The Horror Gem That Kicks Off Three Cases of Murder

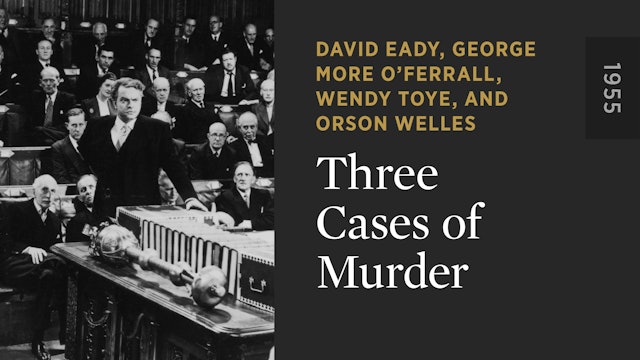

Because he’s Orson Welles, even during a less-bankable stretch of his career, he received top billing in Three Cases of Murder. Welles was also pictured most prominently on all the promotional materials for this little-known 1955 British anthology film, though he features in only one of the three episodes. It’s Alan Badel, appearing in all the stories, who is the star of the show. And his most memorable moments are found in Wendy Toye’s astounding kick-off, “In the Picture,” a mini-masterwork of fantastical horror.

In this segment, Badel plays a dapper, devilish-looking man whom we find in a museum scrutinizing a mysterious painting. The brooding, oddly compelling piece of art, depicting a desolate, doom-laden Gothic manor house, is labeled just “Landscape (Artist Unknown),” but after the man breaks its protective glass—not the first time, we learn—we begin to suspect he just may know something of its origins. Clearly more invested in the work than a mere aficionado, he interrogates a tour guide who deems the painting a masterpiece and suddenly conceives of a small adjustment that would change its composition for the better. And this is where the film, already hinting at the otherworldly, comes completely unbound from reality. The enigmatic patron hypnotically talks the guide (and us) into walking slowly toward the painting and down the long, fog-enshrouded path leading to the house’s door . . . until the two men have physically entered the painting.

Inside, a cozy, art-filled domestic space is introduced. The man who has invited us into his home, as he calls it, at first appears to live happily in the company of a welcoming female companion. But the unsettling skewed angles of the camera work quickly suggest the true nature of the sinister goings-on there (this is not a spoiler, given the film’s title). Under Toye’s expert direction, the action set within the painting’s interior is enthralling enough to have filled an entire movie. And the sequence’s genuinely chilling conclusion leaves you wanting more from the story and the director.

Toye, one of the first recognized female filmmakers to hail from the UK, was foremost a dancer—she choreographed a ballet at age ten—and a theater director, whose many productions included an acclaimed 1950 adaptation of Peter Pan on Broadway (starring Boris Karloff and Jean Arthur!). She moved into film directing in her midthirties, making a handful of beloved shorts, including The Stranger Left No Card, an enchanting mystery starring Badel, which won the Prix du Film de Fiction at the 1953 Cannes Film Festival, and On the Twelfth Day . . ., nominated for an Oscar in 1955. Following Dorothy Arzner, who directed a sequence in the big-studio revue Paramount on Parade in 1930, Toye is only the second woman to receive credit in an anthology film. (Irma von Cube wasn’t given official billing for directing a segment in 1951’s A Tale of Five Women; even more dismaying, all five parts of a 1953 Italian film called We, the Women were made by men). And this is an imbalance that persists—and not, of course, just in anthology films (though in 2017, a group of women banded together in revolt to write and direct the horror anthology XX, unfortunately a misfire).