due to the breakneck pace at which they were made (about three a year), some of them are flimsy. But most were, in fact, box-office hits, and almost every one of them brims with Elvis’s charisma and humor. He was a unique cinematic figure, with a self-invented movie persona all his own.

More than half a century removed from their original context, these films can be appreciated on their own terms—and for the rare thing Elvis achieved with them. Few stars can single-handedly justify a film’s existence, in the way Kurt Russell (who appeared on-screen alongside Elvis as a kid and went on to play him in a 1979 television movie) described. John Wayne could be compelling in any film he was in, but he contributed to a preexisting genre—the western—and without him, those movies would still make sense. Elvis, on the other hand, created his own genre, and the genre died with him. Perhaps the closest antecedent to the “Elvis movie” is the on-screen collaboration of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis: sixteen films that all created their own self-contained reality and traded on the audience’s familiarity with the stars’ personas. Martin and Lewis were a duo, though. Elvis stood alone.

There also had never been anyone like him. He started as a vital and controversial regional star, but in 1955, when RCA bought him from Sun Records for $40,000 (an unprecedented sum at the time), he was on the verge of global superstardom. The year 1956 was a whirlwind: television appearances, riots, pandemonium. Protests from priests, PTA mothers, disc jockeys, and racists weren’t successful in dampening his popularity. His songs dominated the charts, but could this typhoon be harnessed by a movie? Elvis’s evolution into a Hollywood star began when famed producer Hal Wallis signed him to a contract that same year. He wanted to ease Elvis into acting, so he arranged for him to play a supporting role in the ensemble drama Love Me Tender.

Directed by Robert D. Webb, the film tells the story of four brothers, and Elvis plays Clint, the baby of the Reno family. It opens with the older brothers holding up a train, followed by endless scenes of horses galloping from right to left and back. Imagine a teenage fan in 1956 sitting through all this galloping, with no Elvis in sight. Finally, at eighteen minutes and thirty-two seconds, a small, muddy figure enters from the right, struggling behind a handheld plow. It’s the opposite of a star entrance.

Elvis is obviously green in Love Me Tender, hesitating before lines, a little self-conscious. But Mildred Dunnock, who plays the matriarch, once told a story that reveals his unconscious understanding of what acting is—or should be—even in this early role. For one scene, he was instructed to pick up a gun and ignore Dunnock’s plea to put it down. On the day of filming, Elvis, a devoted mama’s boy, obeyed her command instead of following the script. Though he’d made a mistake, he was listening. Dunnock explained the anecdote like this: “It’s a story about a beginner who had one of the essentials of acting, which is to believe.”

Elvis commits admirably in Love Me Tender. In one scene, he doesn’t just hug his costar Richard Egan, he flings himself at him. He also comes to vibrant life in four musical numbers that were shoehorned into the film, even though he had made it clear he did not want to sing in his movies. The songs are Hollywood-hillbilly, and his moves are anachronistic, but it doesn’t matter. What you get in these moments is a sense of Elvis’s joy in himself, his innocent pleasure in entertaining people.

“And introducing Elvis Presley” is how his credit reads in Love Me Tender. But in his subsequent movies, his name would appear above the title, in a font size that expanded to absurd extremes as the years went on. There would be no waiting around for Elvis’s presence anymore; he would be there from the first scene. Some of the films revolved around well-known elements of his own biography: the ending of Jailhouse Rock, for instance, is taken directly from an incident in Elvis’s life that made headlines, in which he swallowed a tooth cap and needed to have an emergency surgery.

