John Huston, Freudian

Writer-director John Huston blasted the fusty pieties that pervaded big-studio filmmaking in the post-Code era, whether as the progenitor of film noir with The Maltese Falcon (1941) or the brainy daredevil who threaded critiques of frontier capitalism, gold lust, and lone-wolf mentality into the adult western The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). He captured the speed and thump of vital colloquial prose and the fortifying realism of tough-minded Depression-era novelists. The hard-boiled core of Huston’s legacy jibes with his persona as a globe-trotting man of action whose roistering spirit and grit enlivened urban capers like The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and outdoor films as varied as The African Queen (1951), Moby Dick (1956), and The Man Who Would Be King (1975).

But as Anjelica Huston notes in her introduction to the 2019 NYRB Classics edition of Lillian Ross’s Picture, any attempt to pigeonhole her father “as a hedonist, a womanizer, a man’s man, a sportsman, a gambler, a practical joker, a drinker, and an adventurer” misses “an essential point.” He was, she declares, “all these things and more. He was an artist.” And as an artist in the eclectic medium of the movies, he was aesthetically omnivorous: a voluptuary stylist (Moulin Rouge, 1952), a satirist (Beat the Devil, 1953), a genre master (The List of Adrian Messenger, 1963), an epic-maker (The Bible, 1966), an existential comedian (Prizzi’s Honor, 1985), and a lover of “high literature” (The Dead, 1987).

He was also—intermittently—a Freudian. Even before he started directing his own scripts, he regarded Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, as a prime candidate for a biopic. He considered writing a heroic account along the lines of Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940), the film about the man who found a remedy for syphilis that earned Huston the first of his eight Oscar nominations for best screenplay. Huston’s interest and enthusiasm intensified after he filmed psychiatrists treating traumatized World War II vets for his documentary Let There Be Light (1946). He compared watching Army shrinks hasten their patients’ recovery to a “religious experience.” A dozen years later he commissioned a script from Jean-Paul Sartre to dramatize the evolution of Freud’s thoughts and practices. Huston struggled with the length of Sartre’s screenplay—and the French philosopher ultimately removed his name from it—but Freud (1962) emerged as a seminal accomplishment and an enriching influence on Huston’s subsequent work.

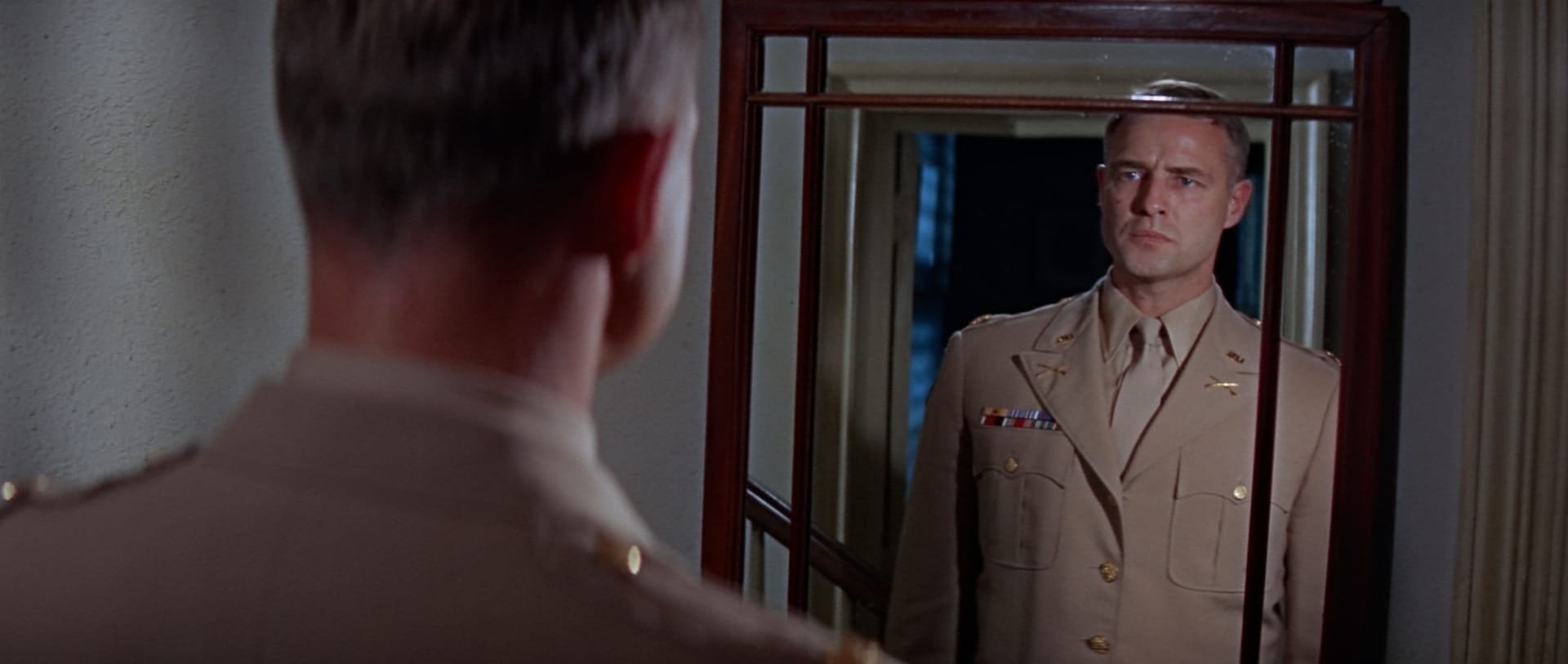

By the time Huston made his controversial adaptation of Carson McCullers’s Freud-infused Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), nothing human was alien to him, and his instincts had become super-refined. Huston never “psychologized” with his actors about their characters’ motivations, but he strove to maintain a psychoanalytic objectivity toward their drives and impulses and pipe dreams. With Reflections he was ready to go full shrink. He often averted his eyes from the action on the set to concentrate better on what the actors said. Marlon Brando approved: “He’s out in the background. He listens. He can tell by the tone of your voice whether you’re cracking or not.”