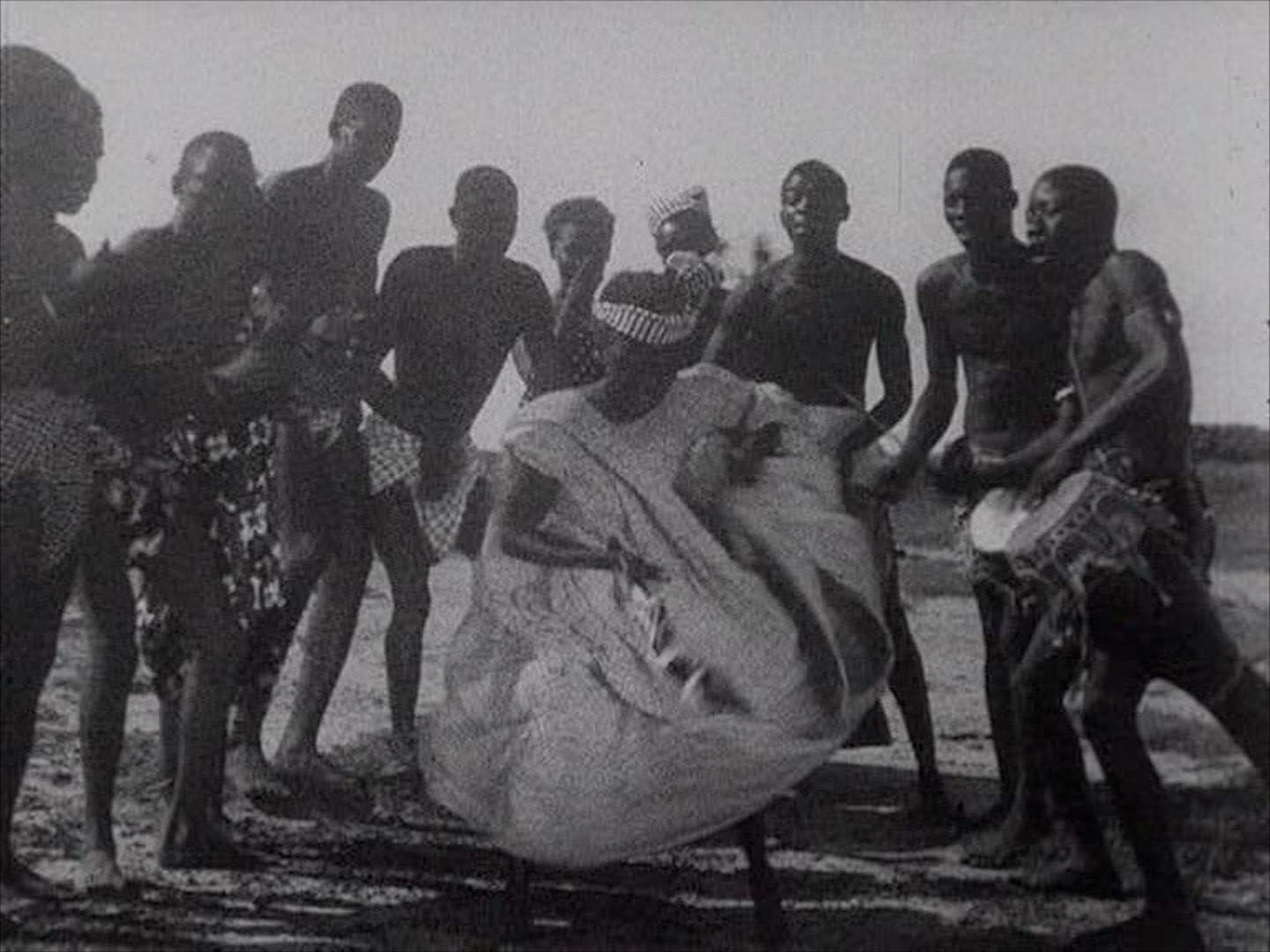

In all of Vieyra’s major films, the soundtrack is an integral aspect of the storytelling: evocative, sensuous, and capable of orienting a given narrative in a direction that may not be clear from its visual aspects. Halfway into Africa on the Seine, the pace slows down for a two-minute sequence of pure whistling and guitar, remarkable for leading to the appearance of a young woman waiting, smiling at the camera. She is Marpessa Dawn, later the star of Marcel Camus’s Black Orpheus. Similarly, in Môl (1966), about the efforts of a young fisherman adapting to changing technology, there is a ninety-second sequence of near-total silence, with rowing and environmental noises coming to the fore of the soundtrack. This is when the fishermen are out at sea, and the drudgery, if that, is sublimated into the gestures of work. The wrestling sequences in Lamb provide another good example. The combats unfold in multiple places—on sand, on grass—that are linked by montage to the spectators’ stands. However, the viewer is made to enjoy them as a single event through cuts that create a near-seamless progression of activities. The film’s single soundtrack is sustained throughout, without modulation or change, reinforcing the focus that drives the sport.

Perhaps the most extraordinary twist in Vieyra’s destiny is the fact that, though sent from home to school at age ten, and to a society as self-assured as France, he grew into a confidently Africa-centered intellectual. His job in Senegal might have had something to do with his success in weaning himself off Eurocentric affectations, if he had any, because he was in the service of a government that had set itself the mission of creating a new African culture. His attitude is reflected in Iba N’Diaye (1983), a portrait of the eponymous Senegalese artist, a modernist from a social background similar to Vieyra’s own, and the first director of Senegal’s National Fine Arts Academy. N’Diaye comes across as reverential of European masters, but he clearly sets his priorities on depicting African realities.

The questions that preoccupied pioneers of African filmmaking such as Vieyra and his close collaborators revolved around how to express the complexities of the continent’s cultures without denying the personal dimensions of their French education. Tunisian director Férid Boughedir captured this dilemma when he said that African cinema exists because and in spite of France. Sembène resolved the issue by refusing to prioritize European perspectives or needs, while also developing a Marxist critique of postindependence politics. The question of language was key for him as well: cinema enabled him to reach a nonreading public, and beginning with Mandabi he moved away from French in favor of noncolonial languages.