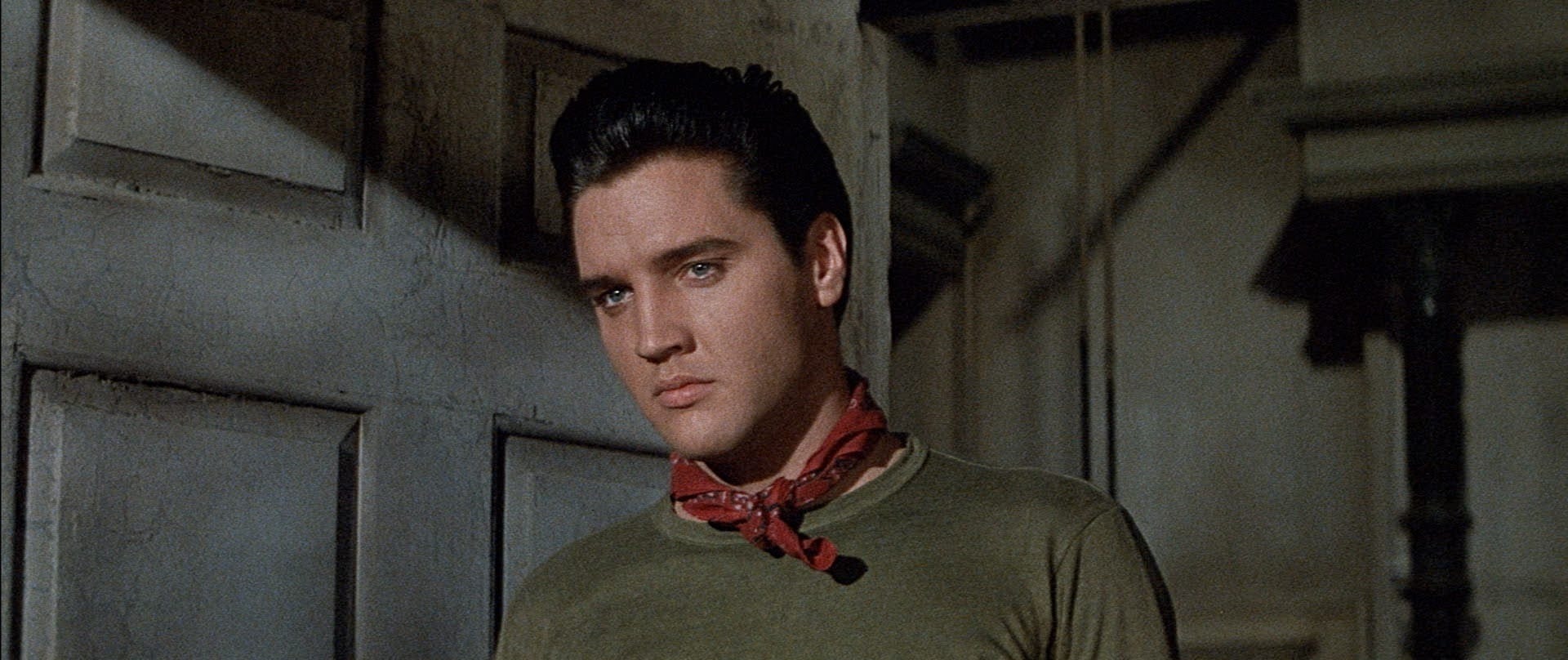

The first phase of his film career stretched from 1956 to 1958, and it established him as a force to be reckoned with at the box office, and also as a unique figure in the burgeoning teenage-rebel movie landscape (Martin Sheen said that, when he was a kid, he had hoped Elvis could fill the gap left by James Dean’s untimely death). This era closed out with King Creole, which has probably the best production values of any Elvis movie. Adapted from a best-selling novel by Harold Robbins, and featuring songs written by rock-and-roll visionaries Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller (who wrote “Hound Dog” and “Jailhouse Rock”), the film was helmed by the most high-profile director Elvis would ever work with: Michael Curtiz. The Hollywood veteran respected Elvis as a phenom and thought carefully about how to frame and light him. And for his part, Elvis handles this meaty role as a rebellious high-school student—and the difficult scenes it required him to bring to life—without pushing. He’s comfortable in his own skin; he listens and reacts, the building blocks of any good performance. The inexperience evident in Love Me Tender is gone.

