For decades, the Yugantar films were unviewable, the prints languishing in basements in threadbare condition, until the German scholar Nicole Wolff spearheaded a restoration effort at the Arsenal Institute in Berlin in 2011. Eight years later, new digitizations of Tobacco Embers and Is It Just a Story? premiered at the 2019 Berlinale, catalyzing a slew of screenings across the globe, and a long-overdue—yet extraordinarily timely—reappraisal of Dhanraj’s work. When I first saw the Yugantar films during the pandemic, as part of a free streaming program on the Arsenal website, they overwhelmed me with the force of time capsules, as if they were ancestral objects I’d dug up in my own backyard. They felt startlingly immediate because they anticipate so many of the terms that are now buzzwords in the fields of documentary and feminism. They are cocreatively made and defiantly intersectional in their visions of social justice, and they demonstrate with unassuming directness an idea that is fetishized yet increasingly elusive in contemporary feminist politics, especially in the West: an understanding of gender inequities as inseparable from those of class, caste, and religion, and a vision of womanhood as pluralistic, with no standard shape.

These ideas were part of the DNA of the “autonomous women’s movement” of the ’70s and ’80s, which saw women all over India fight to carve out a space for feminist causes within ongoing struggles for labor rights and civil liberties. Dhanraj and her collaborators’ filmmaking and activism grew from this movement, which confronted the limits of representation right from the outset: it surged in the wake of the Emergency of 1975, a brutal period of repression enforced by Indira Gandhi, India’s first (and, so far, only) female prime minister. Gandhi presided over a litany of human-rights abuses during her tenure, from violent clearances of slums to forced sterilizations of both men and women. While the slogan “the personal is political” inaugurated a new wave of feminism in the West, Yugantar filmed women whose private lives had been inescapably politicized, their wombs and homes invaded by the state and by corporations.

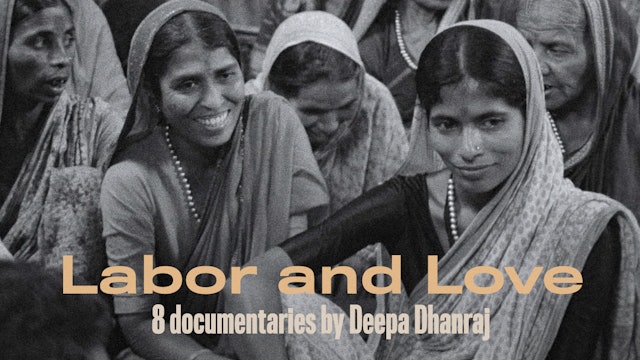

What the Yugantar films capture isn’t simply the explosion of the personal into the political, but also the binding of individuals into a collective. These documentaries were intended as tools for mobilization rather than as art objects; Dhanraj and co. would haul 16 mm reels across the country on buses, screening them in local-language dubs in slums, union meetings, and women’s centers, in the hopes of provoking conversation and action. Yet, because these films emerge from collective formations at every level—they are about collectivization and are directed collectively—they are inherently complex, even experimental, in form. Yugantar members would spend months living with the groups depicted in each film, learning about their lives, coscripting scenes, and even renting local cinema halls to screen rushes and solicit feedback. Is It Just a Story? turned personal accounts gleaned from sessions with the women’s group Stree Shakti Sanghatana into a scripted narrative, while in Maid Servant, Tobacco Embers, and Sudesha, Yugantar’s embedded process produced more dynamic braids of fiction and documentary.

The latter three films are all framed by staged sequences and first-person voice-overs that relate common narratives composited from diverse experiences—driving home how factory workers are at the mercy of sexually predatory bosses, or how deforestation drives men into the city, burdening women with the responsibilities of the entire household. These dramatic enactments are woven through with documentary footage from union, campaign, and protest meetings, where women share life details and deliberate on political decisions. Such sororal scenes of forum—of women gathering, debating, and storytelling—are the hallmark of Dhanraj’s films. They drive home a crucial thrust of her and Yugantar’s work: the conviction that feminist solidarity lies not in any essential qualities binding all women together, but in alliances forged across differences. Where the dramatized aspects of the Yugantar films collate individual experiences into a collective “I” or “we,” the nonfiction parts document the process through which that political alchemy happens.

Contractor’s camera roves kinetically through an array of faces in these sequences, as if buoyed by the heat of the discussion. The cinematographer would later shoot Mani Kaul’s rapturous Duvidha, filming the dust-swept landscapes of rural India with both extraordinary precision and a sense of earthy poetry. The Yugantar films employ a similarly loose yet structured lyricism but are shot through with the pulsating immediacy of documentary. Often positioned at eye level, Contractor’s lens captures both the speakers and the listeners—the call and the response—as the conversation ricochets between questions of labor, family, and home, accumulating a thrumming archive of working-class women’s lived experiences. These sequences are never punctuated by resolutions; Tobacco Embers ends smack in the middle of a lively debate about ways to encourage more women to join a proposed strike, underlining that solidarity is an ongoing, always unfinished project.

The sense of witness conjured by the Yugantar films—the feeling of watching history unfold in real time—has less, however, to do with any formal affectations than with the filmmakers’ commitment to entering the fray. Their presence is unseen but felt, the camera an extension of their bodies: a fist in the air rather than a fly on the wall. In Dhanraj’s first feature as a solo director, What Happened to This City?, that in medias res quality feels combustible, hot to the touch. An investigation into the Hindu-Muslim riots that exploded in Dhanraj’s hometown, Hyderabad, in 1984, the project began as a collaboration between the director, Contractor, and the activist Keshav Rao Jadhav. Jadhav had founded the activist collective Hyderabad Ekta to address communal tensions through secular dialogue and civil interventions, and he hoped that a film might be a useful “conversation starter.” When Dhanraj and Contractor began shooting, after two months of research, a fresh wave of riots erupted right in front of their eyes, triggered by electoral squabbles. They suddenly became reporters, pushing their camera right up against the glistening faces of demagogic politicians (both Hindu and Muslim) firing up crowds, and peering from roofs at bloodied streets patrolled by policemen enforcing curfews.