By the time Vieyra settled into his various roles in Senegal, the Laval Decree was a dead letter, and the orientation of his work was decidedly African. He had misgivings about the impact of Africa on the Seine, arising mainly from the fact that it was codirected and did not represent a single vision. But the interest in cultural self-retrieval in that work stayed with him, becoming stronger as he found wider institutional and artistic horizons. He was just as sensitive as his peers to the question of representation, constantly worrying about how to get African films out, make African directors known, and provide cultural education to young filmmakers. It is likely that he took on writing and producing mostly to fill these needs. The variety of roles he played in the nascent film industry suited him for the conference circuit and the boardroom, the domains of brokering and deal-making, and certainly made him less combative than the mercurial Sembène. (Recent biographical details have shown even the latter to be a pragmatist in real life: “I would sleep with the devil in order to make my films,” he says in the documentary Sembene!) Vieyra did not speak another African language after losing his Yoruba, so French was all he had. Nonetheless, these limitations did not affect the clarity of his artistic vision, which was unquestionably African.

The insistence with which Vieyra poses questions to Birago Diop and Iba N’Diaye in his filmed portraits of them seems to reveal a process of self-questioning. Like him, these men were products of the French educational system, that is, prime candidates for cultural assimilation into French life. But they returned to the continent to undertake work—fiction, painting—that depict African realities from the inside.

Vieyra used cinema to a similar end. As he declared in his book on the cinema in Senegal, “I would like to offer, first and foremost, an African point of view.” As far back as 1975, he had made a case for the collective term “African cinema” to describe the continent’s emerging film tradition. His reason at the time was that the cinema industries in African countries were not strong enough on their own to withstand discrete treatments. The term has remained timeless and serviceable, and reinforces a vision of cultural solidarity that most people now take for granted. In his compositional style, his approach to a variety of subjects through an easy mix of the investigative and the declarative, and his resourceful use of montage, he clearly inaugurated a directorial approach that other African filmmakers have appropriated. As Vieyra’s films, now restored and available to stream, become increasingly visible, the scholarship on African cinema will be richer and more sophisticated.

All images courtesy PSV Films