Elvis’s career paused in 1958, after he was drafted into the Army and shipped off to Germany for two years. When he returned to the U.S., he struggled to find his footing again at the box office, but also managed to make some of his best movies. One of these is Wild in the Country, a film that stands as an outlier in his career. Like King Creole, it comes with some pedigree: the screenplay is by the great American playwright Clifford Odets. Though it’s hard to know how much tinkering was done to the script, many lines ring with his unmistakable prosody, and Elvis does an expert job riding the rhythms of Odets’s language. Elvis plays a troubled kid who has dreams of being a writer and attends therapy sessions to avoid jailtime. The character gives a speech in which he remembers his mother working in the fields, rubbing buttermilk on her arms to stave off sunburn, and Elvis’s delivery is riveting. He’s quiet and pained. It’s personal work.

King Creole and Wild in the Country show Elvis could handle complex material. But in the early sixties, a shift occurred that would end up defining his on-screen legacy. After the runaway success of 1961’s Blue Hawaii, what later became known as the “Elvis formula” coalesced, perpetuating itself in Girls! Girls! Girls!, It Happened at the World’s Fair, Fun in Acapulco, Viva Las Vegas, and Girl Happy, before calcifying in the best-forgotten Clambake, Double Trouble, and Paradise, Hawaiian Style. These movies may not have earned much critical acclaim, but at their best they exude pure, uncomplicated pleasure in a way that feels more extraordinary today than it did when they were released. These formula movies are unembarrassed by their own silliness and triviality, and there is something relaxing about this, particularly in our self-serious cinematic present. Elvis being at the center makes it all okay. When people refer to “Elvis movies,” it’s the formula movies they’re talking about. And it’s within the context of these silly narratives that Elvis’s sui generis status is most clearly seen, where he shines most brightly.

The Elvis formula movie usually boils down to these parts:

- An “exotic” location (Hawaii, Las Vegas, Acapulco)

- Elvis playing a singer moonlighting as a race-car driver or pilot or boat captain

- The “triangulation” of Elvis by numerous women (except in Viva Las Vegas, Elvis rarely appeared in a one-on-one love story)

- A song in every scene

- Low stakes

- Extreme chastity (lots of kissus-interruptus, coitus interruptus being totally off the table)

- A goofy sidekick, there to accentuate Elvis’s beauty and competence

- The nonexistence of real-world problems

Watching these movies alone in your apartment can be a surreal experience. They are meant to be seen in a drive-in on a hot summer night. There, they make perfect sense.

Viva Las Vegas is the high-water mark of this group of films. George Sidney, an experienced director of musicals, treated it as a legitimate musical, as opposed to just another Elvis formula movie. The film includes elaborate production numbers and choreography. Elvis is paired with Ann-Margret, a performer of equal fire and passion. Their chemistry sizzles, as does their obvious mutual appreciation. Elvis had to work to hold the screen with her, and he loved the challenge. Unlike in any other movie in Elvis’s career, his costar is given two solo songs, as well as a duet with him (the charming “The Lady Loves Me”). Viva Las Vegas doesn’t feel like a formula. It feels like sheer fun. The movie inspires fans to ponder a few what-might-have-beens, one of them being: What if he and Ann-Margret had gone on to make a series of films together, capitalizing on their chemistry? (A probable reason this never came to be: his controversial manager, Colonel Tom Parker, disapproved of how much screen time Ann-Margret received in Viva Las Vegas; it “took away” from Elvis.)

Despite his commercial triumphs, Elvis did not have the film career he envisioned for himself—he had hoped to become a serious actor. Though he may have been naive about the viability of his ambitions, he wasn’t entirely delusional; after all, several pop stars before him had found success and respect in Hollywood. Bing Crosby won an Oscar in 1945, and Frank Sinatra had received one too, just three years before Elvis made his film debut. Elvis wanted to follow in their footsteps. He had what F. Scott Fitzgerald called “a mystical conception of destiny,” and it’s not hard to see why. He came into the world with a stillborn twin brother and wondered if he had been spared for a special purpose. He achieved his unprecedented fame so quickly, as if it was meant to be. As music critic Dave Marsh observed, if there was anything Elvis really wanted it was to be “an unignorable man.”

Formulaic movies were not the only option that had been available to him. For one of his early screen tests, Elvis performed a scene from N. Richard Nash’s play The Rainmaker, and there was talk of him playing the lead role in the film version, which ultimately went to Burt Lancaster. But there was way too much money on the table to allow him to handle risky material. Colonel Parker—listed as “technical adviser” on most of his films—wanted the movies to be made as cheaply as possible, with Elvis front and center in every scene. The star’s public image became a paradox. The man who epitomized the provocative spirit of modern American music—who, in Lester Bangs’s words, “alerted America to the fact that it had a groin with imperatives that had been stifled,” and who caused riots at his concerts just by wiggling his hips—was now the face of safe, unthreatening, conventional filmmaking.

In the late sixties, as Elvis neared the end of his contract, the Elvis formula fell apart, and some really interesting films were the result, two of which were the screwball comedy Live a Little, Love a Little, and the misleadingly titled The Trouble with Girls, a really interesting ensemble film in which Elvis, surrounded by character actors like Dabney Coleman and Vincent Price, is at the center but is not the lead. These are fine films, and they’ve been unfairly forgotten.

It’s hard not to think wistfully about missed opportunities in Elvis’s movie career, the most well known of which is the male lead role in the 1976 A Star Is Born remake (Barbra Streisand wanted him to star alongside her). Even more intriguing is the idea of him playing Val in Tennessee Williams’s Orpheus Descending, a play eventually made into The Fugitive Kind, directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Marlon Brando and Anna Magnani. Years after the film’s release, Lumet had this to say about that possibility:

What would it have been like if Val had had Presley’s simplicity, lyricism, and rather strange otherworldly quality? There’s a speech in the play [in which] Val talks about this mythical bird that has no legs and can therefore never come to rest and just hovers in the sky until it dies because there was no place for it to land. In content it evoked such a memory of what I felt of Presley when I watched him work: something otherworldly, unhuman (not inhuman), a kind of restless spirit that could never rest anywhere . . . And I thought how extraordinary it might have been to hear it from someone exactly like that but totally unaware of his own separation from the rest of us.

Elvis was indeed “separated” from us, in life and in the movies. And certainly none of the films fully evoke the explosiveness of his live performances. But here and there, his on-screen work does capture the flame, and that’s what makes it timeless. I think of the “Young Dreams” number in King Creole, in which he sits at the edge of the nightclub stage, gleaming in a white shirt and silky neckerchief. As he sings, he glances around him, searching for connection in the audience. His physical response to the music is fluid, his neck undulating, his whole body in gentle, continuous motion, even though he never stands up. It’s almost a shock, how easily he inhabits his unreal situation, how freely he shares himself. Elvis is in the spotlight alone, unembarrassed, unironic, justifying the film’s existence by his presence, giving pleasure to the people who seek it.

Not a shabby legacy, when you think about it.

More: Features

Galatea’s Revenge: Actresses Talk Back

In a collection of behind-the-scenes documentaries now playing on the Criterion Channel, legendary female performers assert their agency over their screen personae and find freedom in the glamour and artifice of their profession.

A Year’s Worth of Essential Reading

As we come to the end of 2025, we’re looking back at some of the essays and interviews we’ve shared with you over the past year.

Room Tone 2025

Celebrate the holiday season with this special treat from our production team.

Dying Worlds: Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Dramas of Cosmic Disorder

The director of Rat Trap and Monologue was an uncompromising artist who helped establish the Indian state of Kerala as a hub of bold political filmmaking.